Council on Environmental Quality

Att: Edward Boling, Assistant Director of NEPA

Via portal only@ www.regulations.gov

Dear Mr. Boling:

The above Organizations welcome the opportunity provided in this comment period on how to refine and streamline the NEPA planning process and CEQ process to develop a more efficient and effective management process. After reviewing each of the 20 specific questions that were provided in the Federal Register notice on a variety of issues around the Endangered Species Act planning process and related topics, the Organizations above would answer each question in the affirmative.

The Organizations additionally would like to comment on two significant barriers to the efficient implementation of NEPA on public lands:

- Executive orders addressing travel management are simply out of date and require extensive re-analysis of issues resolved under planning requirements subsequently passed by Congress;

- Wilderness inventory processes in planning is cumbersome and redundant as planner often re-inventory areas Congress has specifically determined stated are not available for Wilderness designation and often directly contravenes the determinations in areas where multiple agencies have reviewed areas and determined them to be unsuitable.

The Organizations would also like to thank the CEQ for undertaking this review, as often planning documents and concepts are put in place and never reviewed again for basic relevance and meaning after the passage of time. Often this failure to review NEPA requirements results in repetition and confusion in the NEPA process that often generates only minimal on the ground benefits. It is not the Organizations intent to provide a complete list of these challenges but rather to highlight two of the more repetitive and confusing issues that are involved in the NEPA process..

1. Who we are.

Prior to addressing the specific concerns, our Organizations have regarding the NEPA process to date and streamlining of the process moving forward, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands.

Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport.

The Off-Road Business Association (“ORBA”) is a national not-for-profit trade association of motorized off-road related businesses formed to promote and preserve off-road recreation in an environmentally responsible manner and appreciates the opportunity to provide comments on this issue.

The Idaho Recreation Council (“IRC”) is a recognized, statewide collaboration of Idaho recreation enthusiasts and others that will identify and work together on recreation issues in cooperation with land managers, legislators and the public to ensure a positive future for responsible outdoor recreation access for everyone, now and into the future.

One Voice is a non-profit national association committed to promoting the rights of motorized enthusiasts and improving advocacy in keeping public and private lands open for responsible recreation through strong leadership, advocacy, and collaboration. One Voice provides a unified voice for motorized recreation through a national platform that represents the diverse off-highway vehicle (OHV) community. For purposes of this correspondence TPA, COHVCO, CSA, ORBA, IRC and One Voice will be referred to as “The Organizations”.

Collectively the Organizations have been actively involved in easily thousands of NEPA actions throughout the Western United States over their more than 30 years of existence with US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Dept. of Defense, and Bureau of Reclamation ranging from the recent landscape level forest plan amendments involving Sage Grouse and previous efforts on the Canadian Lynx to planning efforts involving management plans on a particular Forest or Field Office to small level planning efforts involving only a small portion of a field Office or Ranger District.

2. Landscape Concerns.

The CEQ has asked a series of general questions in the Federal Register notice on this issue and the Organizations would answer each of these questions in the affirmative. While we have not included a detailed response to each of the particular questions identified in the Federal Register notice, the Organizations have provided a full copy of the comments previously submitted with regard to the USFS planning revision process, commonly identified as the EADM process, and our comments submitted relative to the Western Governors Association efforts targeting Species Conservation and Endangered Species Act Reform. The Organizations have been active participants in these processes and are aware there is a significant amount of overlap between these efforts and the current proposal from the CEQ. The Organizations hope that by providing more detailed information and input on our experiences with the NEPA process on a wide range of public lands issues in the hope that previous mistakes will not be repeated and that this information will allow the CEQ to develop a Proposal that addresses challenges in the most effective and cost-efficient way possible.

The Organizations are providing these more extensive comments as we are aware that often the “why” behind a position that is taken is as important as the position itself. In these comments, the Organizations are targeting changes that can be undertaken in the planning process under the current legislative systems. While the Organizations support changes to the Legislative structure that governs planning, such as revising and updating the Endangered Species Act, the Organizations are also aware that such changes are outside the scope of the request from your Office.

3a. Maintenance backlogs, partner resources and NEPA.

The Organizations are intimately aware of the challenges faced on Federal public lands in terms of limited maintenance budgets and barriers to the effective use of partnerships to address maintenance issues as a result of the administrative barriers that in place as part of the current NEPA review process. While many in the recreational community are asserting volunteers are sufficient to address the maintenance backlog, this position fails to recognize that many maintenance issues simply cannot be solved with some hoes and shovels, regardless of how well intentioned any volunteer group maybe. Any effort at the levels necessary to address these levels of backlogs require funding and equipment, which the motorized community has provided for decades through their OHV registration programs. Often these funds are not fully utilized or matched due to land management budgets being directed to administrative inefficiency and the need to reconfirm decisions that have already been made. Resolving these inefficiencies would allow more funding to be available for basic maintenance and for the more effective engagement of partners on the ground.

These inefficiencies can result from the lack of clarity around Executive Orders and existing planning requirements in efforts to implement forest level planning obligations in subsequent site specific NEPA efforts. This lack of clarity in the decision making process often results from planners being forced to reopen decisions in site specific planning that were already resolved in landscape level NEPA to insure that conflicts and confusion in planning requirements are resolved. As President Trump accurately summarized in EO 13807:

“The poor condition of America’s infrastructure has been estimated to cost a typical American household thousands of dollars each year. Inefficiencies in current infrastructure project decisions, including management of environmental reviews and permit decisions or authorizations, have delayed infrastructure investments, increased project costs, and blocked the American people from enjoying improved infrastructure that would benefit our economy, society, and environment.”1

The confusion and conflict from overlapping or conflicting planning obligations is a major barrier to the effective use of partner resources to address infrastructure issues on public lands. The Organizations are aware that federal funding for maintenance of infrastructures on public lands is limited but partner resources are significant as the voluntary registration programs in many states more than double the amount of funding available to land managers for maintenance and operations. The voluntary registration programs adopted by the OHV community have created exceptional state partners for the management of federal lands The California OHV registration program has now contributed more than $500 million in partner funding to land managers2, and the Colorado motorized registration program is approaching $100 million in funding for land managers3. while these programs are highlighted in these comments, they are no means an anomaly as most western states have developed highly effective voluntary registration programs which institutionalize partnering with the federal lands managers. The motorized community is highly vested in resolution of these issues and is intimately aware of the barriers to effective management and full utilization of existing resources that are presented by the often repetitive or conflicting NEPA requirements for resolution of recreational infrastructure projects on the ground.

3b. Economic benefits of recreation limited by NEPA.

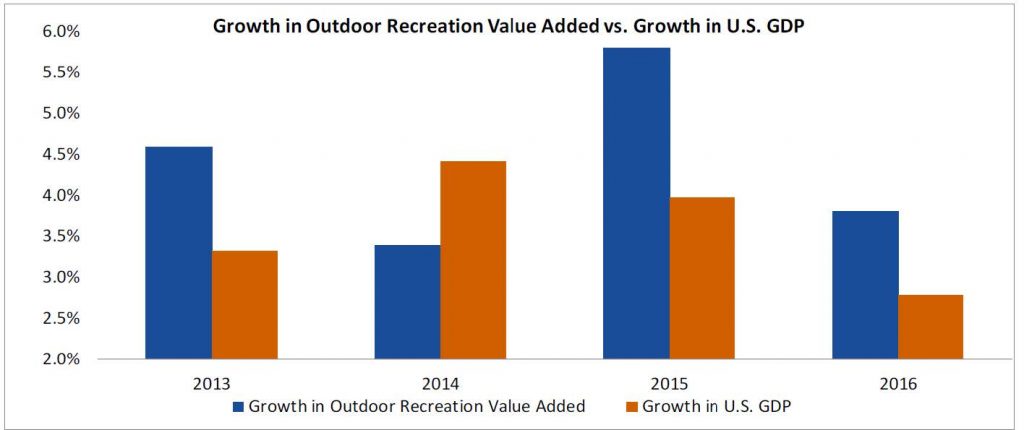

As President Trump also accurately identified, recreational activities on federal lands is also a major economic driver for local communities. The Department of Commerce recently concluded that recreational spending contributed more than 2% of the Gross Domestic product and was growing faster than the Gross Domestic Product as follows4:

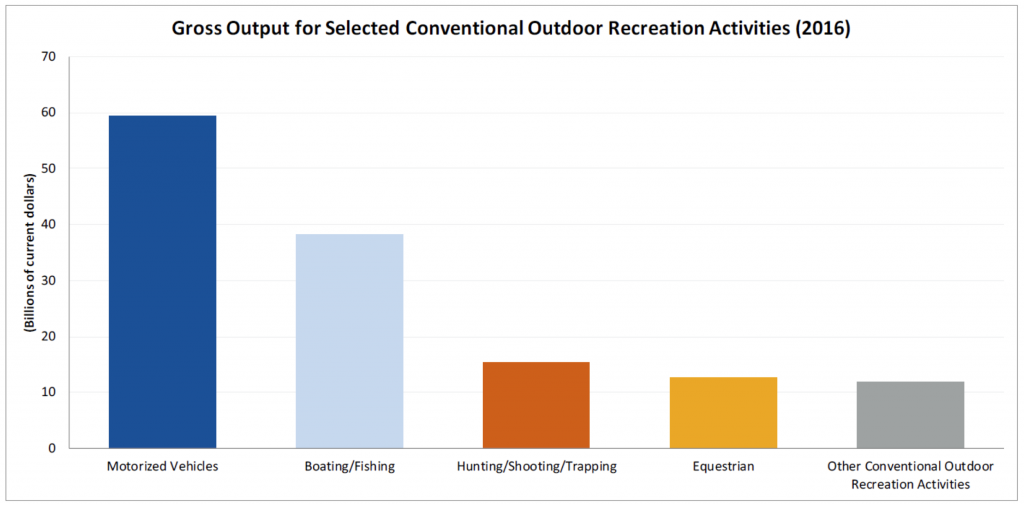

The Department of Commerce further concluded that the overwhelming portion of this economic benefit flows from motorized access and usage. The Department of Commerce conclusions on this were stark as follows:

Motorized Vehicles was the largest activity within conventional outdoor recreation in 2016, accounting for $59.4 billion of gross output. Recreational vehicles accounted for more than half of this value at $30billion.

Many state level research efforts have targeted this question with more detail, such as the 2012 Economic Contribution study from the State of Colorado, which concluded this activity contributed more than $2.3 billion in spending to the state economy and most of this was centered in small communities that are now overly reliant on recreational activity for basic sustainability of the community. A copy of this study is enclosed with these comments.

Documentation is major barrier despite USFS desire to expand usage of partners and volunteers and passage of the National Forest System Trails Stewardship act by Congress in 2016. In these comments, the Organizations are not attempting to provide an exhaustive list of the challenges that are faced by the voluntary registration programs in their partnerships with land managers but rather identify major systemic challenges that consistently reduce the effectiveness of current monies on the ground.

4. Executive Orders regarding travel management are simply out of date and are a major barrier to effective infrastructure investment.

As noted previously, the Organizations have participated in thousands of NEPA actions throughout the Western United States over the last 40 years and one of the most consistent barriers to effectively managing issues on the landscape is the Executive Orders governing what has become known as the Travel Management Orders and Rule. The original Travel Management Order was issues by President Richard Nixon in 1972 (EO 11644) and was only substantively updated by President Carter in 1977(EO 11989). Planning agencies have updated internal requirements around travel management but even most recent of those was 2005. The fact that the Travel Management Orders were issued almost 50 years ago and have not been meaningfully reviewed speaks volumes to the need for this type of review to insure basic relevance of these orders to issues on the ground.

While the age of these Orders alone would pose a minimal issue, the age becomes more problematic when subsequent Congressional actions regarding management of public lands is integrated into the planning process. Congress enacted FLPMA in 1976 which has guided the management of public lands since its enactment and required identification of goals and objectives for particular areas on public lands, including the density or intensity of development allowed inn particular planning designations. As a result of the FPLMA planning process, the travel orders are almost entirely redundant with FLPMA requirements. As federal land managers are now moving forward with updating the first round of landscape level management plans created under FLPMA, the conflict and confusion between FLPMA processes and the TO is becoming more of an issue. Planners are unsure if these are separate planning goals, can be combined and often over-plan and analyze as a result in the hope of avoiding litigation on decisions being brought. Significant public pressure from those opposed to the general principal of multiple use is applied and seeks to determine that existing forest planning and minimization criteria are entirely separate planning requirements and that minimization must be done at every step of the planning process.5

The age and overlap of these Orders results in a large amount of conflict and confusion in the planning process over time and artificial elevation of travel management to levels of priority that simply are not warranted on the ground. This artificial elevation of travel management would be exemplified by planning to address trails on a forest or ranger district where tree mortality has exceeded 90%. There can be no rational argument that planning for roads and trails should be a higher priority in this situation but often pressure is applied to move forward with minimization of impacts from roads and trails. In addition to the hot bed of litigation against the agencies, the lack of clarity in the planning process results in efforts that are taken to address issues impacting resources due to flooding or fires are often delayed for years in the NEPA process. Rather than moving forward with funding that might be available almost immediately, federal land managers are forced to enter into lengthy NEPA planning efforts in order to explain the decision being made.

Additionally there are concepts in these Executive Orders that are older than every forest plans created in the first rounds of planning under FLPMA. Everyone agrees those forest plans are comically out of date and badly in need of updating, and similar concerns could be raised about the age of the Executive Orders addressing travel management. The age and overlap of these orders is often a hot bed for litigation challenging the end result of any NEPA process as often the redundancy of these orders and FLPMA making full documentation a long and drawn out process that has minimal impacts or benefits on the ground. Often these Executive Orders introduce concerns into the NEPA process that are entirely redundant with planning requirements that are now required by Federal Management requirements under FLPMA and other planning requirements. Minimization criteria in these Executive Orders would be one example of the redundancy that has resulted from these orders not being updated to reflect actions by Congress subsequent to the issuance of these orders, such as FLPMA.

Additional redundancy of planning and the minimization criteria required under the Executive Orders results from the diversity of paths taken by land managers in complying with these requirements. Some forests addressed minimization at the landscape level and developed forest level travel maps that were often unrelated to conditions on the ground, while other forests addressed with site specific planning efforts on an as needed basis. Each of these issues present separate and unique challenges in planning but both are impacted by the high levels of employee turnover within federal agencies and often poor retention of planning records. While challenges are often brought against both processes, site specific planning also allows litigation against the overall process by groups that participated in the original site specific planning and failed to raise any concerns about compliance with landscape level planning requirements at the local level. These issues are compounded by the fact that managers are now having to manage documents that were created almost 40 years ago. Documentation of decisions was complied with an entirely different levels 50 years ago simply due to the evolution of technology.

Further delay in management and maintenance of public lands results from the Executive Orders results from the fact that minimization of impacts is often a major concern in subsequent smaller scale planning to advance usage in areas that might be identified as high usage areas in existing forest level planning. This confusion is despite the fact that minimization has already occurred at the Forest level and the area has been identified for high levels of usage.

The conflict and confusion between the Executive Orders, which are now badly in need of updating and FLPMA is compounded by the fact that many forests are now moving to update forest level planning document under FLPMA. With these efforts, there is now significant pressure being applied for managers to start from scratch on minimization questions, even when there is a solid paper trail in place to explain the process to date on the forest. When managers are not able to document minimization, that pressure is increased as would be exemplified on the recent litigation surrounding the Pike/San Isabel (“PSI”) National Forest in Colorado. The PSI was sued in 2010 and that litigation was settled in 2016 due to the fact managers could not document the organization of their site specific travel planning process. As a result, a forest level travel plan was to be developed and the minimization criteria have become a major hurdle in that process, which alone raises concern on the conflict due to the fact that the PSI forest plan was completed almost a decade after the issuance of the Executive Orders and passage of FLPMA. There can be no rational argument made that the forest plan did not comply with these requirements, but since managers are not able to justify the decisions made more than 3 decades ago, planning is again brought to the forefront.

The PSI litigation and subsequent settlement provides for another opportunity for redundant and burdensome planning requirements as the PSI is planning to update their Forest plan immediately after the issuance of the Forest level travel decision. As part of the development of the second Forest Plan, the minimization criteria must again be addressed due to forest management goals objectives changing. Essentially the PSI will have to comply with the minimization criteria in the Executive Orders, create a forest plan and re-minimize under the new forest plan criteria. This is the pinnacle of redundant and ineffective governmental process as decades of planning efforts, millions in resources which will improve not single acre of land on the forest or the growing maintenance backlog of facilities on the forest.

A second example of how the Executive Orders age and redundancy are resulting in a horribly inefficient utilization of resources and delaying improvement of conditions on the ground is provided in the recent elevation of the entire winter travel management process for over the snow vehicles (“OSV”) travel. This would be another example of where the travel management orders could be refined and updated in order to obtain significant new efficiency in the NEPA process. Despite recent court actions, winter travel management has already occurred on overwhelming portion of forests with snow and again the planning process was highly divergent on forests throughout the country as some forests never got snow, others only received snow on a small portion of the forest while others received significant snow across the forest. While there was not a national policy or other national action, the diversity of planning made a lot of sense on the ground due the highly variable nature of weather and snowfall. Many forests effectively engaged a diverse range of interests and concerns in the development of snowmobile plans for areas and these areas have been effectively managed for many decades. The successful and effective management of OSV issues is again an issues as much of this planning occurred several decades ago and most decision makers have retired and documentation has been lost. The conflict and confusion of existing planning under FLPMA and the Executive Orders is again coming to the forefront.

The conflict between the Executive Orders, FLPMA and the age of forest plans has resulted in widespread litigation of existing snowmobile planning, as demonstrated by recent litigation against several forests in California around their winter grooming programs, the challenge to the entire winter planning process brought in Idaho courts and subsequent challenges to forests that have moved forward under the terms of the settlement agreements. Now planners are being forced to return to an issue most offices thought were settled and defend decisions that have been effectively managing issues for decades as a result of litigation being brought. The conflict and confusion between the Executive Orders and forest planning requirements has resulted in land managers poorly defending winter travel decisions. Winter travel is an issue that was resolved under FLPMA planning without objection from those now challenging these decisions many decades later, but must be re-reviewed to insure impacts have been minimized as required under Executive Orders. Conflict between FLPMA planning and the Executive Orders is again raised as a major planning concern by those seeking to restrict usage and public access to infrastructure.6

The Organizations encounter the conflict and confusion that results from the conflict between the outdated Executive Orders and existing FLPMA planning which has complied with NEPA on an almost daily basis. This conflict and confusion slows the effective engagement of partners to improve recreational infrastructure on public lands and reduces economic benefits to local communities, both of which were clearly identified in President Trump’s EO 13807.

Possible resolutions of Travel Management Rule issues:

- Update out of date Executive Orders targeting travel management;

- Provide presumption that minimization in second round of forest planning is complied with unless can be proven otherwise;

5. Wilderness inventory process and WSA management provide areas where significant efficiency is now available.

A second area where significant efficiency gains could be achieved is through the re-review and updating of conflicting management guidance the inventory and planning for future Wilderness designations in the FLPMA/NEPA planning process. Many of the concepts that are identified in the Wilderness Act for the inventory of public lands are simply out of date and again result in numerous extra steps in the planning and analysis process. While much of this inventory process is mandated under the Wilderness Act, there is extensive efficiency gains that could be achieved in the second round of NEPA planning under FLPMA by limiting the scope of review to areas that are available for designation and currently managed for such an objective. Managers should also be made aware of the fact that the mere inventory of areas for Wilderness suitability often makes any subsequent management of the area for multiple use more complex.

When the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, there was simply very limited data even available regarding the characteristics of undeveloped tracts of federal land. Over the next 50 years, undeveloped lands under federal management have been the basis for extensive federal analysis and discussion and hundreds of thousands of public lands have been protected by Congressional action. While extensive tracts of land were designated as Wilderness, extensive other areas were consistently identified as unsuitable for designation in the inventory process and a smaller portion were released by Congress from the need for further review. While extensive areas have never been suitable for designation, managers are forced to re-inventory these areas in each planning process.

Given this extensive inventory and subsequent Congressional action that has occurred since passage of the Wilderness Act, there can be no factually based assertion there are large areas to be inventoried for possible Wilderness for the first time, as there is a finite number of acres of public lands and these have been repeatedly inventoried and addressed by Congress. The possibility of finding new lands that might be suitable for Wilderness designation is minimal at best. While the probability of finding new Wilderness is very limited, land managers are often forced to re-inventory areas found unsuitable previously or areas that have been specifically released by Congress or are hesitant to rely on previous determinations excluding an area from designation due to a particular usage even when that usage is still present in the areas being inventoried.

While there is minimal chance of finding new Wilderness areas for designation in second rounds of planning, there is no process to recognize the repeated inventory of lands and Congressional action in new rounds of planning or NEPA analysis. Without this type of a presumption, land managers are often forced to fully review areas that have never been suitable. Managers must also inventory lands released back to multiple use as part of previous Congressional actions, simply because of the requirement that citizen Wilderness petitions are specifically identified as a planning element in the inventory process. Often these citizen petitions fail to recognize previous Congressional action releasing areas or protecting multiple usage and garner little support from the public in the Legislative process. Despite these facial failures to establish a valid planning issue, land managers are forced to address these citizen petitions. Clarifying that areas not managed for Wilderness are probably not suitable for future designation would significantly streamline planning and NEPA analysis and allow for the more efficient management of federal lands.

An examples of the administrative burdens and inefficiency that result from the repetitive nature of the Wilderness inventory process is exemplified by management history of significant acres on the GMUG and San Juan national forest. Significant portions of the forest were found unsuitable in RARE 1&2 processes, unsuitable in Primitive Area analysis by Bureau of Mines and were released by Congress after highly site specific analysis and discussion with diverse interests in Wilderness legislation due to high levels of recreational activity in these areas. Land managers are still forced to address these areas for possible Wilderness designation in the future due to citizen inventories and legislative proposals that have been introduced since previous Congressional determinations on the areas. Land managers feel compelled to re-inventory these areas despite the fact that legislative proposals expanding these designations have never moved forward in the legislative process despite being introduced for decades and the clear Congressional action releasing the area from future Wilderness inventory.

The inefficiencies and barriers to utilization of these areas is presented by the ongoing Wilderness inventory process involving the North Sand Hills area outside Walden Colorado. This area provides a unique recreational opportunity that local, state and federal managers would like to expand and improve. This expansion and improvement is functionally prohibited by the fact that the area was inventoried as a WSA due to existing primitive area designation when the Wilderness Act was passed. Development is functionally prohibited despite the area being found unsuitable in original rounds of inventory. Motorized access to sand dune type riding exceptionally limited in Rocky Mountains and the opportunities provided in the North Sand Hills is probably unique in the Nation in the fact that users can ride sand dunes in the morning and then connect to extensive trail network in Rocky Mountains in the afternoon. Currently rustic camping and minimal services are provided on North Sand Hills. Everyone would like to expand these opportunities to improved camping facilities and integrated trail network to provide a solid economic driver for local communities. This expansion which has been supported by wide range of interests including Wilderness Society and other conservation groups. While this area has been the basis of specific WSA release legislation that legislation has not moved due to the exceptionally small size of the area. 7 The barrier to management and utilization of this area due the lingering WSA designation functionally prohibits expansion and utilization of the area due the possible designation of the area as Wilderness.

These lingering inventory and designation issues are not isolated to a small number of sites, but rather impact a large number of acres of public lands and result in other challenges that limit the effective and efficient utilization of these lands for the benefit of local communities. The ongoing inventory requirements lead to conclusions that are simply beyond rational description being made in the land management process as exemplified by the management of the West Needles WSA outside Durango, CO. This area was identified as a WSA in the 1980 Colorado Wilderness Act8 and subsequently inventoried in 1982, where a large portion was suitable for designation and a small portion was found unsuitable due to high levels of usage in that area. This recommendation was moved forward in 1993 Colorado Wilderness designations and the WSA designation was repealed.9 Despite this repeal of the WSA designation, the WSA designation remained in place due to the inventory of the area once and these existing usages were again put at risk in 2012 when land managers sought to close these usages due to the previous inventory. This issue was finally resolved when Congress again sought to release the area with the designation of the area as an SMA for motorized usage, which was passed into law in 2014.10 While the issue was legislatively resolved, the inefficiency and limitation on utilization of the area is immediately apparent.

These issues are not limited to Colorado as similar challenges have been encountered in Idaho, where certain Roadless areas were specifically identified as areas where access is to be expanded in previous Congressional action but continue to be inventoried or managed for Wilderness. In the 1980 Idaho Wilderness Act, use of numerous backcountry airstrips was specifically excluded and protected11, but despite these protections, land managers have continued to have to manage these airstrips as if they were impairing Wilderness. This process has again complicated maintenance of these areas and limited the economic benefit from these areas.

Possible resolutions of Wilderness inventory issue:

- Provide presumption that areas previously found unsuitable or released have not become suitable merely due to the passage of time

6. Conclusion

The above Organizations welcome the opportunity provided in this comment period on how to refine and streamline the NEPA planning process and CEQ process to develop a more efficient and effective management process. After reviewing each of the 20 specific questions that were provided in the Federal Register notice on a variety of issues around the Endangered Species Act planning process and related topics, the Organizations above would answer each question in the affirmative.

The Organizations additionally would like to comment on two significant barriers to the efficient implementation of NEPA on public lands:

- Executive orders addressing travel management are simply out of date and require extensive re-analysis of issues resolved under planning requirements subsequently passed by Congress;

- Wilderness inventory processes in planning is cumbersome and redundant as planner often re-inventory areas Congress has specifically determined stated are not available for Wilderness designation and often directly contravenes the determinations in areas where multiple agencies have reviewed areas and determined them to be unsuitable.

The Organizations would also like to thank the CEQ for undertaking this review, as often planning documents and concepts are put in place and never reviewed again for basic relevance and meaning after the passage of time. Often this failure to review NEPA requirements results in repetition and confusion in the NEPA process that often generates only minimal on the ground benefits. It is not the Organizations intent to provide a complete list of these challenges but rather to highlight two of the more repetitive and confusing issues that are involved in the NEPA process.

If you have questions please feel free to contact either Scott Jones, Esq. at 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont, CO 80504. His phone is 518-281-5810 and his email is scott.jones46@yahoo.com or Fred Wiley, ORBA’s Executive Director at 1701 Westwind Drive #108, Bakersfield, CA. Mr. Wiley phone is 661-323-1464 and his email is fwiley@orba.biz .

Respectfully Submitted,

Scott Jones, Esq.

COHVCO & IRC Authorized Representative;

CSA President

Fred Wiley, ORBA President and CEO;

Authorized Representative of One Voice

Don Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

CC: Vickie Christiansen, Chief USFS

1 Executive Order 13807 of August 15, 2017 Establishing Discipline and Accountability in the Environmental Review and Permitting Process for Infrastructure Projects Federal Register Vol. 82, No. 163 Thursday, August 24, 2017

2 For more information on the California program please see: http://ohv.parks.ca.gov/

3 For more information on the Colorado OHV/OSV programs please see: http://cpw.state.co.us/aboutus/Pages/TrailsGrantsOHV.aspx

4 A complete copy of this research is available here: https://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/industry/orsa/orsanewsrelease.htm

5 This documentation is exemplified by the following document: https://wilderness.org/sites/default/files/ORV%20Minimization%20Criteria%20White%20Paper—May%202016.pdf

6 This conflict is again exemplified by the following guidance documents from those opposing multiple usage: https://winterwildlands.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/BMP-Final.pdf

7 See, HR 5570 of 114 Congress.

8 See, PL 96-150 §105(a)(9)

9 See, PL 103-77 §4a

10 See, PL 113-291 §3062

11 See, PL 94-951 §7a.