BLM Moab Field Office

Attn: Labyrinth/Gemini Bridges Travel Management

82 East Dogwood

Moab, UT 84532

Re: Labyrinth Rims/Gemini Bridges Travel Management Plan

EA #DOI-BLM-UT-Y010-2020-0097-EA

Dear Planning Team Members:

The Trails Preservation Alliance and Ride with Respect appreciate the opportunity to submit the following comments on the above-referenced draft Environmental Assessment:

1. The BLM should start the present NEPA process over and issue a Notice of Intent to do a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) instead of an Environmental Assessment (EA)/Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), because alternatives are being seriously considered, which if adopted would significantly impact the human, socio-economic environment, for NEPA purposes.

This EA/FONSI process cannot stand the test of validity, because such a high percentage of established open roads and trails are being considered for permanent closure in the planning area—a globally recognized motorized recreation destination of unquestioned significant economic and cultural value in the planning area, in adjacent communities, and really in the entire State of Utah and much of Colorado. The Trails Preservation Alliance and Ride with Respect advocate to keep such roads and trails open (Alternative A), or at worst adopt an alternative that only scarcely reduces access to such roads and trails, in either of which cases the “impact” to the human, socio-economic environment would not be “significant” for FONSI purposes.

However, the mere fact that alternatives are just being seriously considered, that would greatly reduce the motorized recreation values in the planning area, demonstrates the legal necessity of converting this process to a full-blown EIS process. Again, a finding of no significant impact would not stand the test of validity under some of the alternatives being seriously considered, as such closures portend impacts to the human, socio-economic environment that are significant, and the human, socio-economic environment is just as much the “environment” for NEPA purposes, as any other resource value at issue here.

Without waiving the foregoing request to re-launch this process as an EIS, the Organizations, under respectful protest, participate in this comment period during the current EA process, by submitting the additional points that follow.

2. Introduction

Please accept this correspondence as the input on the Labyrinth Rims/Gemini Bridges Travel Management Plan (“The Proposal”) of the Organizations identified above. The Proposal fails to properly apply relevant federal law and settlement agreements that the motorized community has been party to, and the Proposal fails to recognize that it may have significant negative pre-decisional impacts on other efforts that are ongoing in the Field Office and planning area. Each of these challenges are presented in addition to noting the direct conflict between the Proposal and basic NEPA requirements and practices.

Too often the Proposal fails to correctly apply Congressional actions and determinations on the management of Congressionally designated areas, such as Wild and Scenic River areas and management of the Old Spanish Trail. Often the Proposal seeks to exclude usages that are identified by Congress as defining characteristics of these areas. Moreover, the Proposal seeks to elevate usages that are low in priority for the Congressionally designated areas. Given the systemic failures throughout the Proposal, the Organizations have no choice but to support Alternative A and request that the Proposal be reviewed for basic consistency with the applicable federal laws. Once corrected, the Proposal should be released to the public for a meaningful comment period. Alternative D once appeared at first blush to be something the Organizations could support, we are unable to do so on closer review as the Proposal’s overall range of alternatives is artificially skewed due to defects in the planning process.

3. Who We Are

Prior to addressing the specific concerns of the Organizations regarding the Proposal, here is a brief summary about the Organizations submitting these comments.

The Organizations, their counsel, or affiliates including groups for which the Organizations are members, have been involved in discussions with the BLM for decades, both concerning access to these areas in general and concerning the development of travel and resources management plans for these areas. In addition to the planning efforts, our involvement has continued on behalf of recreation interests in litigation by the Organizations, their counsel, or affiliates including groups for which the Organizations are members. This work stretches from the Settlement in SUWA v. U.S. DOI, Case No. 2:12-cv-257 DAK (D. Utah) to bringing successful jurisdictional challenges in SUWA v. Babbitt, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22170 (D. Utah 2000), rev’d, 301 F.3d 1217 (10th Cir. 2002), rev’d and remanded, Norton v. SUWA, 542 U.S. 55 (2004). We remain committed to this presence in ongoing management of Utah BLM lands. Many of our local partners have intervened in defense of the BLM when its plans and decisions were legally challenged. Some of these efforts have resulted from the 2017 SA now being implemented, and we continue to be involved with planning/travel efforts throughout the region. We have worked diligently to support these efforts in many ways. While we understand the difficulties that the BLM has encountered in the management of this area, we believe strongly that all recreational interests must be allowed access to the planning area, as it is one of an increasingly few parts of the region left in true multiple-use management.

Moving forward with the successful path that has been developed for this area is the right way forward in the Organizations’ opinion, but the Proposal does not provide for or follow that path. Arbitrary decisions have been made on which to base the Proposal, and the Proposal appears to rely on Supreme Court decisions that are not germane to the management of NTSA routes. Moreover, pre-decisional actions impacting camping resource planning call the validity of the Proposal into question. Routes and opportunities at issue in the Proposal are world class; they are worthy of expert and thorough analysis that the Proposal currently does not provide.

The Trails Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is an advocacy organization created to be a viable partner to public lands managers, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of motorized trail riding and multiple-use recreation. The TPA acts as an advocate for the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate a fair and equitable percentage of public lands access to diverse multiple-use trail recreational opportunities.

Ride with Respect (“RwR”) was founded in 2002 to conserve shared-use trails and their surroundings. RwR has educated visitors and performed over twenty-thousand hours of high-quality trail work on public lands including several-thousand hours in the planning area such as rerouting over a dozen trails away from sensitive resources through travel-plan amendments of the 2008 RMP. Over 750 individuals have contributed money or volunteered time to the organization.

Collectively, the TPA and RwR are referred to as “The Organizations” herein.

4. The 45-day comment period provided is arbitrarily brief and does not reflect the recreational value of the routes in the area. It should be extended at least another 45 days.

The Organizations strongly object to the unreasonably short comment period that has been provided for the Proposal. While 45 days may be slightly more than the minimum required by law, 45 days is far too short for the public to digest and provide meaningful input on the Proposal. The goal of this effort should be to provide a high quality meaningful plan for the management of the area that is based on high quality data and analysis. That goal is not evident in the Proposal as it does not adequately reflect the global values of the subject routes being addressed.

The short response time frame was made even shorter by how the basic data for the Proposal was rolled out well. Original versions of maps and other information were often incomplete, contradictory and an obstacle to public engagement, instead of the detailed high quality information that NEPA requires. Often routes were identified as closed in PDF versions of alternative maps but were identified as open in GIS data for the same alternative provided with the Proposal. Other routes were only partially reflected in maps provided, as start or finish locations might have been identified but are simply not connected. This is conflicted further by the fact that managers often informed the public that routes were open or closed in alternatives when the data and mapping indicated otherwise. The BLM should have completely released all pertinent information prior to commencing this NEPA process.

The BLM has the authority to extend the public comment deadline as we are requesting. Refusing this request on the guise of avoiding further delay makes no sense. Because the development phase of this EA took years, the all-important public process should not be compromised just because the BLM took so long in development. Long development phases mean longer time for public review and comment. That is only fair.

5. Alternatives B and C fundamentally violate the Moab FO RMP and hence NEPA, FLPMA and the APA.

5(a).The planning area’s existing route network underwent extensive analysis in 2008, and that analysis, documented heavily in the 2008 RMP, strongly supports the existing route network for all issues except the additional review agreed to in the 2017 Settlement Agreement (2017 SA).

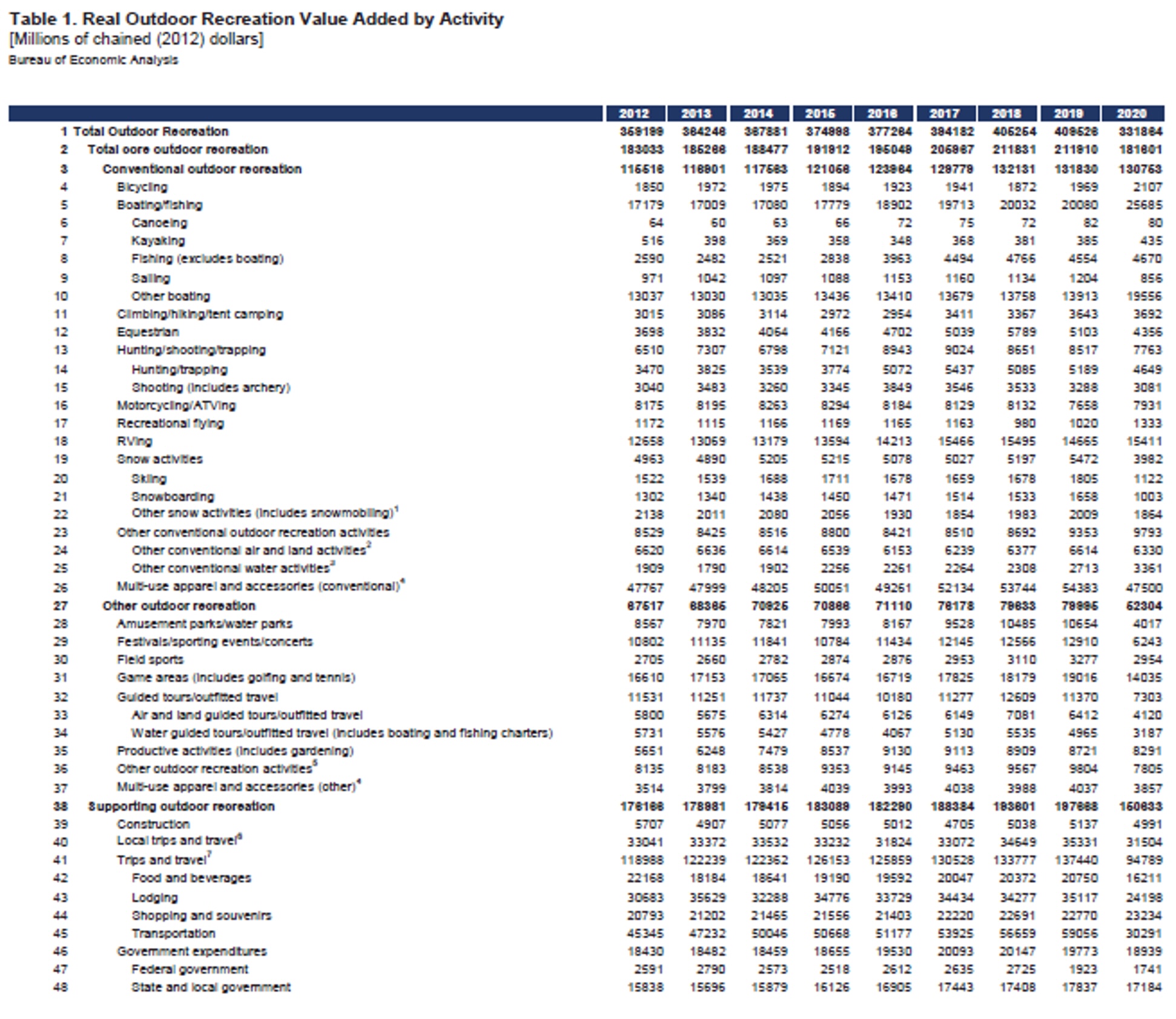

The 2017 SA left the BLM free to add routes to the current TMP (whether the routes are existing or even just proposed for construction), as much as subtract routes from the current TMP, as much as make no changes at all to the current TMP. In short, the 2017 SA did not obligate, let alone authorize, any sort of bias or pre-decision on the BLM’s part when revisiting TMPs. Further, the BLM had already obviously demonstrated minimization when the 2008 TMP closed 40% of the routes that were inventoried by 2003 in this planning area, many of which were in lands with inventoried wilderness characteristics.

At the very least, the 2017 SA did not relieve the BLM of its FLPMA and NEPA obligations to conduct a full-scale EIS and amendment of the 2008 RMP before considering changes to polygon-based, wilderness characteristics management suitability determinations. But that is what alternatives B and C effectively do, by presuming that all routes in lands with wilderness characteristics polygons should be closed by default unless proven again to have an overriding purpose and need. The 2017 SA did not authorize such an unfounded reversal of presumptions, especially given that the routes up for closure in alternatives B and C were verified to exist and thoroughly analyzed in the 2008 RMP, and given, as stated above, the BLM had already undergone a rigorous minimization in 2008 and still had just as free of a hand under the SA to add routes to the current TMP as it did to subtract routes. This reversal of presumptions and resulting massive-scale proposed closure in polygons determined not suitable for WC management, evidences the BLM’s shirking of its FLPMA and NEPA obligations.

The mistaken nature of the BLM’s reversed presumption is further shown by the fact that virtually all existing routes, particularly the 60% of existing routes that were left open by the 2008 TMP, provide some recreational value even if they’re low in use (and even if they have some degree of revegetation). Granted, if a new route is proposed for construction, the onus may be on justifying its purpose. The Proposal considers only existing routes, in fact only those routes currently designated open, so the onus should be justifying what the purpose would be of closing them.

The following cannot be emphasized enough: How thorough was that 2008 analysis and minimization of existing routes? Thorough enough that approximately 40% of inventoried motorized routes in the current planning area were closed. That is the fruit of the 2008 RMP. Further underscoring the presumptive validity of the 2008 RMP, the Moab Field Office’s 2015 review of the effectiveness of the 2008 RMP, found that the current recreation management strategies are working well and there was no need to amend the 2008 RMP. The upshot is that the remaining routes which survived that rigorous 2008 analysis and wholesale cuts, bear the controlling imprimatur of valid purpose and need, subject only to the required additional review scoped in the 2017 SA.

It is unfounded to draw from this background and context the mistaken presumption that all routes in the current planning area are worthy of closure unless they are once again re-proven to validly serve a purpose and need. This reversal of presumptions and resulting looming closure of still another 40% of routes, is a material legal flaw of the Proposal’s action alternatives to varying degrees. Thus the obvious wholesale suitability changes contemplated in alternatives B and C can be legitimately adopted only through an RMP amendment.[1]

5(b).Alternatives B and C run headlong into the 2008 RMP’s rejection of the invitation to conform motorized travel management to the pro Red Rock Wilderness Proposal alternative.

During development of the 2008 RMP, wilderness-expansion groups tried to court the Moab FO into manufacturing wilderness by eliminating the roads that were anathema to the groups’ Red Rock Wilderness Proposal. The 2008 RMP ROD at Page 13 rejected this invitation:

The RRH [Redrock Heritage Travel Plan Alternative] plan’s roadless polygons match almost identically with wilderness proposals submitted by Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA) and/or other interest groups. To achieve this “roadlessness,” RRH has recommended for closure virtually all roads within these proposed wilderness polygons, without specific mention or regard for purpose and need.

…

The RRH Travel Plan mirrors the Red Rock Wilderness proposal, which encompasses over 46 percent of public lands in the MPA. RRH assumes that if currently available motorized routes were eliminated, these areas would be eligible for the protection of their wilderness characteristics.

…

Almost all of these routes and areas lie within RRH wilderness proposals. In its comments, there is repeated emphasis on the need to set aside areas for non-motorized recreation and, if necessary, to “create a rare remote and wild area.” Current BLM policy prohibits the creation of new wilderness study areas, although it does allow managing areas to protect wilderness characteristics. Several of the areas cited in RRH’s proposal were found by BLM in 1999 to lack wilderness character. Many of the specific routes identified by RRH were either described as roads in the BLM 1999 inventory or described as roads at the time of the establishment of the original WSAs. Roads, by definition, are an impact on wilderness characteristics.

Alternatives B and C of the current draft EA are attempts at an “end around” of the controlling 2008 RMP’s stance against creating de facto wilderness through road closures.

5(c). Alternatives B and C run headlong into the 2008 RMP’s rejection of the invitation to manage for alleged wilderness characteristics in areas found not suitable for wilderness characteristics management.

The near complete overlap between the concentrations of road closure under alternatives B and C of the Proposal, and the polygons for wilderness designation/wilderness characteristics management perennially demanded by wilderness-expansion groups, is too great to be legitimately coincidental. It belies a conscious, illegitimate purpose, a purpose to undermine the non-suitability management determinations of the 2008 RMP. While several areas within the Labyrinth Rims/Gemini Bridges TMA are considered Lands With Wilderness Characteristics, the 2008 RMP expressly decided those areas were not suitable for wilderness characteristics management due to their high density of popular motorized routes. In short, alternatives B and C attempt an “end around” the 2008 RMP’s controlling stance against managing for wilderness characteristics, lands for which the 2008 RMP determined are not suitable.

Further, as stated above, even though the 2008 RMP determined none of the current planning area to be suitable for wilderness characteristics management, it did minimize impacts to lands with wilderness characteristics within the current planning area by closing many existing routes for other purposes. The Proposal should recognize the minimization already done in all of the current alternatives including Alternative A.

6. Alternatives B and C effectively ignore the Congressional prohibition on wilderness buffer zones adjacent to Labyrinth Canyon in Emery County.

The 2019 Dingell Act passed by Congress created the Labyrinth Canyon Wilderness Area on the other side of the Green River from the Labyrinth Rims/Gemini Bridges TMA. But Congress expressly mandated against wilderness-type management in so-called buffer zones adjacent to any wilderness areas created in the Dingell Act. Moreover Congress left the Labyrinth Rims/Gemini Bridges TMA for continued multiple-use management that includes motorized recreation. The BLM should reject alternatives B and C for the additional reason that they essentially create a de facto wilderness zone to “buffer” the Labyrinth Canyon Wilderness. Sight and sound impacts experienced in Labyrinth Canyon are simply irrelevant and immaterial to the question of how to manage the Labyrinth Rims/Gemini Bridges TMA.

Moreover the Green River’s Wild and Scenic River designation does not justify buffer zone management either, as the Scenic designation for the relevant river segment does not limit motorized use within the corridor, let alone limit use outside of the corridor. Compliance with the Dingell Act’s mandate against buffer management for the Labyrinth Canyon Wilderness and management of Labyrinth Canyon as a Scenic River (and not a Wild River) is only possible by rejecting alternatives B and C of the Proposal.

7(a). The mapping issues displayed in the Draft EA Proposal should be corrected.

Problems with the Proposal’s maps were immediately identified by the OHV community after the Proposal’s initial release. Yet agency managers waited a significant time to post PDF maps of the revised alternatives from scoping. The BLM’s e-Planning page has a maps tab, which is still showing the PDF maps for the preliminary alternatives for all except Alternative B. The main documents tab includes PDF maps for all the updated alternatives; however, these maps do not match either the BLM’s GIS data files or the alternative actions listed in the individual route report files. More significantly, many discussions with BLM staff on concerns around a particular route have been based on information that is not reflected in any of the maps. As a result, the public have been forced to devote significant time in the 45-day comment period just trying to understand what each alternative actually proposes. That is not acceptable. Basic notions of Moab FO pride and professionalism dictate that you correct these mapping issues and give the public significantly more time for review and comment with proper mapping in hand.

On top of delays and inaccuracies, the PDF maps provided are not sufficient for the general public to follow. They are 11″ x 17″ pages representing a planning area that’s over 300,000 acres, containing no place names, and no way to tell which routes are the graded (Class B) roads that visitors use to orient themselves to the area. In addition to improving these maps, the BLM should have included alternatives B, C, and D as layers in the interactive map that it posted on ePlanning. The Moab FO demonstrated this capability when posting all of the alternatives as layers in the interactive map for the Canyon Rims travel plan, a planning area that didn’t have nearly the public interest of Labyrinth Rims/Gemini Bridges. Further, when clicking on a route, the interactive map should display more GIS fields than simply the route number and length such as the dates of a seasonal closure. In fact, clicking a route on the interactive map ought to provide most or all contents of the route report, as currently the public can only view a route report by downloading a 650MB-folder of all route reports. The fact that the interactive map shows only Alternative A and lists only the route number and length prevents most members of the public from understanding which actual routes on the ground are open/closed or limited by width/season in each alternative.

When PDF maps were finally released, there were immediate and significant conflicts with other documents that had been provided. This challenged understanding of even Alternative A as the Proposal did not align with routes on the ground nor accurately reflected the open status of some globally recognized routes. According to the GIS files that BLM provided, examples of serious errors with PDF maps throughout each alternative are:

- The upper part of the Mineral Canyon trail shows as open with a seasonal closure when it is actually closed and limited to administrative use;

- The Bull Canyon Overlook trail shows as closed when it is actually open with a seasonal closure;

- Newly added closures are not shown in several alternatives for several key segments of the Seven Mile Rim Jeep Safari trail;

- Alternative B was modified to close parts of the Seven Mile Rim trail as requested by Grand County. However, it appears those same closures were incorporated into Alternative C as well, but that is not reflected in the PDF maps;

- The current version of Alternative C will now close the most iconic section of the Seven Mile Rim trail across the slickrock bench below Monitor and Merrimac Buttes to the top of Wipeout Hill;

- It will also close the segment through Tusher Wash leading over to the Tusher Tunnel area. This is the only connector route between the Courthouse Rock trail system and the Tusher Canyon trail system, so those are now isolated from each other; and

- A third segment of the Seven Mile Rim trail by the overlook of highway 313 is also closed. This closure, plus the closure in Tusher Wash, would leave several route segments designated open orphaned with no legal routes accessing them.

The impact of these mapping errors on alternatives is significant and prejudicial to the public’s ability to comment on particular areas or concerns. The preliminary version of Alternative C is problematic. , But the updated version is significantly more so, because it negatively affects one of the most iconic Jeep safari trails and takes away trail connectivity in the Courthouse Rock area. To whatever extent the commenting public may have supported this alternative early after the Proposal’s release, the final version of Alternative C is significantly different and it is unknown if those members of the public are even aware of the changes in the alternative based on the “corrections”.

7(b). NEPA violations have been created by the haphazard release of inaccurate maps for the Proposal.

The Organizations addressed above the seriously problematic nature of the mapping information that has been provided by the EA. This violates NEPA as the public has not been provided detailed high-quality information about the Proposal on which to comment. Rather information that’s critical to commenting on the Proposal has been slow to be provided and often contradictory in nature. Courts have specifically addressed the haphazard release of information in this manner as follows:

Of course, all of these Section 102 duties are qualified by the phrase “to the fullest extent possible.” We must stress as forcefully as possible that this language does not provide an escape hatch for footdragging agencies; it does not make NEPA’s procedural requirements somehow “discretionary.” Congress did not intend the Act to be such a paper tiger. Indeed, the requirement of environmental consideration “to the fullest extent possible” sets a high standard for the agencies, a standard which must be rigorously enforced by the reviewing courts.[2]

All of this lends to optics suggestive of agency foot-dragging, which by itself has been found to violate NEPA. For this reason alone, the Proposal should be returned to the agency for a full review of data and maps for basic consistency, and then released for an adequate period of time for the public to comment. Right now, it is not an overstatement to say that the public cannot understand what is actually being proposed.

7(c). 2017 Settlement Agreement provisions regarding preliminary route proposals have been violated.

As the Organizations have specifically noted previously, we have participated in the development of these plans since day one and our interests had intervened in defense of the BLM when challenges were made to previous decisions. As a result of our status as a party to the litigation, we are also aware that the January 2017 SA specified that written comment would be taken from partners. The 2017 SA further specified that, prior to the release of the Draft EA, the BLM may seek further public and stakeholder input on the maps of preliminary alternatives and other documents “commensurate with the level of public and stakeholder interest,” which is obviously quite high for this travel plan. Not only did this public process not occur, all information to date in the effort remains of exceptionally low quality and often totally unavailable to the public to review for a wide range of issues even during the EA release. The Organizations are intimately aware that this pre-NEPA public process was designed to create consistent and accurate information for the NEPA process. The Organizations are concerned about the general status of this effort, after the original Proposal was overturned by the Court’s acceptance of the 2017 SA that was based on poor route information being available and analyzed in the earlier effort.

The 2017 SA explicitly outlines this requirement for additional public input prior to the commencement of NEPA as follows:

“d. Public and stakeholder review of preliminary route evaluations. At the conclusion of the ID Team’s preliminary evaluation of all the routes being considered for designation in the TMP, BLM will prepare (1) a Travel Management Plan Scoping Report, including an appendix with copies of all public and stakeholder correspondence received to date, unless prohibited by law; (2) preliminary alternatives maps; and (3) draft route reports. BLM will make these documents available to the public and stakeholders upon completion. Commensurate with the level of public and stakeholder interest, BLM may seek further public and stakeholder input as to the preliminary alternatives maps and draft route reports and/or hold a public meeting to further engage the public in the travel planning process. All written input received from the public and stakeholders will be made available to the public as provided by law.”[3]

The Organizations are not aware of any public outreach that occurred before scoping of the Proposal, as required by NEPA, was commenced in April of 2021 despite the fact that above provisions clearly require additional outreach beyond mere compliance with NEPA requirements. There is no mention of this type of outreach in the Proposal either. Even if this outreach had occurred, the Organizations would have to question the value of the effort given the haphazard nature of data that is available currently.

This type of pre-NEPA public review is becoming commonplace with land managers as exemplified by pre-NEPA public release of Forest Plan revisions by the GMUG NF in Colorado and also the Ashley NF and Manti-LaSal NF in Utah. Clearly the above provisions require additional public input on the finalized draft of the Proposal. Compliance with the 2017 SA requirements of pre-NEPA public engagement would have resulted in a more meaningful public process once that NEPA was commenced, as the currently basic problems persist around the accuracy of mapping data.

The 2017 SA’s requirement for additional public input on revised maps has not been honored. During the scoping process, many users identified inaccuracies in mapping information. Impediments to the public process are what the 2017 SA provisions were designed to address and prevent prior to the NEPA process moving forward. Rather than fixing these errors and rescoping the effort, agency managers have chosen to move forward without the benefit of scoping under NEPA requirements based on accurate information.

While technical difficulties such as this might be acceptable with a longer comment period, such as a 90 day comment period, the impact of data being delayed a week is an almost insurmountable barrier to the public review process under a 45-day comment period. These types of problems negate assertions of compliance with the 2017 SA, as the public still is unable to understand what the final revised maps for the area are actually proposing.

8(a). Foundational decisions around the scope of the Proposal are factually unsupported and they conflict with the RMP and supplemental documents.

In addition to the unreasonably short comment period that has been provided, arbitrary decisions limiting the scope of analysis have been made prior to analysis in the Proposal even starting. These are foundational decisions critical to the scope and direction of the Proposal. As an example, the Proposal summarily dismisses the possibility of any new routes in the planning are as they are outside the scope of analysis as follows:

Construction of new routes is not in the scope of this project; however, the possibility of future addition of new routes is part of the operation and management of the overall travel network (see Appendix L (TMP Implementation Guide), Section L.3.5). [4]

No basis or analysis is provided to address how and why this decision was found to be a viable starting point for the EA. This is concerning as all information we are able to locate identifies that this is not a viable starting point for analysis, given the huge increase in visitation to the area since the previous round of closures impacted more than 40% of the routes on the Moab FO. The unreasonableness of this starting position is further supported by the fact that the EA clearly states there are no resource impacts from multiple use recreation on the trail network.

Rather than clearly analyze why the “no new trails” position was found to be a suitable starting point of analysis; the Proposal appears to hint that these decisions are the result of provisions in the 2017 SA. That is unfounded as the 2017 SA allows new routes to be addressed under the settlement and subsequent NEPA, which is addressed as follows:

Nothing in this Settlement Agreement shall be construed to require BLM to adopt any particular alternative or portion thereof presented in a route report or NEPA document or to limit in any way BLM’s discretion to make route designations or adopt a final TMP, consistent with paragraph 2. Nothing in this Settlement Agreement shall be construed to limit in any way BLM’s discretion to open, close, or modify use on routes.[5]

Not only is the “no new trails” provision not supported by the 2017 SA, it also conflicts with the RMP provisions addressing the future of the SRMA. The RMP clearly and specifically identifies goals and objectives for the future development of the SRMA. The RMP starts with a generalized vision for the management of the area as follows:

- “Manage backcountry areas to facilitate scenic motorized touring on designated routes with special emphasis upon establishment of low-development, end of route parking areas and route signing.

- Improve the road to the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trailhead to accommodate passenger car traffic.”[6]

Had there been a desire to limit or restrict access to the area, such as with application of a cap on new trail, that would have been found in these provisions providing a general vision for the area moving forward. Rather than providing this type of limitation, the general vision for the area identified that the goal was to provide quality recreational experiences for all types of users.

The RMP further expands on the vision of quality recreational activity by identifying numerous specific improvements that are to be provided in the planning areas as follows:

“Future Facilities:

- Bartlett Campground: camping in this area will be restricted to this campground.

- Lone Mesa Campground: camping in this area will be restricted to this campground.

- Blue Hills Road OHV Trailhead.

- Courthouse Rock Campground, camping in this area will be restricted to the campground.

- Cowboy Camp Campground, camping in this area will be restricted to this campground.

- White Wash Sand Dunes OHV Parking and Camping Area.

- Gemini Bridges Parking Area and Trailhead.”[7]

None of these site-specific proposals are even mentioned in the range of alternatives of the Proposal. The RMP clearly provides that expansion of routes in the SRMA is specifically a general goal of the designation as follows:

Focus Area — Motorized Backcountry Touring:

Gemini Bridges/Poison Spider Mesa Focus Area (16,299 acres) for multiple use, including full-size OHV, ATV, and motorcycle use with consideration given to managing routes suitable for each vehicle type. Travel will be intensively managed on designated routes only. Close the spur route to Gemini Bridges to facilitate public use and help restore damaged lands along the spur route. Construct a parking area near the bridges.[8]

Not only are there foundational problems with the general vision for the area and specific expansion commitments that were made during the RMP development, the various alternatives specifically conflict with commitments to keep specific routes open that were made during the development of the RMP. Closing key parts of the Seven Mile Rim trail also directly violates the Moab Field Office Resource Management Plan, which expressly mandates that it remain open as follows:

Mill Canyon/Upper Courthouse Mountain Biking Focus Area (5,744 acres) inclusive of areas within the Mill Canyon and upper Courthouse drainages with continued use of the Seven Mile Rim Jeep Safari route for motorized use, with non-motorized trailheads near the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trail and the Halfway Stage Station. Manage the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trail for hiking only (35 miles of road designated for motorized travel; 23 miles of route managed for mechanized use only).[9]

Despite the clarity regarding the Seven Mile Rim road’s future in areas that might have other management priorities, several of the alternatives proposed to close all or some of this route. The impact that this type of decision making will have on public support in anything the Field Office (“FO”)does now or into the foreseeable future is significant and cannot be overlooked.

Not only is the “no new trails” starting point in direct conflict with the RMP for the area, it is in direct conflict with subsequent monitoring efforts for the area performed by the BLM. In 2015 BLM prepared an evaluation of the current status of the RMP for the Moab FO. This analysis of the existing RMP provisions admitted that visitation to the Moab FO was significantly increasing creating a compelling need for new trails as follows:

2.8. Recreation and Travel Management

Visitation has increased dramatically – especially motorized use – in the Moab Field Office since the RMP was completed in 2008. To address the increased pressure on existing areas, travel management and resource protection measures are being implemented at an enhanced rate, when staffing allows. Construction of recreation facilities such as campgrounds, trailheads and trails are a priority.”[10]

Trail building was identified as a priority for the area in the 2015 assessment of the management situation. The assessment recommended speeding expansion of all forms of recreational access to the Moab FO. This recommendation with the Proposal position that the starting point of analysis is “no new trails,” and this significant change in direction and vision for the area is simply never addressed.

The draft Propoal’s vision for analyzing this area differs sharply from the RMP’s controlling vision that recognized recreational usage as a purpose and need for every route. By ignoring the mandatory 2015 FO Evaluation, the draft Proposal essentially undermines it. Furthermore, there is no explanation of how any of the Alternatives will comply with the RMP’s goals and objectives of managing the area for all types of usages. The RMP and 2017 SA specifically allow new routes to be created. A decision not to allow such will come off as unfounded and frankly arbitrary, especially since the RMP mandated periodic evaluation of the area clearly identifies trail building as a priority for the entire field office.

8(b). Visitation and recreational resource capacity assumptions provided in the Proposal are illogical and not factually supported.

There can be no argument that the visitation to Moab FO has skyrocketed in the past decade and much of this has resulted from strong tourism efforts from the local community. BLM has recognized this significant spike in recreational visitation in other planning efforts, such as the recent slack lining EA issued by the Moab FO in 2020. The huge increase in visitation is outlined in the slack lining EA by the BLM as follows:

In the past decade, tourism in the Moab Field Office has increased over 58%; in 2019, the Field Office hosted 1.9 million visitors, and over 3 million visitor days. During the same period, visitation increased by over 72% in nearby Canyonlands National Park.[11]

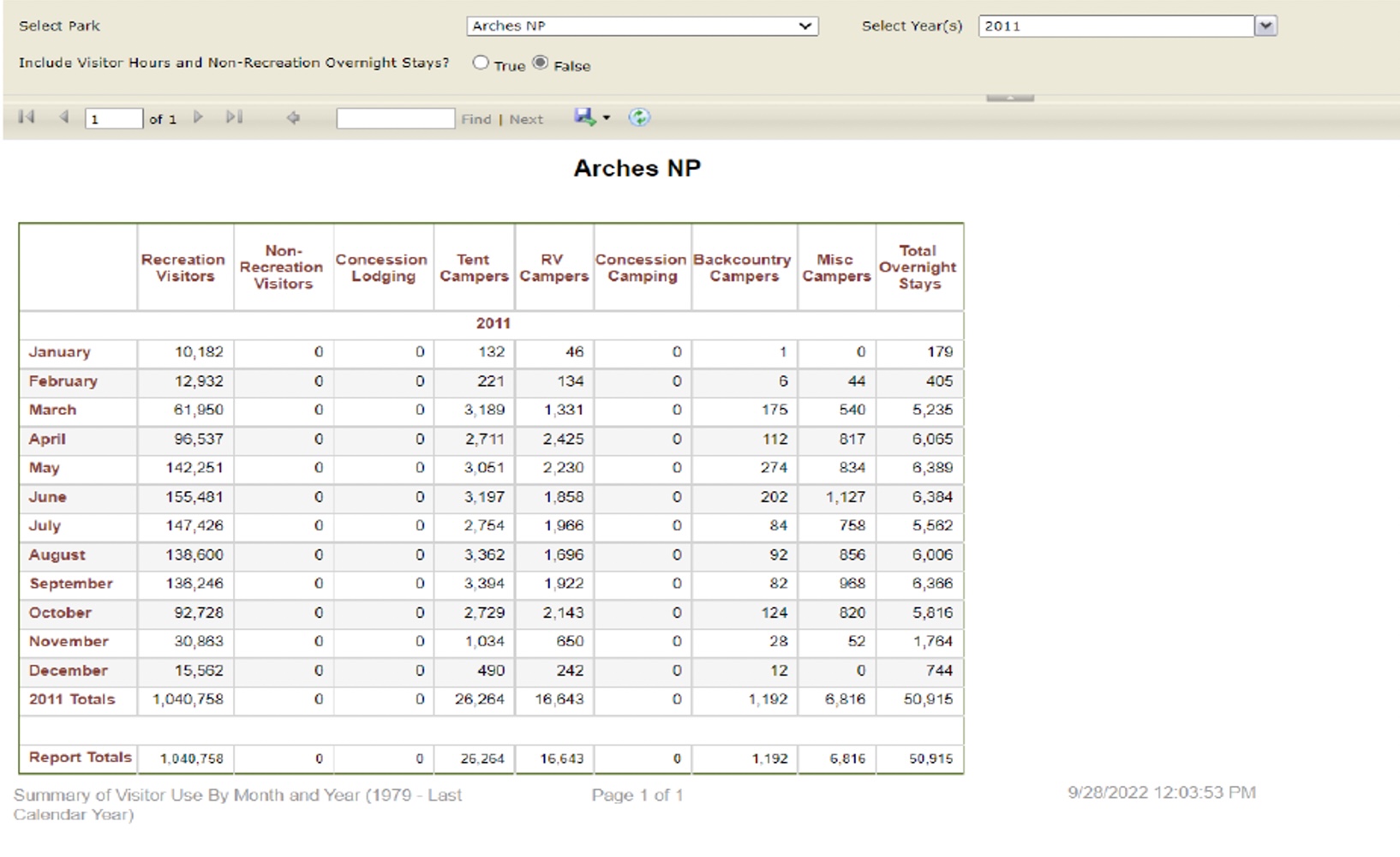

The large increase in visitation to the area has been noted by other DOI managers in planning efforts as well. The National Park Service offices for Arches National Parks have also identified this catastrophic increase in visitation as follows: [12]

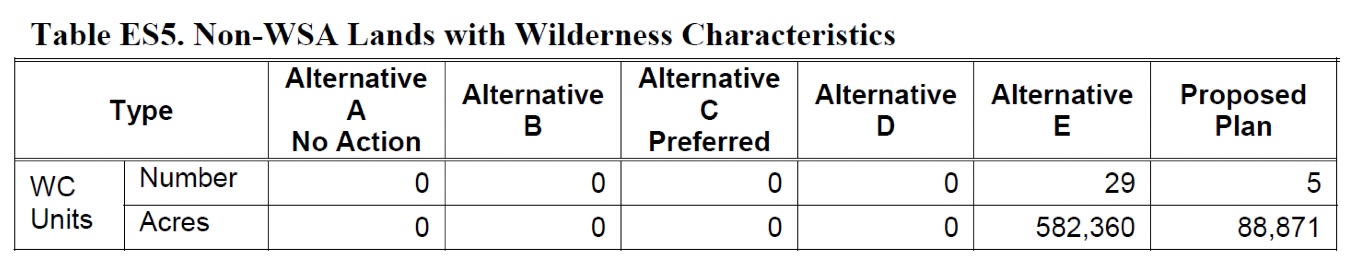

By comparison the Park Service estimated that visitation to Arches NP in 2011 as follows:[13]

These Park Service data efforts conclude that visitation to the Arches National Park has doubled in the last 10 years, and this would be consistent with planning documents throughout the area. We have no reason to anticipate that visitation to the planning area has not increased at a similarly high level. Rather than recognize the unexpected increase in visitation to the area, the Proposal never mentions this challenge or how it may impact the Proposal moving forward. This situation creates another foundational problem for the Proposal and the decision to prohibit new routes in the planning area, as we are unable to understand how quality trail experiences can be provided by a trail network that has been reduced by 40% of total mileage and usage has doubled. This position is outlined in the Proposal as follows:

-

- Reducing network mileage within the TMA is not anticipated to result in a reduction in OHV use overall. Year-round OHV and non-motorized recreation use is expected to continue to increase slightly in and around the TMA regardless of the designations made as a result of this travel planning effort.

-

- Concentration of use as a result of OHV-Closed designations is not anticipated as an issue in this TMA. This conclusion was reached by the BLM IDT and applies for archaeology, wildlife, and other resources. Many of the routes proposed for OHV-Closed designations in the alternative networks are very lightly used, and therefore would not result in any appreciable concentration of use on the remaining open routes.[14]

Characterizing as “slightly increasing” a demonstrated two-fold increase in visitation to the area is unfounded. It fails as the kind of proper analysis of this issue that NEPA requires in the Proposal. NEPA requires high-quality information to support the decision-making process.. Commenting regarding this type of assumption and dearth of supporting data is impossible. It renders a decision-making process that NEPA sought to avoid.

8(c). Quality recreational access that is mandated in the RMP objectives will be denied by closures of 40%.

The Proposal should recognize and address the fact that significant restrictions to the planning area have resulted from recent planning efforts. These are highly relevant to the continued decline in the quality of motorized opportunities in the planning area. They directly undermine any assertion that there is excess capacity in the motorized route system sufficient to absorb significant increases in area visitation. There has been a significant increase in dissatisfaction of motorized users since the 2008 restrictions, and this has also forced many motorized users to other areas, such as Grand Junction FO and GMUG in Colorado, in order to obtain quality dispersed recreational experiences.

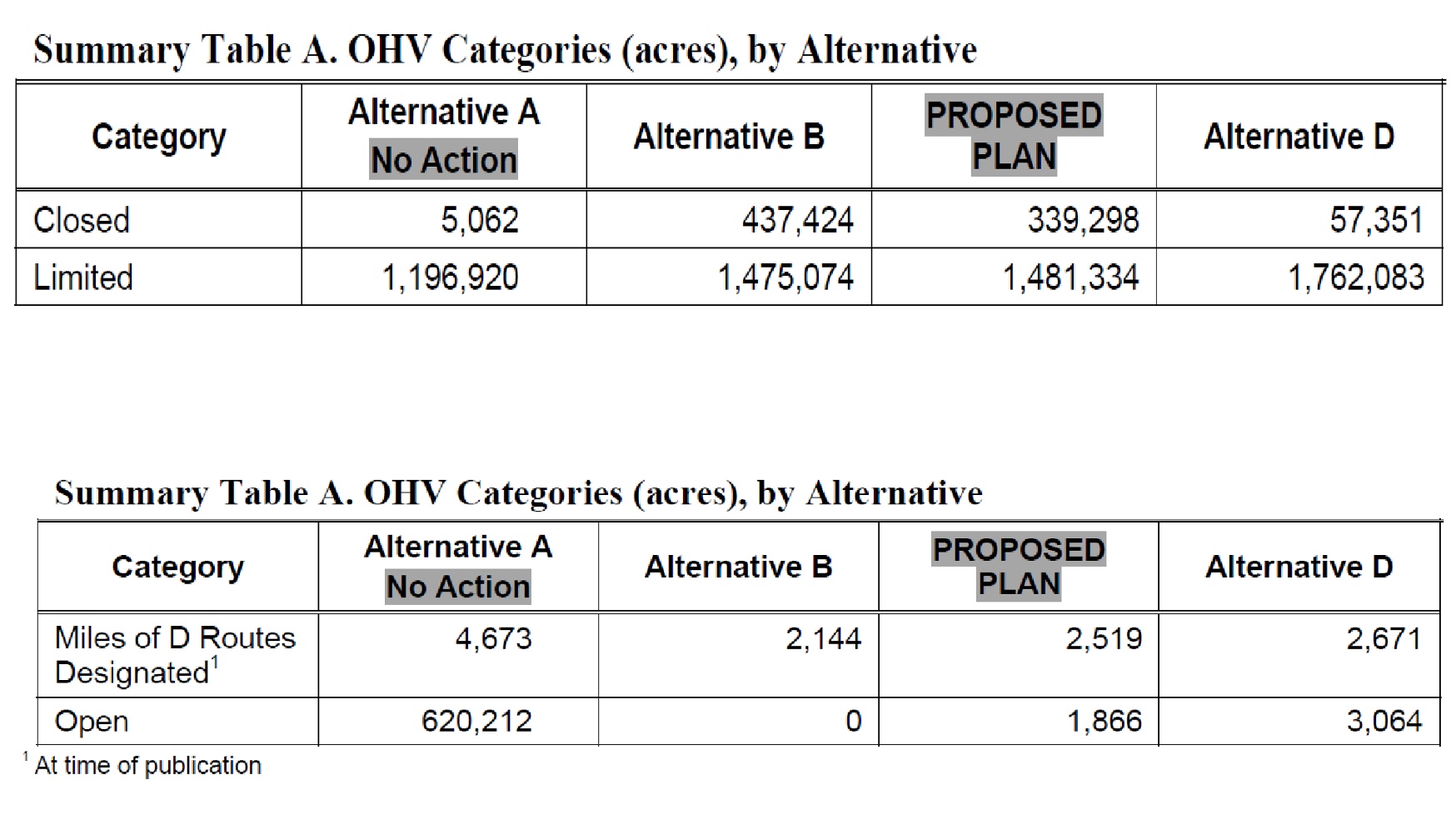

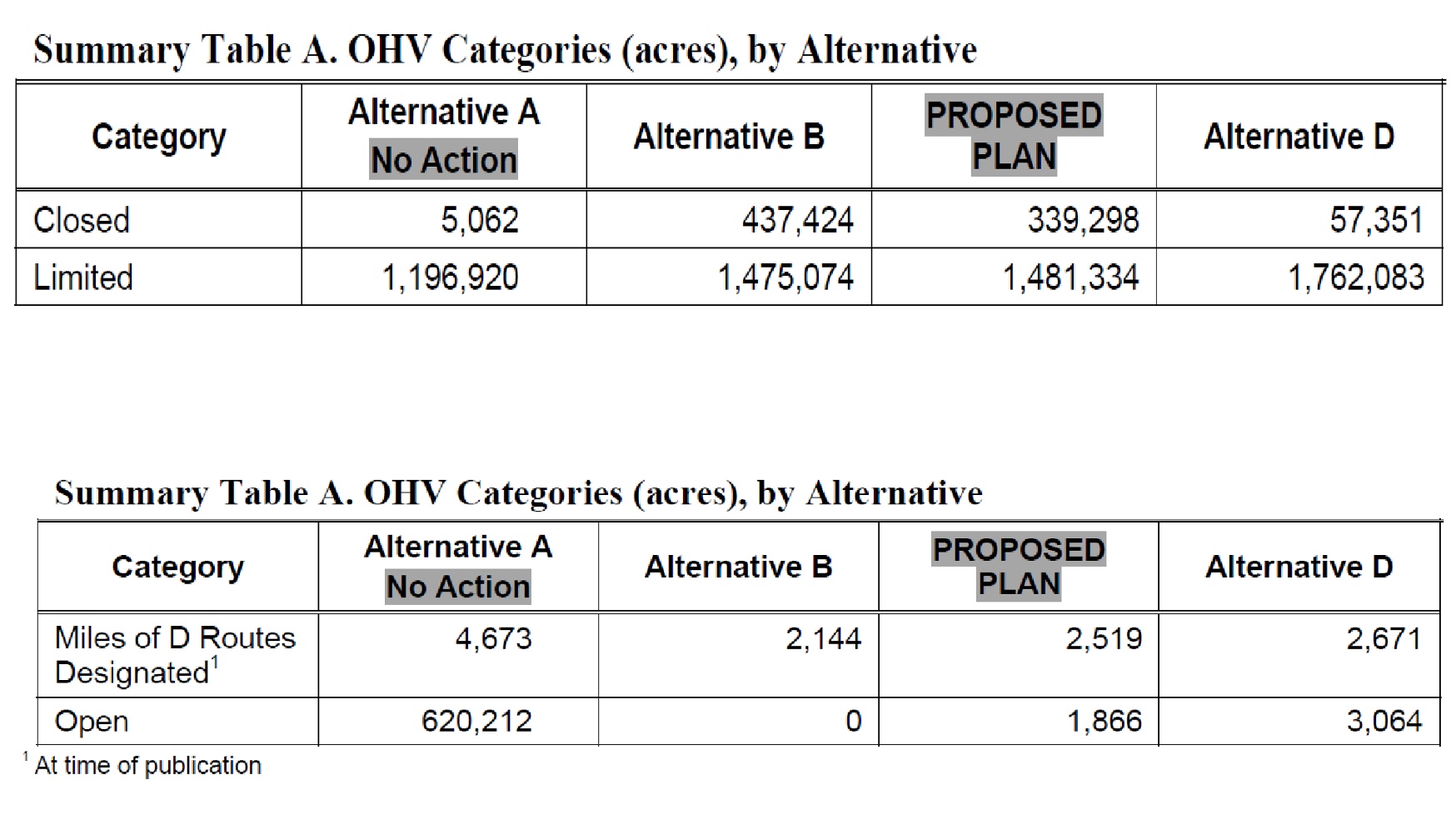

The RMP summarizes the significant scale of closures as part of the RMP process completed in 2008 is as follows:

[15]

[15]

The impacts of these acres of closures are significant on the designated routes on the Moab FO which the FEIS generally summarized as follows:

Impacts on resources and user groups would be similar to Alternative B, except that the adverse impacts to motorized users would be reduced by limiting OHV travel to designated routes within 4,481,334 acres along with 3653 miles of Band D class routes. 123 miles of singletrack routes with 1866 acres open to cross country travel.[16]

The FEIS summarized the scope of these closures as follows:

This alternative has 339,298 acres closed to OHV use, which is approximately 67 times more than under Alternative A.[17]

An accurate summary of recreational opportunities on the Moab FO since 2008 would be there have been a 67 times expansion of acres closed in the area and more than 40% of routes have been closed. Over the same time visitation to the area has at least doubled. Given these factual conclusions, any assertion of a factual basis for the range of alternatives provided is unfounded and must be meaningfully addressed. Planning should address how this vision has impacted the ability to find recreational opportunities in the area and how the decision aligns with the Moab RMP.

9(a). NEPA mandates detailed statements of high quality information for all decisions made in the planning process.

Prior to addressing the Organizations’ more specific concerns on specific legal issues in the Proposal, the Organizations believe a brief review of NEPA requirements provided in regulation, various implementation guides and relevant court rulings is warranted to allow for comparison of analysis provided in the Proposal and the proper standard. The Organizations believe that the high levels of quality analysis that are required by these planning requirements frequently get lost in the planning process. The lack of documenting the cause-and-effect relationship between management changes and impacts that will result, is a significant weakness in the Proposal. This should be remedied in supplemental works to detail how impacts are related to changes and these subsequent planning efforts must be provided a full and complete public comment process. Meaningfully analyzing this cause-and-effect relationship will result in significant changes to the preferred alternatives proposed in supplemental works.

At the landscape level of discussion, the NEPA regulations require any NEPA efforts to provide all information under the following standards:

… It shall provide full and fair discussion of significant environmental impacts and shall inform decision makers and the public of the reasonable alternatives which would avoid or minimize adverse impacts or enhance the quality of the human environment…. Statements shall be concise, clear, and to the point, and shall be supported by evidence that the agency has made the necessary environmental analyses….[18]

The regulations included the development of the Council of Environmental Quality, which expands upon the detailed statement theory for planning purposes as follows:

You must describe the proposed action and alternatives considered, if any (40 CFR 1508.9(b)) (see sections 6.5, Proposed Action and 6.6, Alternative Development). Illustrations and maps can be used to help describe the proposed action and alternatives.[19]

These regulations clearly state the need for the quality information being provided as part of this relationship as follows:

The CEQ regulations require NEPA documents to be “concise, clear, and to the point” (40 CFR 1500.2(b), 1502.4). Analyses must “focus on significant environmental issues and alternatives” and be useful to the decision-maker and the public (40 CFR 1500.1). Discussions of impacts are to be proportionate to their significance (40 CFR 1502.2(b)).[20]

The Proposal fails to account for the fact visitation has doubled and fails to provide any additional opportunities for the increased usage. Not only does the Proposal adopt a “no new trails” posture from the beginning, the Proposal provides for no expansion, even parking or toilets. No discussion exists in the Proposal as to why the closures are needed or why the specific standard is necessary. This full and fair discussion of many issues has not been provided in the Proposal and associated documents. As more specifically addressed in later sections of the comments, the range of alternatives for multiple use access to the Proposal is unacceptable. Many of the assumptions that are provided in the Proposal simply have no factual basis as outlined previously.

9(b). NEPA is designed and intended to stimulate public involvement and scrutiny.

The association of impacts from changes proposed to the management issue, is a critical component for developing public comments and involvement, because frequently members of the public do not have sufficient time, resources or understanding to make these connections. These concerns are summarized in the NEPA regulations which clearly provide the reason for the need for high quality information to be provided in the NEPA process. NEPA regulations provide as follows:

(b) NEPA procedures must insure that environmental information is available to public officials and citizens before decisions are made and before actions are taken. The information must be of high quality. Accurate scientific analysis, expert agency comments, and public scrutiny are essential to implementing NEPA.[21]

The Proposal does not provide a scientific or expert basis for many of the factual assumptions and positions therein, making them indefensible as they conflict with factual statements in prior NEPA matters.

NEPA analysis is supposed to stimulate public involvement and comment as part of federal planning actions. This is woven throughout the NEPA regulations and the agency implementation documents. For example, the BLM Planning manual states:

The CEQ regulations also require that agencies “make diligent efforts to involve the public in preparing and implementing their NEPA procedures” (40 CFR 1506.6(a)).[22]

Yet high quality information on numerous issues is missing in the Proposal, thus forcing the Organizations to theoretically address numerous issues despite their asserted priority and importance. This lack of high quality information frustrates the Organizations’ ability to meaningfully and completely comment on a variety of issues. Given that the Organizations have actively participated in countless NEPA analyses across the country, we struggle to understand the Proposal. Surely the overall public is negatively affected by poor quality data and analysis in the Proposal.

The Proposal does not address any new information developed since the litigation and 2008 RMP. The Proposal often asserts it is in compliance with the RMP but fails to support these assertions with analysis. The Proposal does not identify what the many issues are. Many users say they feel frustrated in reviewing the plan. They say that despite hours of review they cannot understand or explain what the management issue is in a particular area or why a particular route is being closed. The Proposal’s failure to provide such information makes it hard for any member of the public to comment thereon. Hence the frequent and vigorous opposition to the Proposal voiced by a wide range of user groups.

The Proposal’s overlooking numerous foundational documents and guidelines has improperly misdirected the range of alternatives. Given the foundational nature of the overlooked documents, the Proposal should be withdrawn to allow these foundational documents to be completely and accurately included in the Proposal inception.

9(c). NEPA requires that issues be addressed with high quality information and analysis.

Numerous issues have not been sufficiently analyzed to satisfy NEPA planning requirements. Much of the Proposal is disorganized and merely summarizes national planning guidance documents. Mere summaries of planning regulations will not satisfy NEPA requirements for a detailed statement of high quality information regarding why a decision was made.

The general standards for NEPA analysis of issues are as follows:

Agencies shall focus on significant environmental issues and alternatives and shall reduce paperwork and the accumulation of extraneous background data. Statements shall be concise, clear, and to the point, and shall be supported by evidence that the agency has made the necessary environmental analyses. An environmental impact statement is more than a disclosure document. It shall be used by Federal officials in conjunction with other relevant material to plan actions and make decisions.[23]

The US Supreme Court has applied these standards to conclude as follows:

Agency action is arbitrary and capricious if an agency “has relied on factors which Congress has not intended it to consider, entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem, offered an explanation for its decision that runs counter to the evidence before the agency,” or the agency action “is so implausible that it could not be ascribed to a difference in view or the product of agency expertise.”[24]

The Proposal does not meet the Supreme Court’s standard of review. The Proposal disregards many factors Congress specifically identified for NEPA review and analysis, despite the availability of information necessary to do this. The Proposal encompasses over 200 pages without any meaningful discussion of economic and travel management issues, both of which have received significant public input since scoping of the Proposal. Merely referencing the BLM LUP handbook and asserting compliance therewith is facially unacceptable for any proposal. NEPA requires a discussion of how the national standards were applied in the field office management decisions regarding specific areas, resource concerns and other field office specific management concerns. That has not occurred for economic and travel related issues.

9(d). NEPA requires a balance of uses and addressing of cumulative impacts.

As previously noted, NEPA requires a detailed statement of why a decision or alternative was chosen over other alternatives for resolving the challenge that is the basis of the NEPA analysis. The detailed statement is required on a wide range of topics, some of which often conflict. But this does not absolve managers from making the analysis or forming the Proposal to avoid difficult factual questions or avoid discussions of the failures in the NEPA analysis. One of NEPA’s fundamental goals is to:

promote efforts which will prevent or eliminate damage to the environment and biosphere and stimulate the health and welfare of man.[25]

As more completely addressed later in these comments, the Organizations have serious concerns that the welfare of man, more specifically the economic welfare of man, has not been properly addressed in the planning process. The Organizations believe the Proposal falls well short of stimulating the welfare of the residents that live in the local communities.

NEPA further requires that cumulative impacts be taken into account as follows:

Cumulative impacts can result from individually minor but collectively significant actions.[26]

The Organizations believe these cumulative impacts can take many forms, including not only addressing cumulative impacts to the environment but also addressing the cumulative impacts of the decisions made on a site-specific basis as part of the landscape level planning process. A cumulative impact that is simply never addressed in the Proposal is the fact that the visitation has doubled in the last decade to the planning area. In 2008, the RMP closed approximately 40% of the motorized routes in the area. This Proposal has alternatives that propose to close another 40% of the routes in the planning area, despite requirements in the RMP to provide quality recreational experiences on the Moab FO, and numerous site-specific development requirements as well. Cumulative impacts of exclusions in the analysis of specific factors must also be properly addressed in order to ensure that recreational opportunities are provided into the future as well. This has not occurred. There are numerous conflicts between the Proposal and Federal Law and regulation that is sought to be applied. An example is seen in applying the NTSA to prohibit protected uses of the Old Spanish Trail in favor of grazing interests that might be in the area. The cumulative impacts of these decisions have not been reviewed, which has resulted in conclusions being reached in the planning process that are in conflict with research from federal, state, and user group research.

9(e). Relevant Court rulings addressing NEPA standards directly apply to the NEPA regulations.

A brief summary of the standards that are applied by Courts reviewing agency NEPA analysis is relevant to this discussion, as the Courts have consistently directly applied the NEPA regulations to agency proposals. Relevant court rulings have concluded:

an EIS serves two functions. First, it ensures that agencies take a hard look at the environmental effects of proposed projects. Second, it ensures that relevant information regarding proposed projects is available to members of the public so that they may play a role in the decision making process. Robertson, 490 U.S. at 349, 109 S.Ct. at 1845. For an EIS to serve these functions, it is essential that the EIS not be based on misleading economic assumptions.[27]

Other courts have summarized this standard as follows:

[E]nsure that federal agencies have sufficiently detailed information to decide whether to proceed with an action in light of potential environmental consequences, and [to] provide the public with information on the environmental impact of a proposed action and encourage public participation in the development of that information. [28]

As previously addressed, The Proposal has not stimulated public involvement, nor does the Proposal show that a hard look has not been performed. The high levels of frustration expressed from the public in response to the release of the Proposal speaks to the quality of information provided and the ability of the public to comment on the information. Managers have not provided consistent information to the public regarding routes that are open and closed under each alternative. This portends serious difficulties for the agency in case of any court challenge.

10. The Proposal’s range of alternatives is unacceptably slanted, because many issues have not been sufficiently analyzed.

The lack of integration between expected recreational usage in the planning area and resources to be provided for that usage after implementation, is evidenced in the very limited range of alternatives that are provided in the Proposal. The Proposal closes motorized routes to the public for recreational usage even under the most development intensive alternative.. As previously noted, the Proposal summarizes all resource management issues, such as air, water and soil health, as good to excellent currently, making a minimum closure under every alternative difficult to understand at best.

It is well established that NEPA regulations require planning to provide all information under the following standards:

… It shall provide full and fair discussion of significant environmental impacts and shall inform decision makers and the public of the reasonable alternatives which would avoid or minimize adverse impacts or enhance the quality of the human environment…. Statements shall be concise, clear, and to the point, and shall be supported by evidence that the agency has made the necessary environmental analyses….[29]

The regulations included the development of the Council of Environmental Quality, which expands upon the detailed statement theory for planning purposes:

You must describe the proposed action and alternatives considered, if any (40 CFR 1508.9(b)) (see sections 6.5, Proposed Action and 6.6, Alternative Development). Illustrations and maps can be used to help describe the proposed action and alternatives.[30]

These regulations clearly state the need for the quality information being provided as part of this relationship as follows:

The CEQ regulations require NEPA documents to be “concise, clear, and to the point” (40 CFR 1500.2(b), 1502.4). Analyses must “focus on significant environmental issues and alternatives” and be useful to the decision-maker and the public (40 CFR 1500.1). Discussions of impacts are to be proportionate to their significance (40 CFR 1502.2(b)).[31]

A reasonable range of alternatives has not been provided here. The Proposals failure to tie proposed changes to numerous basic assumptions, (such as the assertion that there is no need for more trail) has resulted in the public not being adequately informed about many viable options for management. These analysis flaws have resulted in a range of alternatives that bears no rational relationship to the planned recreational usage or local community benefits from that usage. Ditto as to possible impacts to these communities from usage changes.

Providing an accurate and reasonable range of alternatives to the public as part of the NEPA process is a critical component of the NEPA process. The rational decision-making process of NEPA is compromised when agencies consider only a limited range of alternatives to their proposed projects.[32] When reviewing ranges of alternatives provided in a NEPA analysis, the Courts have consistently held:

The alternative section is ‘the heart of the environmental impact statement,‘ 40 C.F.R. 1502.14; hence, ‘[t]he existence of a viable but unexamined alternative renders an environmental impact statement inadequate.[33]

When determining if a NEPA effort has provided a satisfactory range of Alternatives, Courts have held the proper standard of comparison is to compare the purpose and intent of the NEPA effort to the Range of alternatives provided. Other Courts have summarized this legal requirement as follows:

Irreparable damage may in the context of an action to enforce NEPA be implied from the failure by responsible authorities to evaluate fully the environmental impact of the proposed project, and consider alternative proposals before engaging in a project which constitutes major federal action.[34]

Given the numerous documents created by the Moab FO clearly providing a contrary direction for the management areas and guidelines that have been overlooked in the creation of the Proposal, the Organizations believe these failures have caused a range of alternatives to be presented that are significantly different from the range of alternatives that would have been presented if many priority concerns had been accurately addressed when the original vision for the Proposal was created. Given the foundational nature of these documents, the travel management portion of the plan should be withdrawn to allow for complete and accurate inclusion of these foundational documents in the creation of the Proposal.

11(a). The economic analysis provided with the Proposal is incorrect on its face.

NEPA analysis also requires a meaningful review of the possible economic impacts to local communities from the Proposal. Prior to addressing more specific NEPA related concerns involved in the Proposal, a brief summary of the inherent complexity of any economic analysis is warranted. Economic contribution calculations are often complex and involve a balance of numerous factors that directly impact the spending habits of those sought to be studied, and often involve far more analysis and discussion than planning for endangered species. The basic complexity of any economic determinations and the size of the calculations to be made are summarized by the Western Governors’ Associations’ recreational economic contributions study as follows:

How is “economic impact” calculated? Many people might think of a consumer buying equipment – a tent, fishing pole, ATV, bicycle, boat, snowboard or rifle. However, the impact is much more complex than the manufacture and sale of gear and vehicles. Gas stations, restaurants, hotels, river guides and ski resorts benefit from outdoor recreation. In total, equipment and travel expenditures represent billions in direct sales that create jobs, income, tax revenues and other economic benefits.[35]

The complexity of the calculations undertaken for economic impact calculations is immediately evidenced by the number of pages required in most economic impact reports, as the explanation of the analysis process used to arrive at any final figure of any economic contribution analysis is often as valuable as the total economic contribution that is reached.

The basic mandate to include documented economic analysis early in the interdisciplinary team process for public lands planning is provided by the Federal Lands Planning and Management Act (“FLPMA”). FLPMA specifies the various criteria that must be incorporated at specific times in the development of a land use plan as follows:

(c) In the development and revision of land use plans, the Secretary shall–

(2) use a systematic interdisciplinary approach to achieve integrated consideration of physical, biological, economic, and other sciences;[36]

The basic mandate of FLPMA regarding the critical need for documented economic analysis is more specifically and extensively addressed in Appendix D of the BLM’s Land Use Planning Handbook. Appendix D opens as follows:

“A. The Planning Process

To be effective, social scientific data and methods should be integrated into the entire planning process, from preparing the pre-plan to implementation and monitoring. The main social science activities for the various planning steps are outlined in Table D-1.

| Table D-1. —Social science activities in land use planning

Planning steps |

Social science activities |

| Steps 1 & 2—Identify Issues and Develop Planning Criteria |

▪ Identify publics and strategies to reach them

▪ Identify social and economic issues

▪ Identify social and economic planning criteria |

| Step 3—Inventory Data |

▪ Identify inventory methods

▪ Collect necessary social and economic data |

| Steps 4—Analyze Management Situation |

▪ Conduct social and economic assessment, including existing conditions and trends and the impacts of continuing current management

▪ Document assessment methods in an appendix or technical supplement |

| Step 5—Formulate Alternatives |

▪ Identify social and economic opportunities and constraints to help formulate alternatives |

| Step 6—Estimate Effects of Alternatives |

▪ Identify analysis methods

▪ Analyze the social and economic effects of the alternatives

▪ Document impact analysis methods in an appendix or technical supplement

▪ Assess mitigation opportunities to enhance alternatives’ positive effects and minimize their negative effects |

| Steps 7 & 8—Identify Preferred Alternative and Finalize Plan |

▪ Identify potential social and economic factors to help select the preferred alternative |

| Step 9—Monitor and Evaluate |

▪ Track social and economic indicators“[37] |

Tellingly, economic concerns are the only factor addressed by the BLM planning handbook for every step of the planning process. Documentation of economic forecasts and analysis methodology is required in two separate stages before release of draft alternatives. The required documentation of these concerns is exactly the information the Organizations are seeking to review but are unable to review. This lack of analysis of economic concerns has become even more apparent in the Organizations’ attempt to analyze economic concerns given the scope of inconsistency of the Proposal findings with the research works of any other federal, state, local, or user groups.

As a result of the facial inconsistencies between Proposal conclusions and all other available economic research, the Organizations sought to review the documentation on the process used to analyze economics, such as testing protocols, reviews of outside research materials, sampling of user groups and other factors involved in economic analysis. This documentation is specifically required to be developed in Step 4, 5, and 6 of the process identified in the Handbook. This information is not provided or mentioned at all in the Proposal.

The Proposal fails to meaningfully address possible economic impacts of the Proposal, as basic foundational analysis points. Comparative spending profiles and estimates for visitation to the area are patently incorrect. The Spending profile for recreational users provided by the Proposal is incorrect simply in that it asserts all recreational users spend similar amounts recreating in the area. The Proposal identifies this cornerstone of analysis as follows:

Spending profiles for OHV visitors are similar to the overall spending profiles that the Moab BLM has developed for all recreation visitation to Moab BLM.[38]

Not a single study supports this assertion as far as the Organizations are aware. All research known to us concludes that motorized users spend sometimes as much as 5 times more than other recreational users. Many recreational users rent equipment in Moab, these rental fees average at least $300 per unit per day, and many people rent multiple units. On top of that, taxes for rental vehicles in Moab are 15-19%, while taxes for rental non-motorized gear are under 9%.

A brief analysis of relevant court rulings on the quality and accuracy of economic analysis NEPA is helpful, as these standards are the benchmark for comparison. The Courts have held:

an EIS serves two functions. First, it ensures that agencies take a hard look at the environmental effects of proposed projects. Second, it ensures that relevant information regarding proposed projects is available to members of the public so that they may play a role in the decision making process. Robertson, 490 U.S. at 349, 109 S.Ct. at 1845. For an EIS to serve these functions, it is essential that the EIS not be based on misleading economic assumptions.[39]

The Court then discussed the significance of economic analysis in planning as follows:

Misleading economic assumptions can defeat the first function of an EIS by impairing the agency’s consideration of the adverse environmental effects of a proposed project. See, South La. Envtl. Council, Inc. v. Sand, 629 F.2d 1005, 1011-12 (5th Cir.1980). NEPA requires agencies to balance a project’s economic benefits against its adverse environmental effects. Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Comm. v. United States Atomic Energy Comm’n, 449 F.2d 1109, 1113 (D.C.Cir.1971). The use of inflated economic benefits in this balancing process may result in approval of a project that otherwise would not have been approved because of its adverse environmental effects. Similarly, misleading economic assumptions can also defeat the second function of an EIS by skewing the public’s evaluation of a project.[40]

The Court in the Hughes River decision invalidated an EIS based on an error in economic contribution calculations of approximately 32%. The current Proposal contains an error in economic calculations that is more than twice the 32% found sufficient in Hughes River to overturn the EIS in that matter.

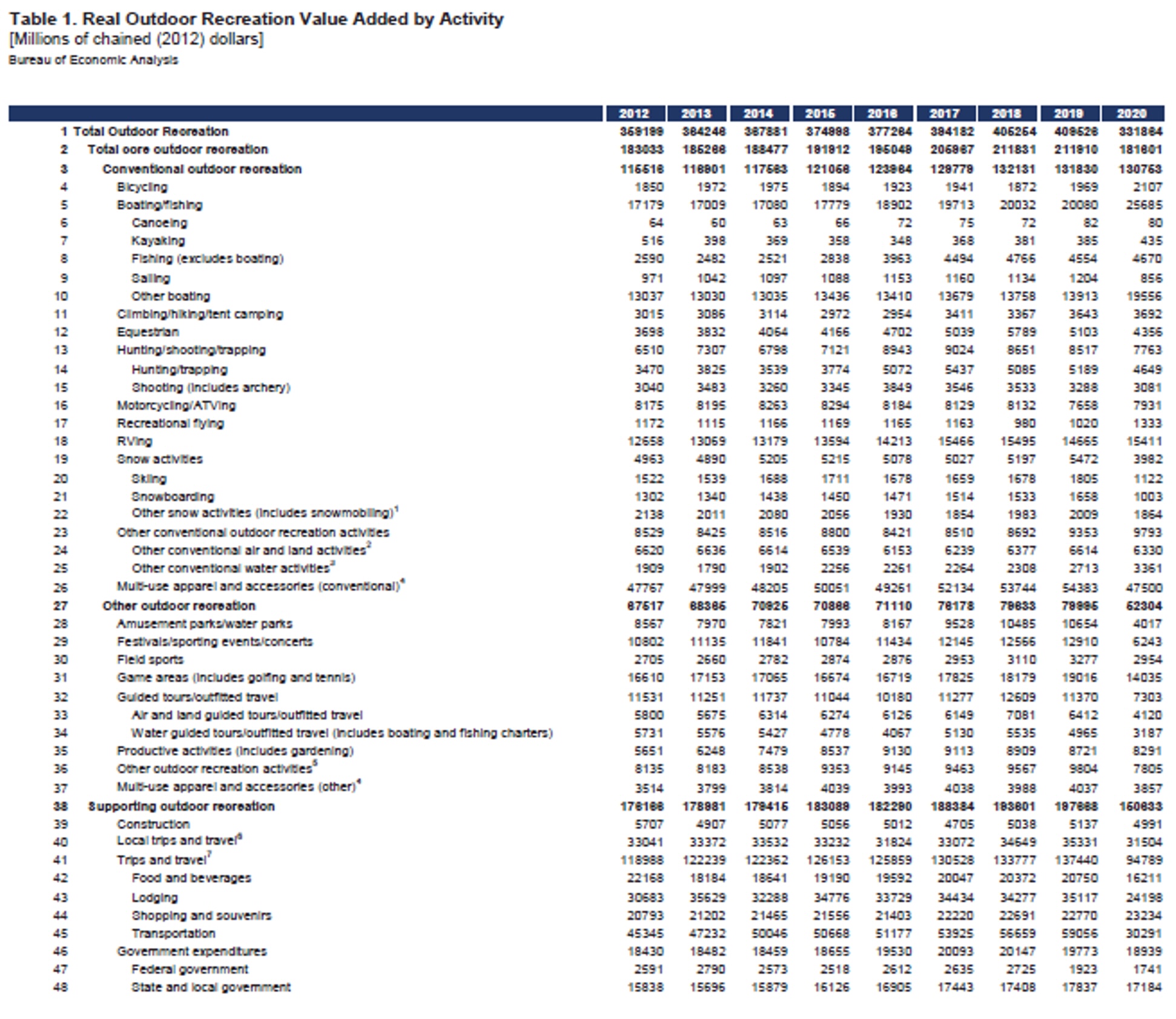

11(b)(1). The US Department of Commerce has repeatedly and specifically concluded that recreational economics are driven by motorized spending.

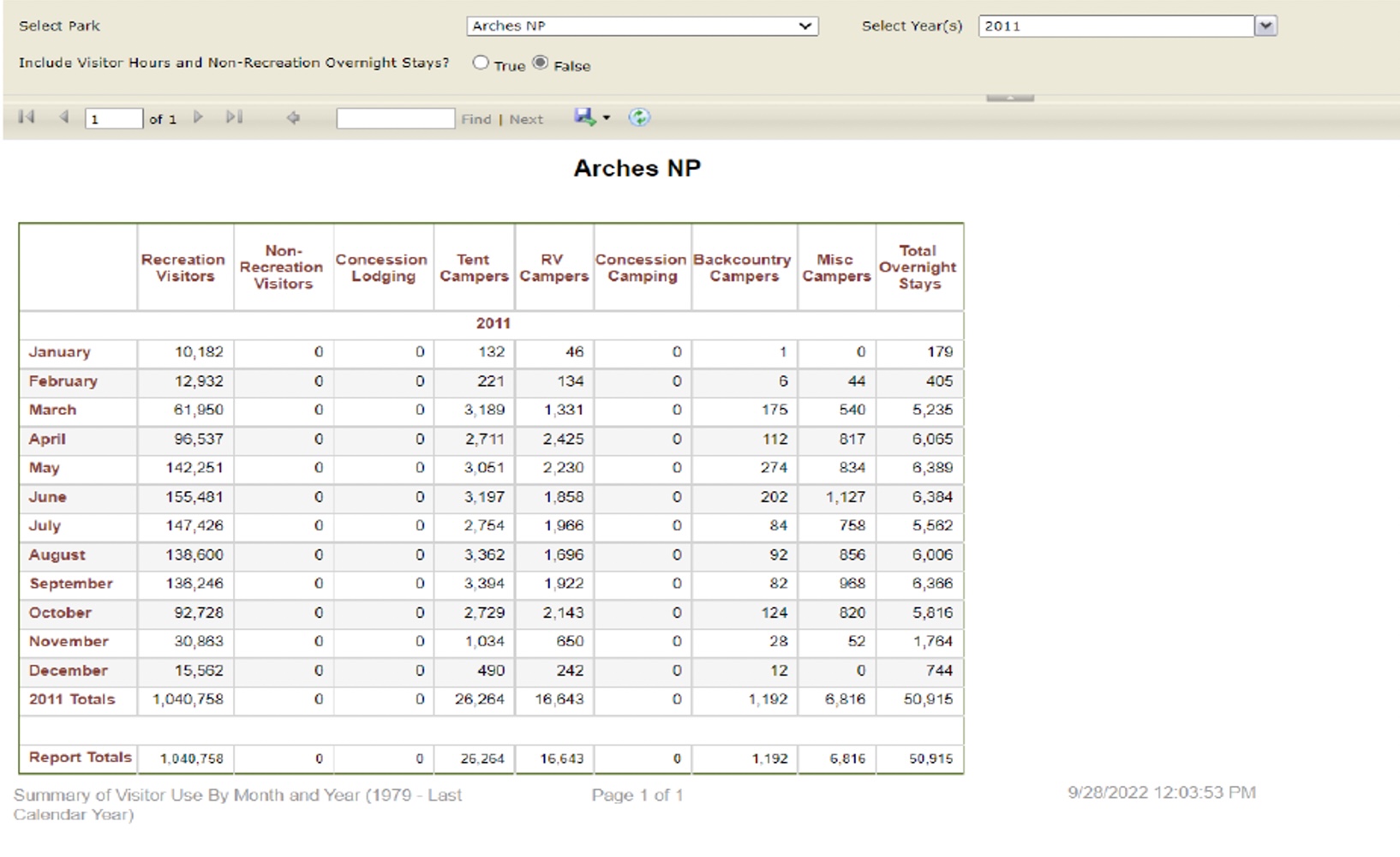

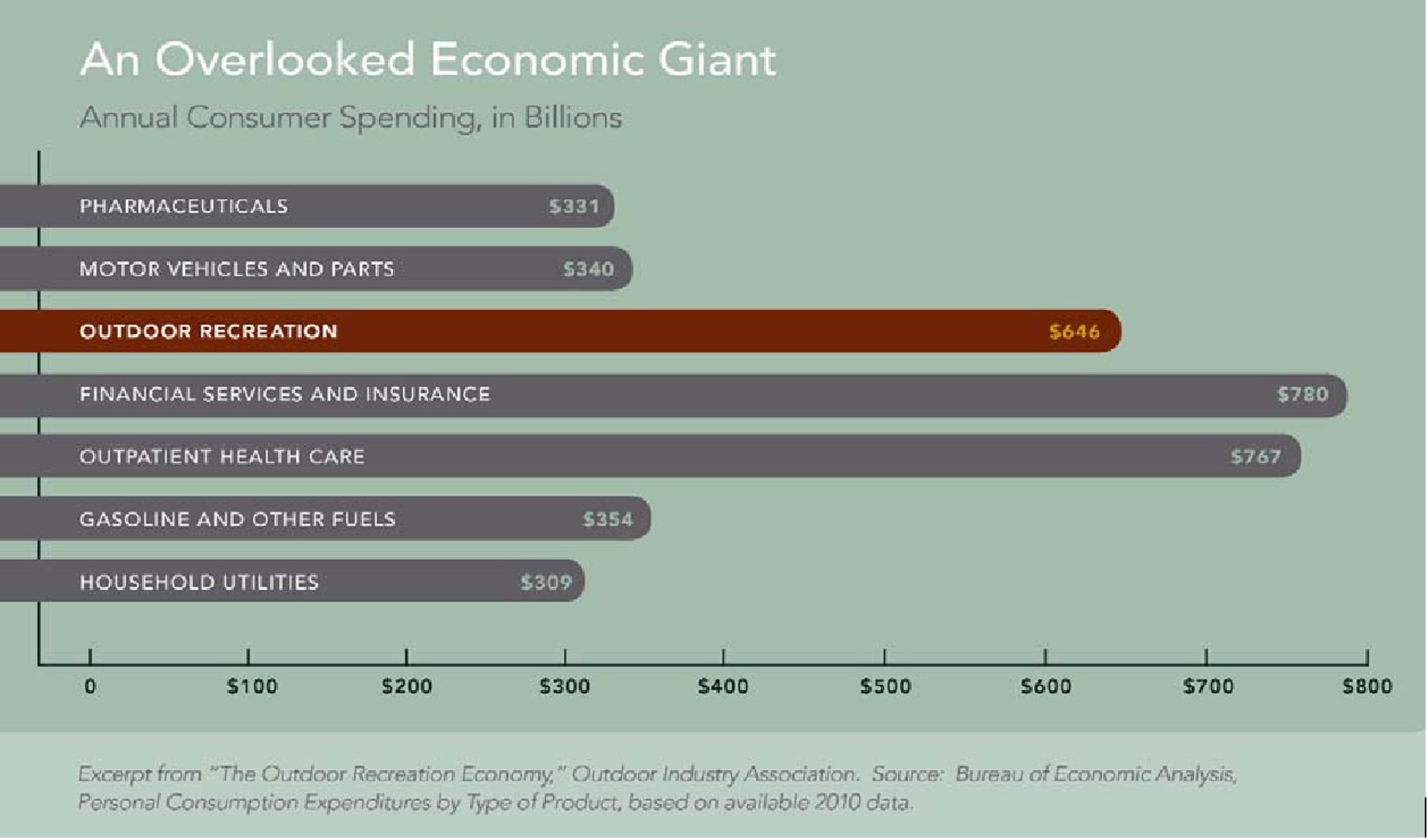

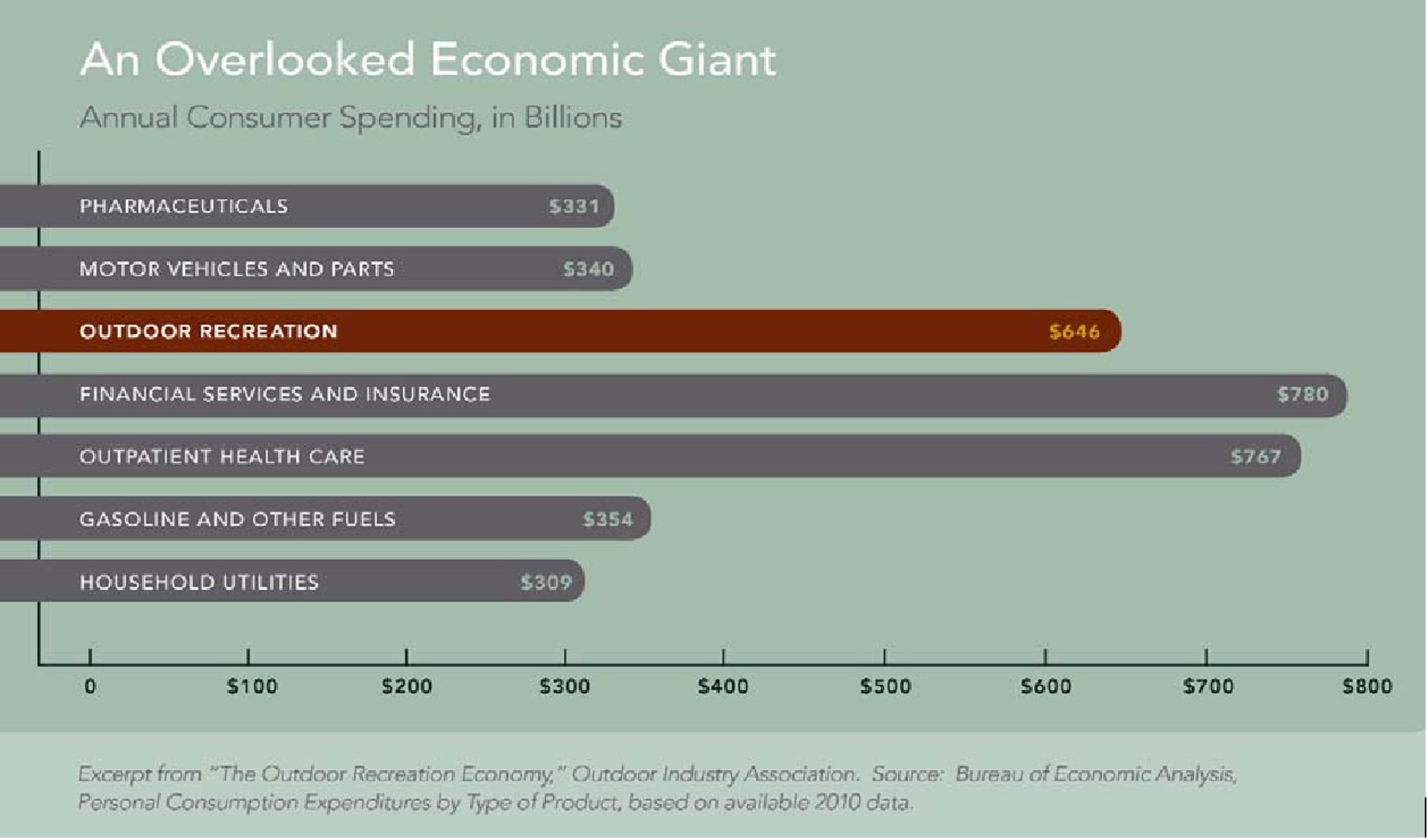

The availability of high-quality economic contribution data for recreational activities has recently been greatly expanded as the Department of Commerce has undertaken a 5-year state by state analysis of recreational spending that ended in 2021. Department of Commerce research commissioned by Secretary of Interior Sally Jewel to determine the value of outdoor recreation as part of the Gross Domestic Product was released. The research identified that outdoor recreation accounted for 2% of the GDP or more than $371 Billion in spending annually and that this value was steadily increasing from 2012 to 2016. This research further concludes that motorized spending was the dominant portion of spending for recreational activity, and almost exceeded all other spending sources combined. This research provides the following breakdown of the total recreational spending: [41]

The above chart from the Department of Commerce study indicates that motorized spending is occurring at a rate 6 times higher than all other recreational activities. The Proposal’s patent conflict with this conclusion is highly problematic.

At the conclusion of the Department of Commerce research period, they provided spending conclusions for numerous different user groups for the 8-year period that they were able to research. These conclusions are as follows:[42]

These motorized travel related economic conclusions show even more problems for the Proposal at the landscape level, as indications are that OHV and Motorized camping outspend all other possible recreational activities in the planning area, combined. OHV recreation alone comprised almost 3 times more spending than the hiking and tent camping category and almost 2 times the cycling category. This disparity only increased when RV camping was included in the analysis.

Given this clear and unequivocal demonstration of values to communities from motorized recreational uses, it is not reasonably arguable that the Proposal sufficiently analyzes these points. These failures of analysis are even more immediate when compared to the high-quality peer-reviewed analysis of the economic benefits from motorized recreation.

11(b)(2).The Western Governors’ Association recently concluded that recreational spending is the driver for western economies.

Recreational usage of public lands is a significant portion of the Moab economy, especially in the smaller mountain communities that have already lost more traditional sources of revenue, such as timber, farming and mining. This is only more compounded by the fact that Moab has marketed itself as a global destination for recreation for decades. The critical nature of recreational economics to the western economies was recently highlighted in the Western Governors’ Association Get Out West report that specifically stated:

Spending on outdoor recreation is a vital part of the national and western economies. It means jobs and incomes and can be the lifeblood of many rural communities in the West. This snapshot helps highlight the value of this often-overlooked sector- one that is not otherwise measured as a traditional pillar of the US economy.[43]

Contrary to the huge value of recreational activity that has been identified by the Western Governors’ Association, recreational economics are only briefly addressed in a couple pages of the Proposal without analysis of what inputs were relied upon for development of these calculations. Given the limited analysis of economics, the Organizations are forced to analyze this issue on a very general level and believe that this analysis simply is not the detailed statement addressing high quality information that is needed for NEPA purposes.

The Western Governor’s Association provides a compelling summary of the value of the recreational activity for western states as follows:[44]

11(b)(3). Proper integration of economic information in the planning process is an ongoing requirement in federal land management planning.

The proper integration of accurate economic information is often a weakness of the public lands planning process, which has resulted in the creation of many other longer-term problems when decisions reflecting an imbalance of multiple uses are implemented. This concern was recently identified as a major planning issue that is not just limited to Utah. The Western Governors’ Association released its Get Out West report in conjunction with its economic impact study of recreation on public lands in the Western United States which specifically identified that proper valuation is a significant management concern as follows:

Several managers stated that one of the biggest challenges they face is “the undervaluation of outdoor recreation” relative to other land uses.[45]

The Get Out West report from the Western Governors’ Association also highlighted how critical proper valuation of recreation is to the development of good management plans based on multiple use principals. The Get Out West report specifically found:

Good planning not only results in better recreation opportunities, it also helps address and avoid major management challenges – such as limited funding, changing recreation types, user conflicts, and degradation of the assets. Managers with the most successfully managed recreation assets emphasized that they planned early and often. They assessed their opportunities and constraints, prioritized their assets, and defined visions.[46]

The Organizations believe our concerns regarding the Proposal and those expressed in the Western Governors’ Get Out West report virtually mirror each other. There can simply be no factual argument made that recreation has not been significantly undervalued in the Proposal and this has directed the range of alternatives provided for multiple use recreation on the Proposal. The Proposal should examine potential direct and indirect impacts of each alternative on the undisputed value of multiple use outdoor motorized recreation, if only to reflect the analysis provided by Western Governors Association. NEPA requires comparing the values of each use. That comparative analysis is missing in the Proposal.

11(c).US Forest Service National Visitor Use Monitoring spending profiles for recreation show a huge amount of diversity in spending profiles across user groups.

The Proposal asserts without basis that all recreational users have similar spending profiles.. This conclusion is incorrect as best available science clearly concludes that motorized users, who make up the heaviest impacted user group from the Proposal, are also the highest spending group of users who use business and economic opportunities provided in the Proposal area.

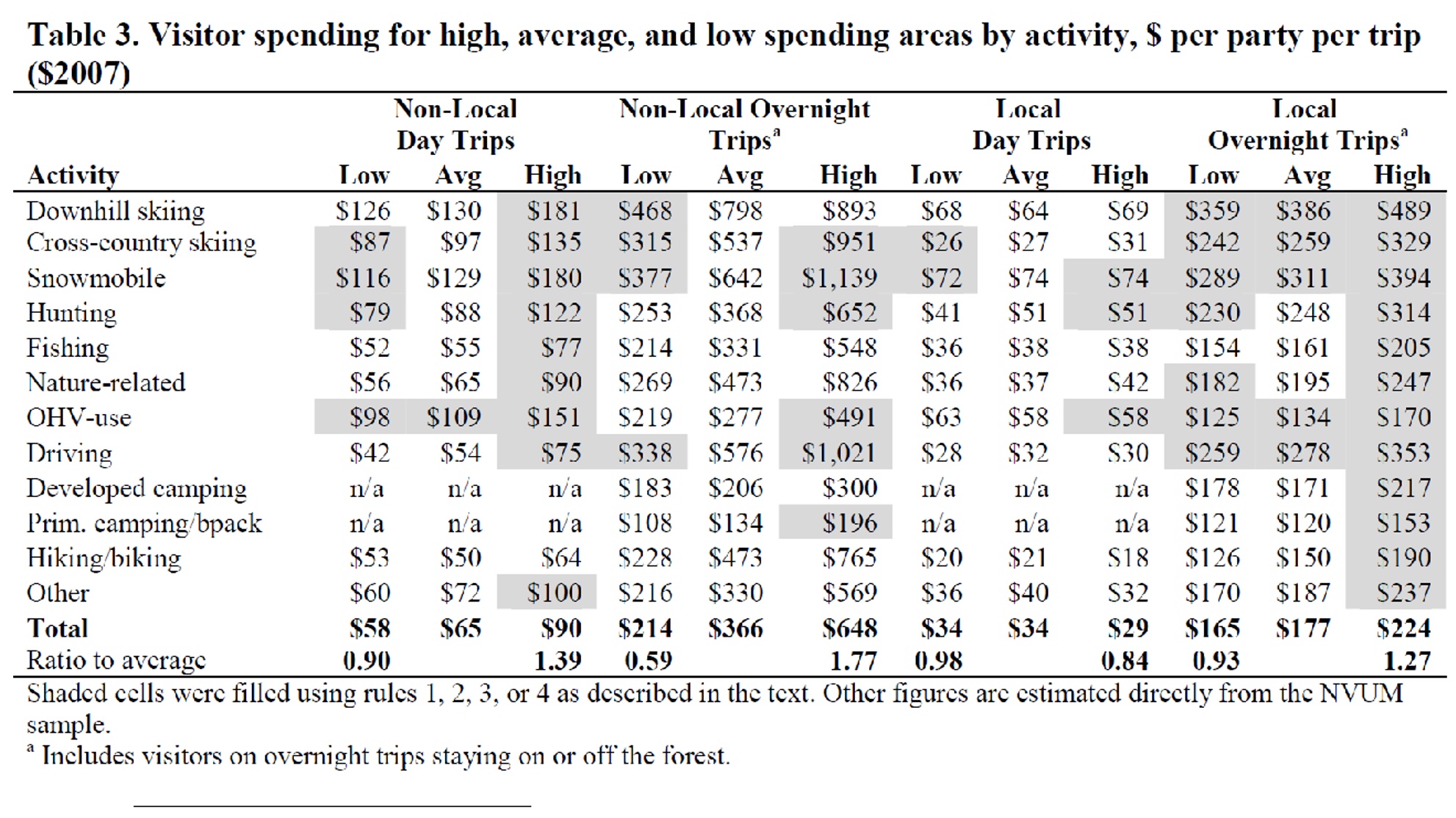

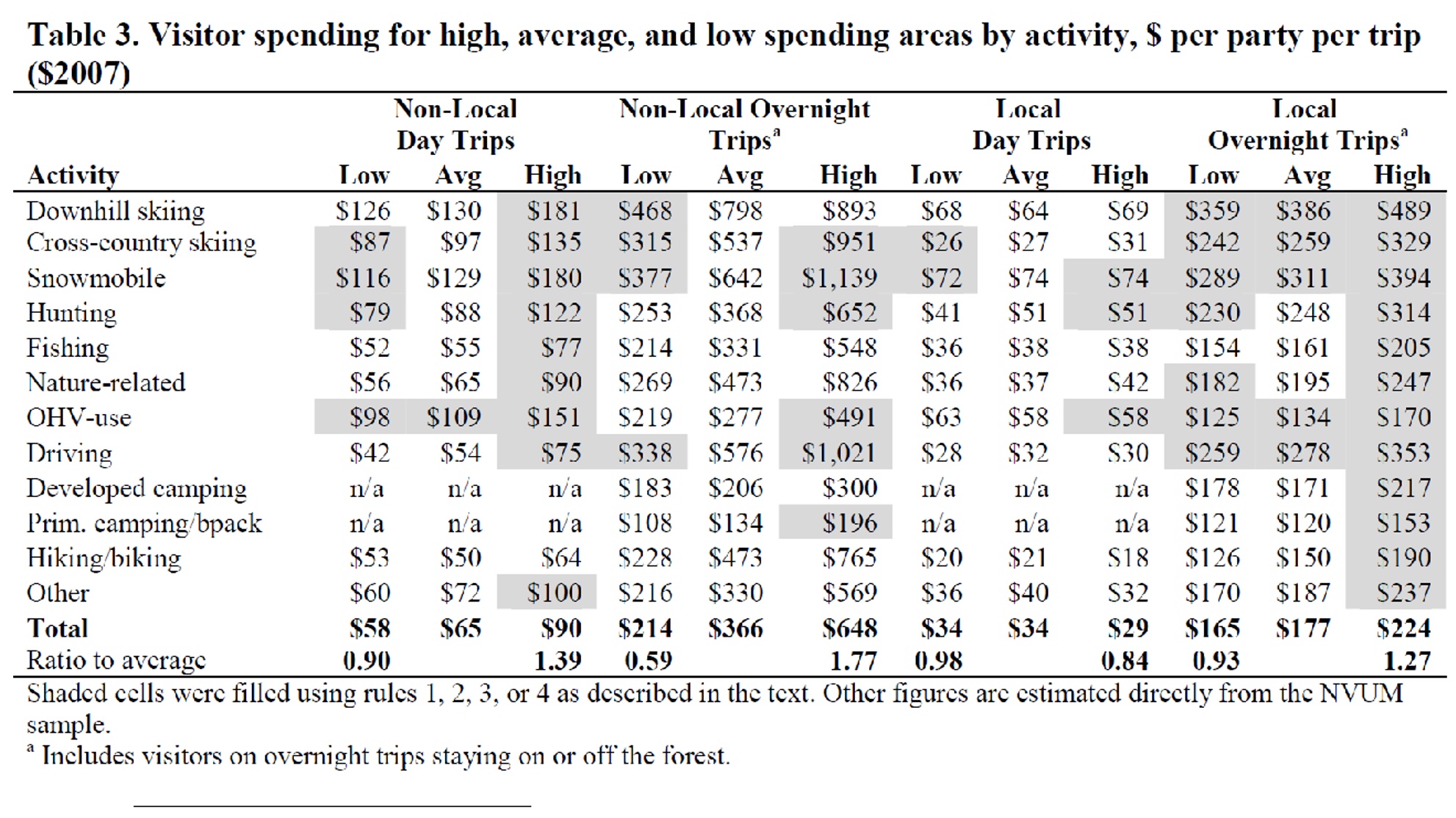

Contrary to the assertion in the Proposal, as part of the USFS efforts in the Visitor Use Monitoring efforts, the US Forest Service has provided hugely detailed analysis of the diversity of spending profiles of users as follows:[47]

The USFS research further concludes that the type and nature of visitation can hugely impact the spending profiles of the recreational community:

Within activities and trip types, the greatest observed spending was for non-local downhill skiers on overnight trips ($893). The lowest observed spending was for locals hiking or biking on day trips ($18)[48]

Given that the USFS has clearly identified that motorized users consistently spend more than twice what similar users spend, the conclusions of the Proposal are problematic both factually and legally. This simply must be corrected as this clearly identified the arbitrary nature of this assertion.

11(d).Non-Motorized recreation is not synonymous with entirely non-motorized area management.

The Organizations have provided detailed information regarding the significant imbalance of recreational spending when motorized vs. non-motorized activities are compared. Too often we have been told that non-motorized spending and non-motorized recreation are identical spending profiles and that non-motorized spends as much or more than motorized. Highly credible sources such as BEA and WGA and others have concluded very differently on this issue. Often the implications of this are lost if high quality economic analysis is not performed. As a result, negative economic impacts to communities from proposed OHV travel restrictions, are grossly underestimated.

It is encouraging to see that some economic analysis has started to recognize the huge role that motorized access provides even in non-motorized recreational activities. An example of this recognition is as follows:

“Quiet recreation” is recreation that does not involve significant motorized activity (such as motor-boating, snowmobiling, motorcycling, other off-highway-vehicle use, etc.)—aside from any transportation to and from the recreation sites. In this analysis, we estimate the number of “quiet recreation visits,” which are trips (of any length) to BLM lands managed by the CCFO in southwest Utah for the primary purpose of engaging in quiet recreation activities.[49]