BLM Colorado State Office

Attn: Big Game RMPA/EIS

2850 Youngfield Street

Lakewood, CO 80215

RE: BIG GAME HABITAT AND MIGRATION CORRIDOR AMENDMENT

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the input of the Organizations with regard to possible amendments of existing RMP for Big Game Habitat and Migration Corridor Amendment (“The Proposal”). Prior to addressing the specific concerns, the Organizations have regarding the Proposal, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization of approximately 250,000 registered OHV users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations. The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a largely volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands. Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite the more than 30,000 winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport. CORE is an entirely volunteer nonprofit motorized action group out of Buena Vista Colorado. Our mission is to keep trails open for all users to enjoy. For purposes of these comments, TPA, CSA, CORE and COHVCO will be referred to as “the Organizations”.

The Organizations participated in the public meetings that were provided by the BLM on this issue and were surprised to hear a FAR more broad scope of the project than is currently provided for. Our experiences with the Sage Grouse management efforts have allowed us to understand that anytime route density standards are addressed, such as in the Proposal, there will be recreational impacts due to route closures. This is a situation where one size fits all management is totally inappropriate and significant amounts of work must be performed on existing data to understand the myriad of site-specific issues that species are facing in the state and what previous management challenges have been faced in these areas. While the state of Colorado may have requested this review, it does not absolve the BLM of basing management decisions on best available science.

The Organizations are very concerned that a significant amount of foundational analysis for the effort does not appear to have occurred and if it has occurred it has not been discussed. The Organizations submit this spans many facets of the Proposal, which ranges from questions like has there been a decline in wildlife populations in Colorado? Is there a single factor causing the perceived decline in wildlife populations? If so, how was this determined. What was the time frame for this conclusion and analysis? How was the relationship between an asserted decline in populations been attributed to a lack of habitat? These are foundational questions that must be addressed before any range of alternatives is even formulated, as our minimal research indicates there are a huge number of factors impacting wildlife populations, ranging from the window of time used to analyze declines or increases, poor data being available for analysis and other management efforts driving down populations based on best available science. Once these other factors are addressed the Organizations vigorously assert the relationship between populations and habitat declines must be established. This simply has not been done to date. If the BLM is going to move forward with any analysis of options as required by NEPA, these are foundational questions that must be addressed.

1(a) The 50-year history of the BLM managing motorized recreation to protect wildlife resources.

The Organizations are concerned that the current Proposal has a very wide scope of analysis in terms of challenges and issues and the broad scope of the documentation was greatly expanded in the public meetings that we participated in. This is very concerning for us, especially when there is insufficient analysis of possible impacts to existing resources from the management process currently under analysis. Prior to addressing the unusual scope of analysis for the Proposal, the Organizations would like the opportunity to provide input on the decades of effort that have gone into minimizing possible impacts from motorized recreation on wildlife. The motorized recreational community has been directly managed by the BLM for more than 50 years for the minimization of impacts to a wide range of other activities including wildlife.

The management of motorized recreation on federal public lands started in 1972 with the issuance of Executive Order 11644 by President Richard Nixon, which clearly states as follows:

“Those regulations shall direct that the designation of such areas and trails will be based upon the protection of the resources of the public lands, promotion of the safety of all users of those lands, and minimization of conflicts among the various uses of those lands. The regulations shall further require that the designation of such areas and trails shall be in accordance with the following–

(1) Areas and trails shall be located to minimize damage to soil, watershed, vegetation, or other resources of the public lands.

(2) Areas and trails shall be located to minimize harassment of wildlife or significant disruption of wildlife habitats.

(3) Areas and trails shall be located to minimize conflicts between off-road vehicle use and other existing or proposed recreational uses of the same or neighboring public lands, and to ensure the compatibility of such uses with existing conditions in populated areas, taking into account noise and other factors.

(4) Areas and trails shall not be located in officially designated Wilderness Areas or Primitive Areas. Areas and trails shall be located in areas of the National Park system, Natural Areas, or National Wildlife Refuges and Game Ranges only if the respective agency head determines that off-road vehicle use in such locations will not adversely affect their natural, aesthetic, or scenic values.”[1]

This management has taken many forms over the subsequent decades and in many places 3 or more travel management plans have been undertaken in order to balance motorized recreation with possible impacts to resources and wildlife. Issues such as route density and other issues that might be impacting wildlife, such as the need for seasonal closures and wildlife corridors, have been the basis of numerous site-specific concerns in Travel plan development for almost 50 years.

The Organizations have also had an MOU signed with the State BLM office for decades to ensure that our efforts are aligned as closely as possible on a wide range of issues. A copy of the most recent agreement on the accomplishments of this effort are attached as Exhibit “1”. No other recreational activity is involved with these types of issues than the motorized community and we would like to avoid possible impacts to these efforts that could result from unintended impacts of efforts.

1b. Resources the motorized community provides to benefit wildlife and recreation.

As we noted above, the motorized community has a unique relationship with the BLM beyond the additional management requirements of EO 11644. The motorized community as also created a voluntary registration program for the OHV community that returns almost all funding back to land managers for the maintenance of opportunities.[2] The management of motorized usage is significantly $8 million per year provides more than 60 dedicated maintenance crews for the benefit of summer and winter recreation and resource protection. This program has been administered with CPW for more that 30 years, and has now exceeded $100 million in on the ground funding to land managers.

Through this program, each BLM Field Office have dedicated maintenance crews for each office that are able to target wildlife management actions, such as opening and closing gates, education of users and other on the ground management needs that protect wildlife values and resources and improve recreational access to the area as well. These maintenance crew grants are currently funded at $85,000 per year per planning area and several BLM planning areas are working with multiple crews in an area. To supplement these efforts, each field office also is able to apply for additional resources on an as needed basis including targeted law enforcement resources and extensive Youth Corp resources to help with larger challenges on the FO such as wildfire and flooding issues that can be highly destructive to wildlife resources as well.[3] These structured OHV crews in the Field Offices also have access to the Statewide Heavy maintenance crew based out of Grand Lake to further improve responses to a wide range of issues on the ground. The OHV program has also provided more than 2 dozen skid steer loaders, mini-excavators and trail dozers to further improve maintenance capability on public lands. All these resources protect wildlife and wildlife habitat while improving recreational opportunities.

As an example of the scale of resources available as a result of the OHV grant program, CPW estimates that wildlife signage should cost between $2,000 and $3,000 per year to maintain.[4] The OHV program provided $130,000 in grant funding for signage last year that is divided across each management unit in the state.[5]

This program is a resource that no other nonconsumptive recreation interest provides and these resources simply alter the playing field when discussing resource protection and wildlife management issues. Many groups are willing to address management standards but are unable to provide any resources to carry out these requirements and it is possible that those issues may fall in management priorities over time and as a result decline in effectiveness. With directed consistent funding this does not happen with motorized recreational interests.

1c. How will BLM multiple use mandate and existing designations be protected in the Proposal?

The Organizations are very concerned about possible impacts to the decisions that have already been made under the multiple use mandates of the BLM. Often these area designations are striking a balance of uses across the FO or planning area. The Proposal would be looking at these designations in isolation, as the scope of the Proposal is only addressing wildlife corridors, which would only impact a small portion of the planning area. The Organizations would ask for clarification on how multiple uses of the entire field office is maintained if there is a change in a designation in the RMP already in place. For example, if there was a dedicated or protected use in the RMP that must now be altered or limited where would this use be moved to on the FO? How was this decision made outside the wildlife habitats simply must be explained. This type of decision making is critical to transparency and maintaining the multiple use mandate that was previously balanced in the RMP planning process.

2a. Wildlife populations in the State are stable, generally at or above objectives and in many cases improving already.

The Organizations vigorously assert that credible peer reviewed published information must be relied on for the analysis of conclusions that are foundational to the development of the Proposal. It is becoming far too common that we are seeing assertions that wildlife populations are in massive decline in Colorado due to a lack of habitat. We are simply unsure what this information is based upon as it appears to be horribly inaccurate. Given that the long-term population treads for species in Colorado as improving since the early 1980s, we must also assume that habitat is in reasonably good shape given the trend has persisted for more than 40 years.

It has become far too common at the state level to hear unsupported allegations that wildlife populations have plummeted. It is interesting and highly frustrating to us CPW research that has been published concludes that numerous species are generally populations are at or above objectives and are well above total populations of the species in 1980. In some localized areas there have been declines in wildlife populations in limited geographic areas due to management actions by CPW for that species. Most commonly this has resulted in the increased numbers of hunting tags being sold in these areas to mitigate overpopulations of wildlife in the areas. Sometimes these efforts have sought to manage impacts to a wide range of other resources or species to reductions in populations to address issues like chronic wasting disease impacts.

In many areas where these types of reductions have occurred, many other species have significantly increased at the same time. This situation would lead to the conclusion that declines are not habitat based but rather are based on a social desire to have multiple species on the landscape rather than a large number of a single species. It is highly frustrating for the recreational community when planning in based on inaccurate or incomplete information about an issue or fails to represent social considerations such as these. Colorado is in the midst of yet another reallocation of wildlife on the landscape after Proposition 114 was passed that mandated the reintroduction of wolves in Colorado. The Organizations would believe it to be naive to assume this will not alter the current populations of species on the Colorado landscape. Management actions are scientifically based and opposition to previous management decisions should not be driving future management decisions, especially when the interests driving this discussion have not participated in these efforts previously. No matter how much habitat is provided, there is always a limit to the carrying capacity and without management it can be exceeded. Wanting a larger number of species on the landscape will reduce the number of species that can occur on the landscape, simply due to natural factors such as interspecies competition.

CPW issued the 2020 Status Report on Big Game Winter Range and Migration Corridors (Hereinafter referred to as the “Winter Range Report”) in response to many of the same guidance documents, such as Secretarial Order 3362 and others, that are now asserted to be driving the current proposal. A complete copy of this report is attached as Exhibit “2” to these comments. This report made many findings that are highly relevant to these efforts by BLM as there is significant conflict between the positions taken in this Proposal and those published by CPW in 2020. The elk population was summarized as follows:

“The statewide 2018 post-hunt population range is 233,000-282,000. The 2018 post hunt estimate was 287,000, up slightly from 282,000 in 2017 (Figure 5). CPW utilizes season structure and hunter harvest, specifically antlerless harvest, to maintain or achieve population herd objectives. CPW has intentionally reduced elk populations to achieve population objectives. Reductions in antlerless licenses are anticipated as elk populations reach objectives or as population objectives increase.

Hunters and outfitters have increasingly expressed concerns that elk populations are becoming too low in some herds, despite the fact that 22 of 42 (52%) of the elk herds are above their current population objective ranges”

While we do not contest that hunters may like to increase their odds of a successful hunt, this is also not a shortage of habitat for elk. This is a social desire expressed by almost every user group. The Organizations would note that almost every recreational group would like to see expanded opportunity to achieve their recreational goals and as a result we must question the value of the closing assertion in the report.

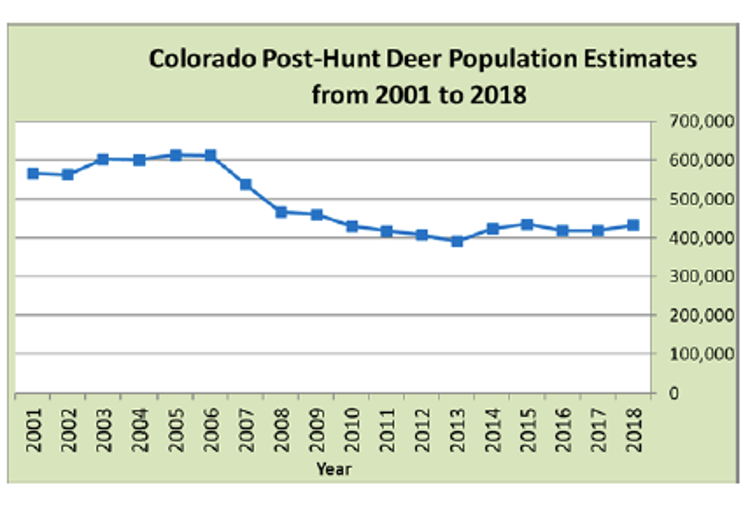

Deer have a more variable trend in populations based on a larger number of factors impacting these species such as winter kill, drought and wasting disease, but generally these populations appear to be reasonably steady, which the Winter Range Report outlines as follows:

The winter range report specifically attributed this population situation to a wide range of factors as follows:

“The product of this public process was the 2014 West Slope Mule Deer Strategy (WSMDS). The WSMDS identifies seven management priorities to address mule deer declines on the West Slope of Colorado.

-

- Landscape-scale habitat management to improve habitat quality

- Predator management where predation may be limiting deer survival

- Protection of habitat and mitigation of development impacts

- Reducing the impacts of highways on mule deer survival, movements and migration

- Reducing the impacts of human recreation on mule deer

- Regulation of doe harvest and providing youth hunting opportunity

- Maintaining a strong big game population and disease monitoring program and conducting applied research to improve management of deer populations”

Given this clear and concise statement from CPW as to their landscape level threats to deer, the Organizations would believe any assertion that habitat alone is causing the decline in the population would lack factual and legal defensibility.

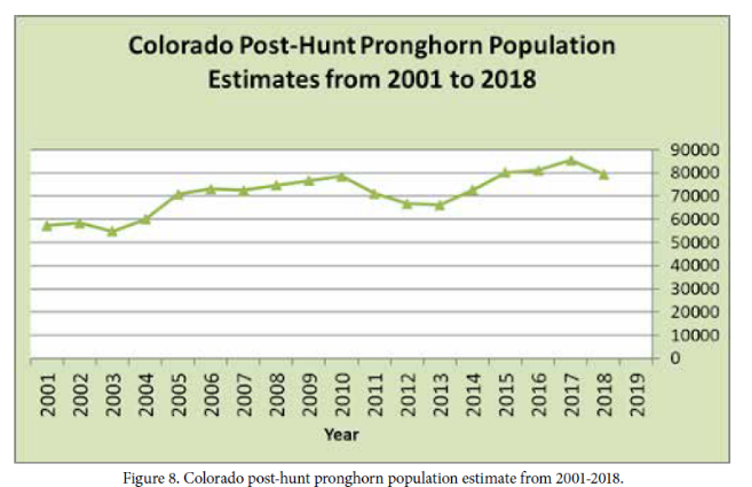

A strong steady increase in the state population of pronghorn is also identified. Similar stability in the long-term population of pronghorn has also been identified by CPW as follows:

Given that the total number of pronghorns in the State is about 2,000 more animals than were present in 1980 or a 30% increase in pronghorn populations since 1980, we would argue this is a huge success of management efforts by everyone, and this should be celebrated as huge win for the species rather than a need for more restrictions and analysis of habitat.

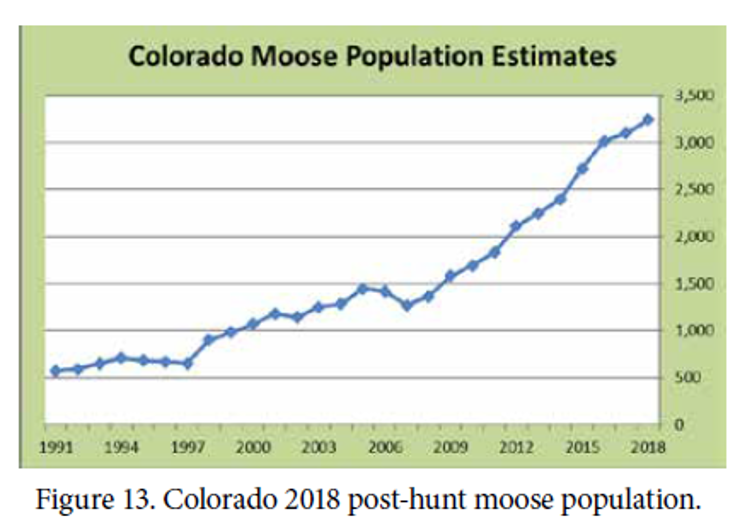

CPW conclusions for moose populations in the state are simply amazing as there are 7 times more moose in the state when compared to 1991. This is the result of CPW efforts around the large-scale reintroduction of this species in the mid-2000s in several locations in the state. This trend is represented in the CPW Winter Range report as follows:

Given that the total number of moose in the State us 7 times more animals than were present in 1991, we would argue this is a huge success of management efforts by everyone, and this should be celebrated as huge win for the species rather than a need for more restrictions and analysis of habitat.

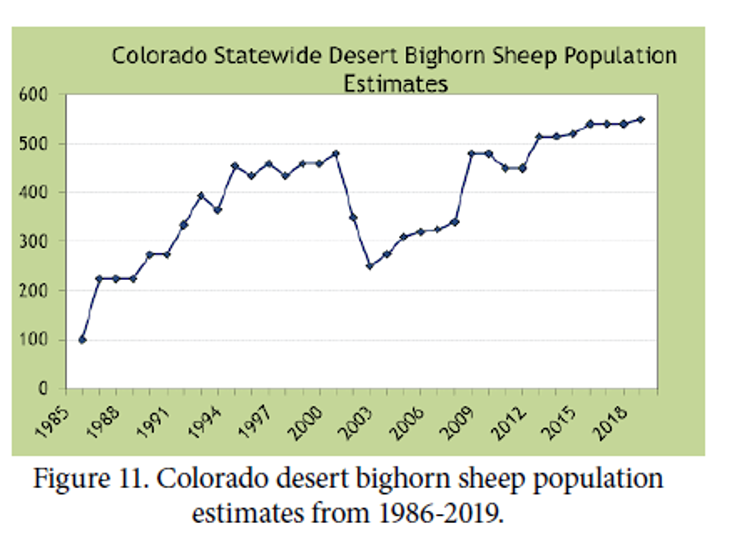

CPW has also been very active in reintroducing big horn sheep. The population reintroductions undertaken are outlined in the CPW Big Horn Sheep plan as follows:

“One reason for the apparent increase in Colorado’s bighorn populations is a longstanding effort to trap and translocate wild sheep to establish new populations or supplement existing populations. From 1945–2007, there were 47 releases of bighorn sheep in Colorado resulting in the translocation of 2,424 animals (excluding bighorns moved to research facilities). The majority of these transplants occurred during the 1980s. In 2007, translocated herds accounted for 54% of the total herds in Colorado and 48% of the total statewide bighorn population. Most transplant herds (78%) had less than 100 sheep in 2007 and relatively few of these herds have shown the sustained growth needed for long-term viability. Extant herds that have been supplemented with translocated sheep accounted for 24% of the total herds and 30% of the total statewide bighorn population in 2007.”[6]

As a result of these reintroductions, similar trends are found in sheep populations as Sheep are 6 times the population in 1985 which is represented in the Winter Range Report as follows:

Given that the total number of moose in the State is 6 times more animals than were present in 1991, we would argue this is a huge success of management efforts by everyone, and this should be celebrated as huge win for the species rather than a need for more restrictions and analysis of habitat.

While not mentioned in the Winter Range Report, the Organizations are also aware that CPW has undertaken a highly successful reintroduction of Canadian Lynx in the state, which is now above the target population for that species as well. CPW has also undertaken the reintroduction of dozens of species of fish, black footed ferrets, boral toads and simply too many other species to even list. We don’t contest that some species may be declining in limited areas but given that CPW has published and peer reviewed information that the deer and elk populations in the state are reasonably close to goals for the species we must question the basis for the assertion that these populations are collapsing or declining. Best available science indicates exactly the opposite is the case.

We must also assume that habitat is sufficient to support the species, and this assumption is compounded by the huge number of other species that have been successfully reintroduced into the Colorado ecosystem over the last 50 years. A huge number of these species’ reintroductions have been the subject of NEPA analysis, if there are assertions that NEPA analysis of some projects that might impact wildlife populations must be reviewed then the Organizations assert that all NEPA analysis must be reviewed, not just a select few. If The Organizations must also vigorously assert that Colorado has a demonstrated track record of wanting more diversity of species on the landscape rather than larger number of limited species. In the face of this type of influx of so many species on the landscape, and assertion that habitat is problematic for the future of wildlife in the state is going to be difficult.

2(a)(2). How are low quality data and management issues in herd management addressed before management changes are found to be necessary in the Proposal?

The Organizations do not contest that deer and elk populations may have appeared to decline at the state level but the mere perceived decline in two populations is not a basis for management decision making before data and local issues are specifically addressed in the planning process. Basic data analysis is critical to ensuring that an accurate representation of population trends is obtained and not influenced by local impacts or issues that are isolated in time. This concern is compounded by the exponential growth of so many other species over the same timeframe. While the Organizations are aware that the current effort has been undertaken at the request of the State of Colorado, this does not absolve BLM from ensuring that basic scientific processes are used to address the management situation. This type of management analysis must be undertaken prior to any management changes being undertaken on any portion of BLM managed lands. It is our position that this type of decision making is highly social in nature and represents a reasoned social decision at the state level that more diversity of species is desired by the public than large numbers of a single species. This desire of Colorado residents to have more diversity of species on the landscape could not be more perfectly reflected than by the recent passage of Proposition 114 which mandated the reintroduction of gray wolves in Colorado. Colorado has also reintroduced dozens of other species onto the landscape with generally huge levels of success. These are factors that also must be included in analysis if there are restrictions for usages of habitat being explored. Even without the desired intent of the state of Colorado to have more species diversity, the management decisions must address the myriad of site-specific issues and challenges that have been addressed on these areas and understanding this management history is critical as sometimes these trends are the result of management actions.

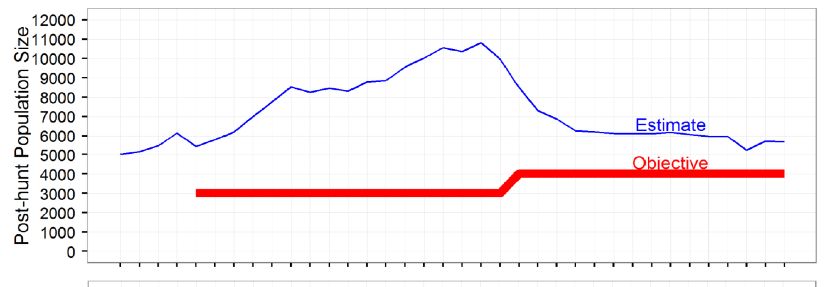

The following examples are raised as an example of the more localized issues that must be addressed in any landscape effort and they were identified after only a few minutes of research. This list is by no means complete or exhaustive, but merely represents the type of problems frequently encountered that can heavily impact any attempt to address issues like this at the landscape level. Other locations have been plagued by a myriad of other issues, such as poor historical count data for a species. These are issues that can only be addressed at the local level and are simply poorly suited to landscape level management given the huge number of issues that are faced. An example of a large decline in population that was completely unrelated to BLM management or habitat would be provided by the E25 Unit. The E25 elk unit had decades of unchecked elk population increase that CPW determined had to be managed around 2000. The basis and analysis for this decision making is laid out in multiple herd management plans from CPW. The 2017 CPW herd plan for unit E25 has shown this graphically as follows:

This management action in this area alone accounts for more than 5,000 less elk in the state and can almost entirely account for the decline in population in state population estimates. Without context this trend would be alarming, but context adds a huge amount of understanding to the discussion. When context is provided for the decline in population, the Organizations submit this area is a huge management WIN that must be celebrated rather than further restrictions. This is an area that had a minimal population of elk, which was managed and exploded. As a result of the explosion of population managers miscalculated the necessary management to correct the explosion. This is a good problem to have rather than a calamity to be managed. The 1999 E25 herd plan provides this context as follows:

“All stakeholders agree the elk population in the DAU has been relatively stable and significant reductions have not occurred over the past 10 years. New population models indicate that the population has continued to increase in recent years. Public land management personnel are concerned about the health of range resources. Most agree that some reduction is necessary, but there is some disagreement on how much reduction should occur. This disagreement is mostly focused around the current population estimate, which some stakeholders believe is too high.” [7]

The management history in the area is further addressed in the 1999 herd plan as follows:

“Number of limited antler-less licenses has been sharply increased over the past several years, but harvest rates haven’t been sufficient to start decreasing the population.” [8]

These types of management decisions are only addressed briefly in the 2017 herd plan but are hugely related to the decline of the elk populations in the area. [9] The 1999 CPW E25 report further outlines additional history in the management area as follows:

“During spring and summer 1998, the DOW lost two court cases. The group opposing the over-the-counter either-sex elk licenses in GMUs 54, 55 and 551 won their case. The DOW asked the Wildlife Commission to approve antler-less licenses for the fall hunt. The group opposed to the limitations in GMUs 66 and 67 won their case and the two units were once again open to unlimited, over-the-counter bull licenses.” [10]

The need for a complete understanding of local context and factors surrounding issues like this is critical to avoiding conclusions that simply make no sense. As an example, while the E25 unit elk population was being hunted down as a result of a significant increase in license sales implemented in the early 2000’s, the BLM was also closing more than 46% of roads and trails in the area through the Gunnison Basin Travel Management Plan. [11] While there was an additional decline in this population around 2012 the comical lack of relationship between the two efforts could not be more stark, as clearly route density declined as did herd populations. This type of situation presents an interesting question. Mainly how was the relationship of route density and wildlife populations established as this unit appears to identify the exact opposite situation. In situations such as this a lack of context can lead to comically incorrect management assumptions as in Unit E25 the assertion could be made that closing trails caused a population decline in elk. While we know this is not the case, these types of horribly incorrect assertions can be made if local information and issues are not addressed. This type of basic analysis must be undertaken to ensure management is actually addressing the challenges actually faced in the area.

These types of exceptionally localized problems exist on a myriad of other units that clearly impact population trends. This is exemplified by the E13 1999 plan specifically outlines the exceptionally poor nature of their historical data as follows:

“The current objectives for this DAU were set in 1990, and it now appears that the population size was underestimated by at least 30% at that time.” [12]

This means that population estimates were off by more than 1,500 elk on this unit alone and this type of error could significantly impact any statewide population goals when statewide populations are only 2,000 animals below state level goals. This situation is not even mentioned in the more recent E13 management plan but could clearly create the appearance that populations have significantly changed in the area. These are the type of changes that can NEVER be fixed with land management decisions but rather can only be fixed by getting accurate data. These are the types of data issues are critical to the analysis that must occur in this effort prior to any management alternatives even being undertaken.

2(a)(3). The comical conflict of positions of several Organizations on the wildlife population sizes must be addressed.

The Organizations believe the unprecedented nature of this and several other efforts in Colorado has forced some wildlife advocacy organizations into some enormously conflicting positions on issues. Some of these conflicts could not be more direct in nature on materially factual issues, and these conflicts are occurring within days of each position being taken. The Organizations are concerned that this situation creates the appearance of groups approaching this effort in less than good faith. This gives us pause and concern and as a result vigorously asking for extensive analysis for all recreational access given the lack of good faith that has been displayed by groups to this point. We have no expectation that good faith efforts will suddenly return to these discussions at some point in the future, but these Organizations will simply continue to display bad faith in the process moving forward and we simply cannot envision where is process may be directed as a result.

An example of the conflicting positions on factually identical questions is exemplified by the WildEarth Guardians assertion that the State of Colorado has too many elk and deer and the reintroduction will return balance in populations to the State as a part of their citizen reintroduction proposal submitted to the CPW Commission in July of 2022.[13] This is astonishing inconsistent with the general position of WildEarth Guardians, exemplified by the fact WildEarth Guardians is suing the Rio Grande NF asserting the RMP revision did not adequately protect declining populations from possible recreational impacts as filed in November of 2021.[14] In almost every other effort than the wolf reintroduction we have consistently been told that ungulate populations are on the edge of the cliff of catastrophic decline. These are positions that simply cannot be reconciled and give us concerns about the possibility of unintended consequences of management.

We believe that the current litigation ongoing on the Rio Grande over species and populations is a concrete example of why we are asking for strict review of any data or trend data. The Organizations have been forced to intervene in the litigation of the Rio Grande in defense of claims with the US Forest Service, in Order to provide support, knowledge and resources in the litigation. While we will continue to fight for access, we would also like to think that at some point this type of conflict might come to an end. While the above example is provided in isolation, we are sure other concerns will be taking unusual positions compared to the historical positions and management to be undertaken. As a result of what could clearly be a lack of good faith by certain interests in the process on basic factual positions, the Organizations would again ask that scrutiny be provided as broadly in scope as possible to protect all recreational access in the efforts subsequent to this. We have no expectation that good faith efforts will return to the wildlife management discussion in the State at any point in the foreseeable future.

2(b)(1) Are BLM efforts the best method to address general wildlife populations?

As we have noted throughout these comments, the State of Colorado has demonstrated a long history of wanting greater species diversity in the state rather than larger populations of a single species. We are also aware that the most direct population reduction effort for species in hunting and in many areas, there have been planned scientifically based reductions in wildlife through significant increases in hunting licenses. Given that the effort has the goal of increasing wildlife habitat and populations, we must question how this is achieved. Improving habitat will not increase populations but rather without coordination will only increase the sales of hunting licenses and result in a population that remains at objectives.

This type of hugely conflicted situation that can result from socially based decision-making gives rise to a unique and problematic foundational concern, which the Organizations believe also must be corrected in the NEPA analysis that is being proposed. This situation is basically summarized as every user group on the landscape believing that they have minimal impacts and blaming other users instead of accepting responsibility for their actions. Researchers have summarized this situation as follows:

“Approximately 50% of recreationists felt that recreation was not having a negative effect on wildlife. In general, survey respondents perceived that it was acceptable to approach wildlife more closely than our empirical data indicated wildlife would allow. Recreationists also tended to blame other user groups for stress to wildlife rather than holding themselves responsible.”[15]

While the above process and analysis is addressing recreational activity, the Organizations simply cannot imagine how this type of issue would not be impacting efforts at the geographic scale that is being undertaken in the Proposal. BLM must attempt to correct for these types of issues in their planning efforts as well. The Organizations have to question how the current proposal has been identified as a management tool that can address the desire for larger wildlife populations. There are many other activities and tools that can drive wildlife populations upward far more quickly than restricting access to public lands.

2(b)(2) Hugely effective management efforts can occur without BLM involvement but result in massive increases in wildlife populations.

The Organizations are aware that wildlife management has taken new and exciting turns in Colorado in the last several years, such as the addition of wildlife overpasses on several interstates and state highways. These overpasses have resulted in huge increases in wildlife populations in areas that have had them in place long enough to document benefits. Once such benefit was documented by the Western Governors Association in conjunction with a wildlife overpass on US 89 outside Kanab Utah. This analysis immediately documented a huge benefit to a single species as follows:

“It is estimated that a minimum of 102 accidents will be prevented each year through this collaborative effort. Utah State University will study this project over the next five years to provide feedback to the partners on the effectiveness of their efforts and to provide information on how best to design solutions to similar problem areas for wildlife and motorists.”[16]

This type of benefit was not calculated for other species but we have to believe significant benefits were achieved for other species as well. Saving hundreds of deer per year is a huge benefit that simply is not even calculated on any units that have newly built wildlife overpasses in Colorado. The Organizations must question how these types of projects and benefits would be addressed in a project similar to the Proposal as BLM may not even be involved in these efforts. While BLM may not even be involved in the local effort, these local efforts could hugely impact species populations at the local and state level.

2(c) Secretarial Order 3362 has been addressed for recreational activity in Colorado.

The Organizations would note that Secretarial Order 3362, which does address wildlife and habitat is also asserted to be the basis of the current Proposal also recognizes and excludes from its application management goals that have already been addressed in previous planning efforts from further review. Interestingly, this would appear to preclude the inclusion of issue like possible changes in management conditions in the area and would force change in condition type concerns to be directed to the original planning effort rather than addressed in the current effort. These designations in place for recreational improvement and protections, such as SRMA and ERMA planning designations have been highly site specific in development and were placed to avoid high quality habitat areas and avoid seasonal challenges to wildlife from recreation. Since these designations have already been developed with these goals in mind, these designations are outside the scope of the Secretarial Order and must be protected from change without further detailed analysis. Expanding the scope of the current Proposal to address motorized recreational access would be problematic.

Secretarial Order 3362 specifies this type of an exclusion as follows:

“(2) Within 60 days, if this focus is not already included in respective land management plans, evaluate how land under each bureau’s management responsibility can contribute to State or other efforts to improve the quality and condition of priority big-game winter and migration corridor habitat.”[17]

Protecting wildlife populations and habitat has been a cornerstone of providing motorized recreational opportunities, has clearly been addressed in every RMP we are familiar with in the state. CPW has provided volumes of input into the development of these plans. Given the clear exclusion of previous management efforts to address the question of route density and site-specific issues throughout the state, the Organizations vigorously assert that existing designations of routes and trails is outside the scope of Secretarial Order 3362 and must be protected and preserved if this effort moves forward.

2(d) Habitat must be defined and consistently applied across each species being addressed in the Proposal.

The Organizations are concerned that the current purpose and need is not particularly well defined, and this type of basic definition will be critical to the success or failure of the project. Throughout the Proposal terms like “important habitat” or “high priority” habitat are used to outline the scope of the effort but these terms are never defined or outlined. As a result, the Organizations must ask questions such as: Important habitat as defined by who? What factors were used to identify the characteristics of that area make the habitat important must be addressed? How were areas found to have these characteristics and other areas not have these characteristics? How was importance of habitat balanced or addressed across the multiple species? How were local issues such as those previously raised in these comments corrected for in the determinations of the area’s importance for planning?

These are basic questions that simply must be addressed and this concern is heightened when the purpose and need for the project is identified. Purpose and need of project are identified as follows:

… the preliminary purpose of evaluating alternative management approaches for the BLM planning decisions to maintain, conserve, and protect big game corridors and other important big game habitat areas on BLM-managed public lands and minerals in Colorado. This action is needed to ensure that the BLM considers current big game population and habitat data, including maps of high priority habitat, and to evaluate management consistency with plans or policies and programs of other Federal agencies, State and local governments, and Tribes, to the extent consistent with Federal laws, regulations, policies and programs applicable to public lands.

The inability of the species habitat to be accurately described and classified gives rise to a host of other problems in subsequent species management efforts, such as habitat identification or avoiding unintended management actions taken in the generalized habitat information already provided. Without a good description how do we not have problems with the 2018 US Supreme Court’s unanimous Weyerhaeuser. While the USFWS recently withdrew the proposed definition of habitat required by Weyerhaeuser, this does not mitigate the legal requirements of the Weyerhaeuser decision.

The Organizations are very concerned that the current documentation is highly theoretical in nature and far from a settled scientific model moving forward. The use of modeling in the ESA has been an issue that has been the basis of dozens of treatises and texts and is far from a resolved issue.[18] These reviews have consistently identified the need for the scientific community to provide legally sufficient basis for species management. This standard has been summarized as follows:

“Given the importance of maintaining biodiversity for both ethical and practical reasons- foe example to sustain environmental goods and services critical to human welfare (Hooper et al 2005)- it is imperative that the scientific community provide land managers with the knowledge and tools needed to meet their conservation mandate.”[19]

Other researchers have stated this standard in the management as listing of identifiable species, such as the Mexican gray wolf as follows:

“Policy-related uncertainty originated from contrasts in thresholds for acceptable risk and disagreement as to how to define endangered species recovery. Rather than turning to PVA to produce politically acceptable definitions of recovery that appear science-based, agencies should clarify the nexus between science and policy elements in their decision processes. The limitations we identify in endangered-species policy and how PVAs are conducted as part of recovery planning must be addressed if PVAs are to fulfill their potential to increase the odds of successful conservation outcomes.”[20]

These treatises also provide highly detailed discussions on the management of uncertainly in the assumptions and data in the species/habitat modeling process. Listing a species based on a lack of information on the species is a failure of basic scientific processes around the modeling of any habitat areas for a species. In habitat discussions, too often processes fail in correcting basic modeling errors, as is mandated by the scientific process for modeling any activity. Instead, these modeling errors which are not based on scientific process are sought to be normalized in a rushed effort to protect a species.

The Organizations vigorously assert that the problems with modeling the species that cannot be described or scientifically defined accurately are compounded when applications of habitat designation standards are undertaken. The challenge of modeling habitat is immense and only expanded when the species cannot be defined. Recent USFWS efforts have highlighted the habitat designation challenges for identifiable species as follows:

“In particular, the proposed definition is written so as to include unoccupied habitat, whereas many of the definitions in the ecological literature that we reviewed did not appear to consider unoccupied areas.”

The concern of the scientific community around management of poorly defined habitat is not minor. The mandate of applying best available science (“BAS”) is one of the cornerstones of the entire federal planning process and is specifically applicable to the designation of both basic habitat and critical habitat.

While the process for modeling of any activity has not been a hot bed of legislative activity, modeling of complex activities and relationships occurs consistently throughout the world on a huge number of issues and has been the basis of extensive scientific and scholarly analysis. While there are an exhaustive number of models for almost any activity, the Organizations are aware that all modeling guidelines require some basic review of the model to ensure the model is accurately predicting the behavior that is sought to be modeled. While no model is perfect in predicting all behavior, there needs to be some level of correlation between the model and the behavior modeled. If the model does not accurately forecast or provide consistent results, the model is fixed and management action is not taken. A good general summary of the modeling and simulation process is provided by Wikipedia.com, which provides the following general guidance on modeling of behaviors

“Modelling as a substitute for direct measurement and experimentation. Within modelling and simulation, a model is a task-driven, purposeful simplification and abstraction of a perception of reality, shaped by physical, legal, and cognitive constraints. It is task-driven, because a model is captured with a certain question or task in mind. Simplifications leave all the known and observed entities and their relation out that are not important for the task. Abstraction aggregates information that is important, but not needed in the same detail as the object of interest. Both activities, simplification and abstraction, are done purposefully. However, they are done based on a perception of reality. This perception is already a model in itself, as it comes with a physical constraint. There are also constraints on what we are able to legally observe with our current tools and methods, and cognitive constraints which limit what we are able to explain with our current theories.

Evaluating a model: A model is evaluated first and foremost by its consistency to empirical data; any model inconsistent with reproducible observations must be modified or rejected. One way to modify the model is by restricting the domain over which it is credited with having high validity. A case in point is Newtonian physics, which is highly useful except for the very small, the very fast, and the very massive phenomena of the universe. However, a fit to empirical data alone is not sufficient for a model to be accepted as valid. Other factors important in evaluating a model include:

-

- Ability to explain past observations

- Ability to predict future observations

- Cost of use, especially in combination with other models

- Refutability, enabling estimation of the degree of confidence in the model

- Simplicity, or even aesthetic appeal” [21]

As briefly outlined in the Wikipedia definition, the evaluation and revision of any modeling or simulation of behavior is a critical step in the modeling process and without success at this step the model should be modified or rejected entirely. This double check of the accuracy of the model to predict behavior is a basic review for any model of activity or behavior. While the list of modeling guidelines is overwhelming, recognition of the requirement for a double checking of the accuracy of the model under non statutory situations. For creation of a business model, Entrepreneur magazine recommends the following step in the development of a business model:

“2. Confirm that your product or service solves the problem. Once you have a prototype or alpha version, expose it to real customers to see if you get the same excitement and delight that you feel. Look for feedback on how to make it a better fit. If it doesn’t relieve the pain, or doesn’t work, no business model will save you.” [22]

A similar need to double check that any model is accurately reflecting the behavior sought to be modeled in the development of mathematical models. This requirement in mathematical modeling efforts is outlined by experts as follows:

“3. Determine how the model could be improved. In order to make your model useful for further applications, you need to consider how it could be improved. Are there any variables that you should have considered? Are there any restrictions that could be lifted? Try to find the best way to improve upon your model before you use it again. [8]“[23]

Similar to the modeling of business activities and mathematical theory, best available science on the modeling of wildlife habitat also has an exceptionally well-defined process for development of species or habitat models. This process includes a step to review that the results of the model are corresponding with the actual life activity of the species. This process of modeling wildlife habitat has been outlined as follows:

“Modeling wildlife habitat over this range of scales requires many assumptions about the relationships between wildlife population metrics and habitat occurrence, quality, and spatial distribution. Standard modeling protocol is to explicitly state all assumptions early in the process; substantiate those assumptions with field data, published information, or expert opinion; hypothesize the relationships among wildlife and their habitat; and use the modeling framework to evaluate sensitivities and produce output. One critical assumption underlying this protocol is that habitat is accurately characterized at ecologically relevant scales to the organism(s) of interest.” [24]

Other experts have provided the following summary of the wildlife habitat modeling process:

“The Process of model evaluation and validation is a critical step in modeling. However, this evaluation should not focus on how well the model captures “truth” (verification) but how well the model performs for its intended purpose.”[25]

Without exaggeration there are libraries full of scholarly materials addressing the proper methodology for the development of habitat models for wildlife, and these range from discussions at a very general level to the specific process that was used to model habitat for a species. This level of vigor in order to establish a defensible scientific model of habitat is often simply not present planning process but needs to be in the Proposal, as this is targeting habitat.

Even when addressing wildlife habitat, best available science clearly identifies the need to ensure modeling of habitat areas is actually reflecting the species and the areas the species depends upon for basic life activities. While best available science clearly requires if a model does not accurately reflect the modeled behavior, this is a basis for review and modification of the model and not moving forward with the recommended actions of the model. If the modeling accuracy cannot be improved to a scientifically defensible level, the modeling effort is stopped at some point. This simply is not how modeling of habitat has occurred in our experiences under planning process as often the rush to protect the species overwhelms any discussion of revision of models due to poor performance of the model in predicting behavior. The Proposal would be a good example of the relationship of these types of challenges in the management of a possible species.

The Organizations believe a comparison to the facts around the listing of the Gopher frog which was struck down in the recent Weyerhaeuser Supreme Court decision and the current proposal will clarify our concerns about the poor resolution of the management of uncertainty. The gopher frog listing provided the following criteria for habitat which are summarized as small ponds that hold reasonable quality water at least 195 days of the year, a lack of predatory fish; and an open canopy herbaceous forest. [26] The comically broad nature of these modeling factors is immediately apparent, as under these factors the gopher frog could be living in almost any pond in the country. It should be noted that these factors could be applied to a huge number of OTHER species totally unrelated to the gopher frog as well. Almost no pond in the country could be excluded with these modeling factors despite the fact the gopher frog has never lived in most of the country. This is an example of a failed habitat model, which could be corrected with a more detailed discussion of why the area is thought to be suitable.

3. User conflict can easily be created with overly broad route closures.

The Organizations believe that analysis of how best available science supports the management decisions and direction any proposal constitutes a critical part of the planning process, especially when addressing perceived user conflicts. This analysis will allow the public to understand the basis of alleged user conflicts and why travel management has been chosen to remedy the concern. Relevant social science has clearly found this analysis to be a critical tool in determining the proper methodology for managing and truly resolving user conflicts.

When socially based user conflict is properly addressed in the Proposal, the need for travel management closures will be significantly reduced. Researchers have specifically identified that properly determining the basis for or type of user conflict is critical to determining the proper method for managing this conflict. Scientific analysis defines the division of conflicts as follows:

“For interpersonal conflict to occur, the physical presence or behavior of an individual or a group of recreationists must interfere with the goals of another individual or group….Social values conflict, on the other hand, can occur between groups who do not share the same norms (Ruddell&Gramann, 1994) and/or values (Saremba& Gill, 1991), independent of the physical presence or actual contact between the groups……When the conflict stems from interpersonal conflict, zoning incompatible users into different locations of the resource is an effective strategy. When the source of conflict is differences in values, however, zoning is not likely to be very effective. In the Mt. Evans study (Vaske et al., 1995), for example, physically separating hunters from nonhunters did not resolve the conflict in social values expressed by the nonhunting group. Just knowing that people hunt in the area resulted in the perception of conflict. For these types of situations, efforts designed to educate and inform the different visiting publics about the reasons underlying management actions may be more effective in reducing conflict.”

Other researchers have distinguished types of user conflicts based on a goals interference distinction, described as follows:

“The travel management planning process did not directly assess the prevalence of on-site conflict between non-motorized groups accessing and using the yurts and adjacent motorized users…..The common definition of recreation conflict for an individual assumes that people recreate in order to achieve certain goals, and defines conflict as “goal interference attributed to another’s behavior” (Jacob & Schreyer, 1980, p. 369). Therefore, conflict as goal interference is not an objective state, but is an individual’s appraisal of past and future social contacts that influences either direct or indirect conflict. It is important to note that the absence of recreational goal attainment alone is insufficient to denote the presence of conflict. The perceived source of this goal interference must be identified as other individuals.”

It is significant to note that Mr. Norling’s study, cited above, was specifically created to determine why winter travel management closures had not resolved user conflicts for winter users of a group of yurts on the Wasache-Cache National Forest. As noted in Mr. Norling’s study, the travel management decisions addressing in the areas surrounding the yurts failed to distinguish why the conflict was occurring and this failure prevented the land managers from effectively resolving the conflict.

The Organizations believe that understanding why the travel management plan was unable to resolve socially based user conflicts on the Wasache-Cache National Forest is critical in the Colorado BLM planning area. Properly understanding the issue to be resolved will ensure that the same errors that occurred on the Wasache-Cache are not implemented again to address problems they simply cannot resolve. The Organizations believe that the Colorado BLM must learn from this failure and move forward with effective management rather than fall victim to the same mistakes again.

4. CPW’s Trails and wildlife guide must be standard for analysis of any impacts of Proposal on recreational areas or routes as this has been signed by the BLM.

The Organizations have partnered with CPW, USFS and BLM for the development and updating of the 2021 CPW Guide entitled “Colorado’s Guide to Planning Trails with Wildlife in Mind.” The Organizations along with more than a dozen state and local agencies, including the BLM and Forest Service spent more than a year of dedicated meetings to develop this Guide. Given that BLM signed this Guide and was seminal in the development of the document, we believe this document is highly relevant to the analysis of possible impacts of route density standards. A copy of this report is attached as Exhibit “5” to these comments. We are deeply disappointed that this document is currently not mentioned in the Proposal despite the numerous mentions of route densities as objectives of planning.

5. Executive Orders requiring an expansion of recreational opportunities issued by President Biden must be addressed in the Proposal.

The Organizations would note that the America the Beautiful and 30×30 efforts have been referenced in the scoping brochure, several times in Presentations in public meetings and was the topic of extensive discussion in various meetings around the initiative. We are very concerned that these were exceptionally generalized references and that these efforts are often poorly summarized in the discussions. The Organizations submit that how the Proposal relates to these efforts remains horribly unclear as no substantive National level guidance has been provided on the EO or related efforts, making any implementation efforts difficult to understand and achieve as the goals of these efforts remain unclear. These types of goals and clarity are highly relevant to states like Colorado who have actively moved federal public lands into various levels of either Congressional or administrative designations. The Organizations have been active participants in numerous efforts to Congressionally protect areas and would assert that generalized goals such as 30×30 have been achieved in Colorado, making any asserted basis for the effort lacking factual basis.

The recent issuance of Executive Order # 14008 by President Biden on January 27, 2021 would be an example of a decision that is often only partially summarized in most materials we are seeing submitted in comment processes for federal land planning, as the “30 by 30” concept is memorialized in this Order. It is our position that the 30 by 30 concept was long ago satisfied on the planning area given the large expansions either Congressionally designated Wilderness, or National monuments in the area over the last several decades. In direct contrast to the summaries of EO 14008 we are seeing, this Order had provisions protecting lands generally but also had specific goals of improving access to public lands. This have been overlooked in most summaries but the Organizations submit these requirements are critical to bringing balance to public lands. Before addressing the 5 times recreational improvement is specified in EO 14008, the Organizations must also recognize that wildlife and habitat concerns are only indirectly mentioned in the EO. While we do not contest that wildlife and habitat are the target of Secretarial Order 3362, these goals are only indirectly addressed in the EO.

§214 of EO 14008 clearly mandates improved recreational access to public lands through management as follows:

“It is the policy of my Administration to put a new generation of Americans to work conserving our public lands and waters. The Federal Government must protect America’s natural treasures, increase reforestation, improve access to recreation, and increase resilience to wildfires and storms, while creating well-paying union jobs for more Americans, including more opportunities for women and people of color in occupations where they are underrepresented.”

The clear and concise mandate of the EO to improve recreational access to public lands is again repeated in §215 of the EO as follows:

“The initiative shall aim to conserve and restore public lands and waters, bolster community resilience, increase reforestation, increase carbon sequestration in the agricultural sector, protect biodiversity, improve access to recreation, and address the changing climate.”

§217 of EO 14008 also clearly requires improvement of economic contributions from recreation on public lands as follows:

“Plugging leaks in oil and gas wells and reclaiming abandoned mine land can create well-paying union jobs in coal, oil, and gas communities while restoring natural assets, revitalizing recreation economies, and curbing methane emissions.”

The Organizations are aware significant concern raised around the 30 by 30 concept that was also memorialized in EO 14008. While the EO does not define what “protected” means, the EO also provided clear and extensive guidance on other values to be balanced with. From our perspective the fact that large tracts of land in the planning area are Congressionally designated or managed pursuant to Executive Order far exceeds any goals for the EO. While there are overlap between these categories that precludes simply adding these classifications together, this also does not alter the fact the planning area has achieved these goals of 30% of acreages being protected.

The Organizations are aware that the America the Beautiful effort has provided some generalized guidance on implementing EO 14008, and unfortunately these goals are not particularly clear either. While there is a lot of confusion around the goals, the applicability of these goals to federal lands is clearly reflected, in Principle #5 of the America the Beautiful effort, which is as follows:

“Principle 6: Honor Private Property Rights and Support the Voluntary Stewardship Efforts of Private Landowners and Fishers”[27]

Our first question would be why Federal and State ownership would not be sufficient to protect these lands which encompass almost 60% of the State of Colorado. But even from this standard is found insufficient Congressionally protected lands in Colorado are significant. After a cursory review of the federal public lands status in Colorado about 55% of the USFS managed lands are managed as either Congressionally designated Wilderness (15%) or Roadless Areas (35%), which are managed with the specifically identified goals of protecting resources.

For the Department of Interior lands, National Wildlife Refuges encompass around 175,000 acres, National Parks managed areas encompass another 739,000 acres, Congress has designated 2 National Recreation Areas covering more that 78,000 acres and 3 National Conservation Areas covering a little less than 400,000 acres, BLM manages 4 Wilderness Areas covering 248,751 acres and an additional 548,023 acres as Congressionally designated Wilderness Study areas. These lands cover another 14% of the federal lands mass. When these areas are consolidated Colorado has about 35% of the federal land mass under Congressional designations currently. The levels of protections only increase as lands managed by the Bureau of Reclamation and Army Corp of Engineers are not included in this analysis.

Percentages of protection are only further increased by the large number of Colorado State Parks and Wildlife areas that are in the State. Numerous local governments also have extensive holdings that would further increase the percentage of lands that are protected. Given the fact that Colorado has already exceeded the 30×30 goal, we must question how the goal can be furthered as asserted in scoping and related documents. The Organizations are unsure how compliance with EO has been determined as the EO is hugely conflicting and ambiguous on many issues. Without further national guidance on implementation of the 30×30 effort, the Organizations submit that any assertion of further compliance is at best horribly premature.

8. Economic impacts from unintended impacts of management must be addressed.

The Organizations are very concerned around the possible negative economic impacts that could result from the Proposal, not only from recreational related impacts but also the possible impacts to other activities as well. Too many of our small communities’ struggle to provide even basic services to their residents and tourists visiting the areas. Without a well-rounded economic engine for the community, the community will struggle and possibly fail and this will degrade the recreational opportunities and support for them from the community and this is a concern for the Organizations. The Organizations are very concerned that there have been numerous assertions that completely overestimate the economic contribution of the reintroduction by merely asserting that all recreation is occurring in the State as a result of the reintroduction. That entirely lacks factual basis.

CPW own conclusions on the economic contributions of all forms of outdoor recreation in the state of Colorado, clearly identified as a consideration to be mitigated in any NEPA analysis are as follows:

“Focusing on the state-level results below, the total economic output associated with outdoor recreation amounts to $62.5 billion dollars, contributing $35.0 billion dollars to the Gross Domestic Product of the state. This economic activity supports over 511,000 jobs in the state, which represents 18.7% of the entire labor force in Colorado and produces $21.4 billion dollars in salaries and wages. In addition, this output contributes $9.4 billion dollars in local, state and federal tax revenue.” [28]

The Organizations submit that more than $62.5 Billion Dollars of economic contribution that results in 18.7% of the entire labor force is an economic concern to warrant specific recognition of recreation both now and in the future. While many of the planning areas are outside the economic contributions of the Denver Broncos and other recreational activities, the economic contributions of motorized recreation to the state are massive as well and are highly at risk in the current Proposal given the concept of route density being addressed specifically in the Proposal. In 2014, CPW, USFS and BLM partnered with COHVCO to undertake an economic contribution study from the recreational use of off highway motorized vehicles in Colorado.[29] While slightly out of date at this point, these contributions remain immense and were found to account for more than $2.3 billion in economic contributions, more than 17,000 jobs and more than $300 million in tax revenues.

Any assertion that such a massive economic contribution is insufficient to warrant inclusion in NEPA analysis simply lacks any factual basis. It would be highly frustrating to open collaborations when contributions such as this are not worthy of recognition. This type of arbitrary resolution of considerations will cause concern and frustration from the public generally, and our members more specifically, as the Proposal moves forward.

4c. Economic contributions of wildlife tourism are almost non-existent.

Under ESA processes for habitat designations and general NEPA analysis planners are required to address economic impacts of decisions around the reintroduction of the wolves in the ecosystem. We again believe these issues are highly relevant to understanding the climate the Proposal is being developed under. Too often we are hearing comical assertions that wildlife will drive eco-tourism and related economic impacts will simply flow from the reintroduction to local communities.[30] That is simply without factual basis and almost all research we have seen has been hugely generalized and overly broad.

The lack of factual basis of these assertions is exhibited by the fact that wolves were reintroduced into the Yellowstone Park about the same time as snowmobile closures were undertaken in the park. The value of recreation to these local communities is well demonstrated prior to the Yellowstone closures for snowmobiles.[31] While a hugely developed diverse population of wildlife has been on the landscape and easily seen in the winter, tax revenues and jobs from winter recreation in the Yellowstone Park remain only a small fraction of the previous levels. People simply are not visiting these areas to view wildlife in sufficient numbers to offset visitation lost from more generalized recreation. This is highly relevant to this discussion as tourists are not going to Colorado primarily to see wolves, if you are skiing at Steamboat or Vail your decision is driven by a desire to ski not see wildlife.

9. Conclusion

The Organizations participated in the public meetings that were provided by the BLM on this issue and were surprised to hear a FAR more broad scope of the project than is currently provided for. Our experiences with the Sage Grouse management efforts have allowed us to understand that anytime route density standards are addressed, such as in the Proposal, there will be recreational impacts due to route closures. This is a situation where one size fits all management is totally inappropriate and significant amounts of work must be performed on existing data to understand the myriad of site-specific issues that species are facing in the state and what previous management challenges have been faced in these areas. While the state of Colorado may have requested this review, it does not absolve the BLM of basing management decisions on best available science.

The Organizations are very concerned that a significant amount of foundational analysis for the effort does not appear to have occurred and if it has occurred it has not been discussed. The Organizations submit this spans many facets of the Proposal, which ranges from questions like has there been a decline in wildlife populations in Colorado? Is there a single factor causing the perceived decline in wildlife populations? If so, how was this determined. What was the time frame for this conclusion and analysis? How was the relationship between an asserted decline in populations been attributed to a lack of habitat? These are foundational questions that must be addressed before any range of alternatives is even formulated, as our minimal research indicates there are a huge number of factors impacting wildlife populations, ranging from the window of time used to analyze declines or increases, poor data being available for analysis and other management efforts driving down populations based on best available science. Once these other factors are addressed the Organizations vigorously assert the relationship between populations and habitat declines must be established. This simply has not been done to date. If the BLM is going to move forward with any analysis of options as required by NEPA, these are foundational questions that must be addressed.

Please feel free to contact Scott Jones, Esq. at 518-281-5810 or via email at scott.jones46@yahoo.com or Chad Hixon at 719-221-8329 or via email at Chad@Coloradotpa.org if you should wish to discuss these matters further.

Sincerely,

Scott Jones, Esq.

Authorized Representative – COHVCO

Executive Director CSA

Chad Hixon

Executive Director – TPA

Marcus Trusty

President – CORE

[1] See, Executive Order §11644 at §3.

[2] For more information on this program please see the following link: Colorado Parks & Wildlife – OHV Grant Application Forms (state.co.us)

[3] More information on this program is available here: Colorado Parks & Wildlife Partners with Colorado Youth Corps Association – Pagosa Daily Post News Events & Video for Pagosa Springs Colorado

[4] See, CPW Colorado’s Big Game Habitat and Connectivity: Opportunities for Policy Solutions; 2021

[5] A complete copy of this grant is available here: 31-Travel_Management_Signage_2023.pdf (state.co.us)

[6] See, Colorado Parks and Wildlife; Colorado Bighorn Sheep management plan 2009−2019; February 2009 at pg.1.

[7] See, CPW E25 1999 Williams Fork Elk Herd management plan at pg. 4

[8] See, CPW E25 1999 Williams Fork Elk Herd management plan at Pg 11.

[9] See, CPW 2017 E25 Williams Fork Elk Herd management plan at pg. 9.

[10] See, 1999 E25 plan Williams Fork Elk Herd management plan at pg. 25.

[11] See, BLM Gunnison Basin Travel Plan FEIS 2010 at pg. 262. a complete copy of this documentation is available on request.

[12] See, CPW E13 Elk Herd Plan (1999) at pg. 1. As this report is not easily available, we have enclosed a copy as Exhibit “3”

[13] See, WildEarth Guardians webinar at 5 minutes of 1hr 3-minute webinar. A complete copy of this webinar is available for viewing here: Colorado Wolf Restoration Plan webinar – YouTube

[14] See, SAN LUIS VALLEY ECOSYSTEM COUNCIL, SAN JUAN CITIZENS ALLIANCE, THE WILDERNESS SOCIETY, and WILDEARTH GUARDIANS, Petitioners vs. DAN DALLAS; and UNITED STATES FOREST SERVICE; IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO; Civil Action No. 1:21-cv-2994

[15] See, Taylor and Knight; WILDLIFE RESPONSES TO RECREATION AND ASSOCIATED VISITOR PERCEPTIONS; Ecological Applications, 13(4), 2003, pp. 951–963

[16] See, Western Governor Assoc; Case Study: State, Federal, Local and Private Entities Collaborate to Build Wildlife Crossings along a 12-Mile Stretch of Highway 89 in Southern Utah 2014 at pg. 4. A complete copy of this study has been attached as Exhibit “4”to these comments.

[17] See, DOI Secretarial Order 3362 @ §4(b)(2)

[18] See, Millspaugh et al: Models for planning wildlife conservation in Large Landscapes; Elsiver Press 2009 at pg. 51.

[19] See, Millspaugh et al; Note #10 at pg. 51.

[20] See, Carroll et al; Biological and Sociopolitical Sources of Uncertainty in Population Viability Analysis for Endangered Species Recovery Planning; Scientific Reports; July 12, 2019

[21] See, Wikipedia.com; definition of scientific modeling @ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scientific_modelling accessed September 1, 2020

[22] See, Zwilling, Martin: 7 Steps for Establishing the Right Business Model; January 30, 2015.

[23] See, https://www.wikihow.com/Make-a-Mathematical-Model

[24] See, Orloff & Strong; Models for planning wildlife conservation in large landscapes; 2009

[25] See, Millspaugh et al; Models for Planning Wildlife Conservation in Large Landscapes, Elsiver Publishing 2009 at pg. 5. Internal citations omitted

[26] See, US Fish and Wildlife Service; Proposed Rules; Endangered and Threatened Plants and Wildlife; Designation of critical habitat for the Mississippi Gopher Frog; Federal Register; Vol. 75, No. 106 pg. 31387; Thursday, June 3, 2010 at pg. 31404.

[27] See, US Government Interagency Report: Conserving and Restoring America the Beautiful; 2021 at pg 15. A complete copy of this report is available here. Report: Conserving and Restoring America the Beautiful 2021 (doi.gov)

[28] See, CPW 2017 Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan: Appendix F Pg. 111. Dated July 23, 2018.

[29] A complete copy of this study has been provided with these comments as Exhibit “6”

[30] The Economic Benefits and Struggles of Wolves in Yellowstone | Good Nature Travel Blog (nathab.com)

[31] See, Taylor et al; Economic Importance of the Winter Season to Park County, Wyoming, May 1999.

Thank you Monarch Investment and Management Group for your support of a strategic planning process that the TPA has underway.

Thank you Monarch Investment and Management Group for your support of a strategic planning process that the TPA has underway.