CPW Commission

Submitted electronically

https://engagecpw.org/comment-form

Re: Wolf Reintroduction Plan

Dear CPW Commissioners:

The Organizations thank the Commission for this opportunity to provide public comment on the draft CPW Wolf Reintroduction Plan (Hereinafter referred to as “The Plan”). These comments are designed to supplement previous comments submitted on this issue. Our Organizations submit the Plan is a mixed bag of concepts – some we support and others we are concerned about and others we must oppose. The Organizations are very concerned that the Plan overly focuses on ranching and farming issues and is entirely silent on many other impacts, such as nonconsumptive recreation, that could be far more severe to the State over time. While we vigorously support full compensation of ranchers for any direct losses our Organization’s are very concerned about indirect impacts that have been addressed in similar efforts for similar species in the past and are not addressed in the Plan at all. The Organizations have chosen to provide our input via the written process rather than verbally simply due to the complexity of our concerns.

The Organizations are very concerned that any ambiguity, or silence in the Plan on particular issues will result in decades of ligation on any form of planning effort that may follow. Predominately CPW will not be involved or often times not even aware of these efforts. As an example, litigation continues over lynx management questions despite the fact CPW reintroduced the species more than 20 years ago and has declared that reintroduction a success. While CPW awareness of issues such as this may be low, these are impacts that must be mitigated with clear management guidance, even if guidance on the issue is that the particular issues is not a concern for the species. This can be hugely valuable in subsequent efforts as too many planning concerns for the lynx remain centered on the fact someone saw a lynx. Inserting a new predator into discussions such as this will not bring clarity to these other efforts.

We support the data that has been provided about the steady population history of all species and that many species are above population goals. We also support Plan recognition of the expected decline of deer and elk populations as a result of wolves and that it is expected to shorten hunting seasons. This will be a major concern moving forward for those in the consumptive recreational community. This is a significant improvement in the Plan when compared to the 2005 CPW wolf plan that was almost silent on this type of issue. While this is an improvement, we are also concerned that a lot of this data is buried in the middle of the plan and simply not easily found. While we are aware this is a wolf plan, this information on other species is critically important and should be made easier to find and more clearly stated.

While there are several portions of the Proposal that we can support, we must express significant concern over the lack of data and management guidance on dispersed nonconsumptive recreation in the Proposal.[1] This void of information falls well short of the clear guidance that CPW has partnered with USFWS in developing for other species, such as the wolverine. In the wolverine reintroduction discussions, CPW championed the inclusion of language that dispersed recreation was a minimal threat to the species in various plans and USFWS efforts. The failure of CPW to include guidance on this issue is disappointing and sends a strong message to the nonconsumptive recreational community that their concerns about possible impacts from the wolf reintroduction are not as significant or valued similarly to impacts to the consumptive community, which are detailed heavily in the Proposal. The optics on such a position are troubling and we hope are something that would just be quickly remedied as compared to the other issues involved in the wolf reintroduction, our remedy is easily provided and costs nothing to the state or CPW.

The Organizations are opposed to several provisions of the Plan where CPW assumes that land closures will be necessary for the protection of wolves. Absolutely no guidance or even discussion is provided on this issue in the Plan, nor is there any discussion of why resources such as the incremental management structure outline in the 2021 CPW Trails and Wildlife Guide would not be fully applicable to wolves. We would like to understand how this decision was made, what lands it applies to and how long the proposed closures will last. We are sure that other interests will want to understand what these closures will look like as well. We are vigorously and completely opposed to any closures of any lands for the benefit of the wolf without a clearly stated scientific basis for the closure and application of an incremental management structure as outlined in the Trails and Wildlife Guide has been applied.

The Plans silence on issues that have been historically addressed by CPW stands in stark contrast to the inclusion of mandatory management actions for concerns that many experts have identified as theoretical and academic in nature. These actions are addressing management concerns that simply are not occurring in wolves in the Western United States. One example of this concern would be the inclusion of genetic migration corridors for wolves. We are very concerned that this concept is only briefly mentioned and is poorly described and not analyzed in the Plan. While there are might concerns on this issue with Mexican Wolves isolated in Arizona, of wolves that are forced to live on an island in the middle of Lake Superior. Genetic diversity is an issue for isolated wolves outside the region. We believe that the Plan should remain focused on identifiable challenges for the Colorado wolf reintroduction and address novel or academic issues at some other time. We believe the concept of genetic corridors is an example of the novel or theoretical issues that we could be drawn into in subsequent planning and serves as an example of why generalized management clarity must be provided. The Colorado wolf plan should focus on Colorado Wolves and Colorado impacts.

1(a). The Organizations vigorously support the statements regarding ungulate species populations and expected impacts to those populations from wolves.

CPW holds broad authority to manage wildlife and recreation throughout the State and has proven that jointly created documents between CPW and federal land managers can carry great weight in subsequent planning efforts. CPW position in these documents has always been a desire for more ungulate and other populations. These jointly created high quality documents will be critical in the wolf reintroduction as this is the first CPW management action that is going to directly create a decline in ungulate populations in the State. The Plan also recognizes that in some areas this impact will be a significant decline. These clear statements of expected impacts from wolf reintroduction must remain in the Plan and be further highlighted and clarified to avoid future management issues and immense conflict between user groups.

CPW has a great story to tell regarding the successful management of wildlife species in Colorado, as most species are at or well above population goals and often at or above populations that were present in 1980. Our Organizations have worked hard with CPW and federal managers in furtherance of these goals and it is highly frustrating for us to have to address issues such as this. This is a huge success, but it is often simply not recognized in local discussions around wildlife populations. Too often we hear assertions that wildlife populations are collapsing and trails must be closed. As a result, the Organizations vigorously support the clarity of statements in the Plan regarding the current populations of deer, elk and other species in the state. The Plan provides the following statement on elk populations:

“Colorado’s statewide elk population peaked in 2001 and as of 2021 was estimated at 309,000 after hunting season. In 2004, antlerless license numbers were at their highest which helped reduce elk populations to Herd Management Plan population objectives. Since 2004, the statewide total elk population estimate has increased as a result of CPW reducing antlerless and either-sex elk licenses every subsequent year.”

The sum of Colorado’s post-hunt HMP population objective ranges for elk statewide is 252,000-306,000 for all 42 elk herds combined. These data indicate that Colorado’s elk population is over objective.”[2]

The Organizations are aware that in some areas of the state there are challenges being faced for elk and the Organizations believe these are generally local or regional issues that should be managed at that level. Recognition of the negative impacts of the wolf on those populations will be a major benefit in these subsequent local efforts.

The Plan also makes similar statements regarding the deer herd in the State:

“Mule deer populations in western Colorado have declined precipitously since the 1970s. CPW and the public have concerns over mule deer declines in the largest herds of western Colorado….Colorado’s statewide deer population declined from roughly 600,000 deer in 2006 to an estimated 416,000 post-hunt 2021. The statewide deer population has been more stable recently, averaging 420,000 over the last 11 years. There is on-going interest from various constituents to increase mule deer populations; however, for many deer herds, population management is largely dictated by herd productivity and performance, winter severity, and Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) prevalence.”[3]

The Organizations appreciate the Plan recognizing populations of deer are largely stable and the somewhat cautious manner the Plan uses to call for increases in wildlife populations as there are many factors causing the situation. It has been our experience that demands from special interests for more wildlife are becoming highly frequent and often made in a very public manner. In the last year, we are aware of numerous inaccurate articles on this issue being present throughout the state. As an example: The Durango Herald ran an article January 11, 2022[4] asserting a critical need for wildlife corridors to protect plummeting wildlife populations; the Durango Herald ran a second article asserting Wildlife numbers on the decline in Southwest Colorado and plummeting worldwide[5]; and the Colorado Spring Gazette Recently ran an article asserting wildlife populations were at an all-time low in the state.[6] The Organizations do not believe that these discussions will be easier or less common after the wolf reintroduction actually starts causing these populations to decline.

It is unfortunate to note that this erroneous narrative is already creeping into local planning documents despite current CPW efforts to provide accurate information on these issues. Other Organizations and collaborative planning efforts simply are getting wildlife estimates and trends wrong already and populations are strong and steady. As an example, Envision Chaffee County planning documents have already taken the position that ungulate populations are plummeting as follows:

“Summary

According to research, 8 of 13 key wildlife populations in Chaffee County — or 65% — are in steady decline. This includes bighorn sheep, down 29% since 2000; mountain goat, down 32% since 2000; and elk, down 11% since 2000. Detailed data provided by Colorado Parks and Wildlife and USFS biologists on these species is available in the Chaffee Recreation Report.”[7]

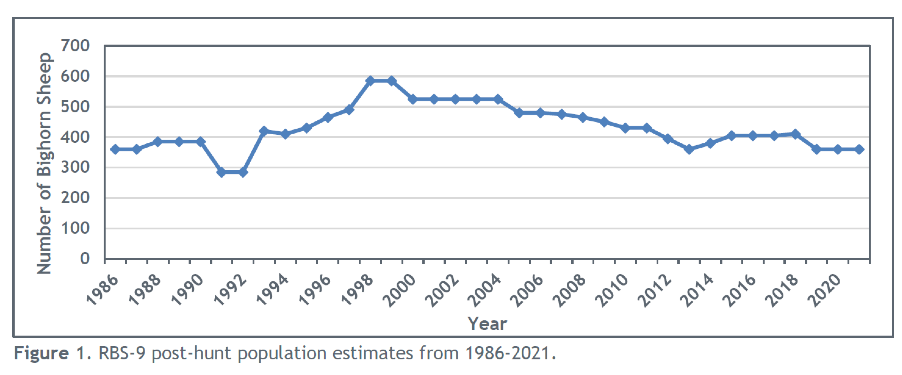

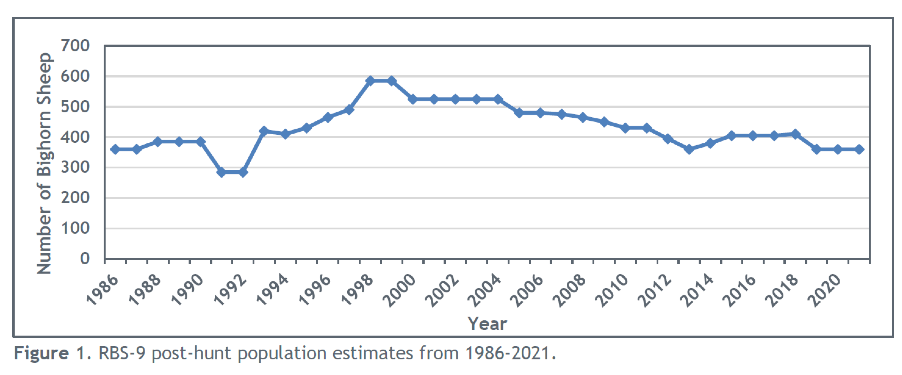

The direct conflict with the Envision information with information from CPW on this issue is direct. The CPW November 2022 Sheep management plan for the area provides the following breakdown of populations since 1986:

In discussions around the adoption of the November 2022 Sheep management plan, CPW commissioners were informed that the sheep herd is stable, at 1986 levels and the CPW managers for the area recommended no change in management for the area.[8] Candidly, the Organizations have to wonder how this situation was so poorly summarized in the Chaffee County Plan. Poor quality information such as this has significantly contributed to development of recreation plans that find no area suitable for trail expansion in the County.

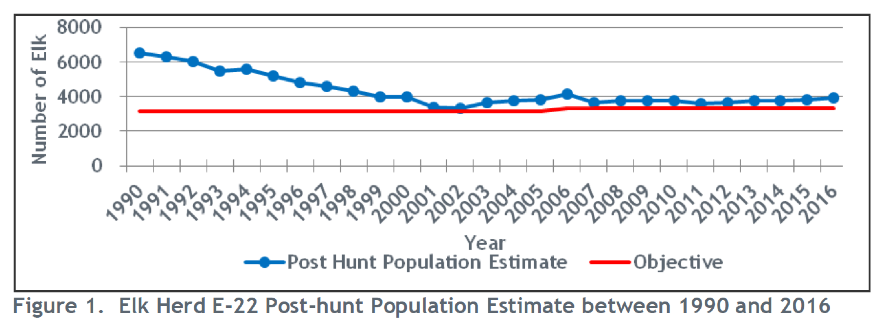

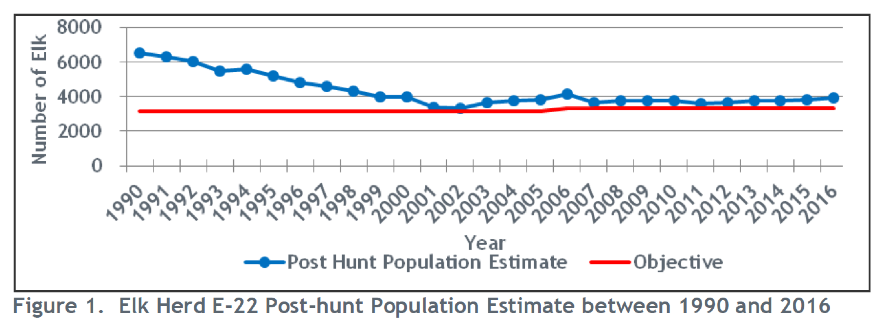

Similar conflict between the Envision Wildlife Tools for Recreation and CPW data for elk is again immediately apparent as the CPW E22 elk herd plan provides the following population history for the eastern side of Chaffee County: [9]

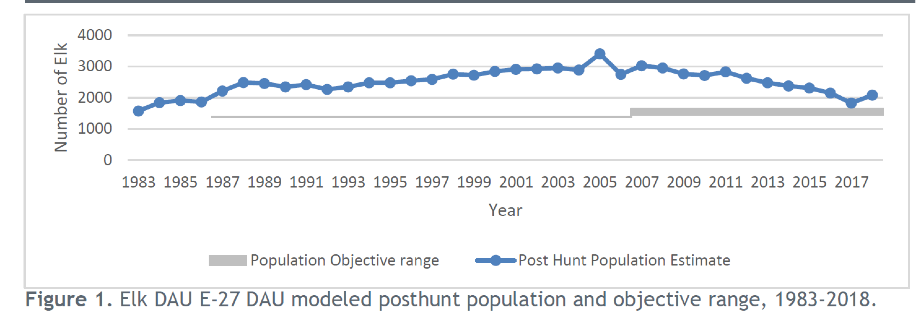

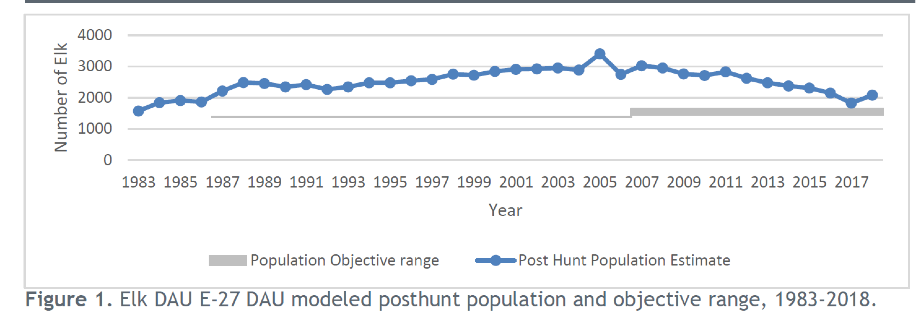

The 2020 CPW Elk management plan for unit E27 provides the following population history of elk in the western portions of Chaffee County as follows: [10]

It is interesting to note that the E27 plan provides a detailed discussion on the reason for the decline in the elk population since the late 2000’s which is:

“Harvest from 1983 to 2018 ranged from a low of 151 in 1983, to a high of 473 elk in 2016 (Figure 12). The population has been over objective since 2007 so we have increased license numbers with a resulting increase in harvest. The number of hunters per year for all seasons between 2007 and 2018 ranged from a low of 2,007 in 2008 to a high of 3,271 in 2018 (Figure 13). However, with the increase in licenses, hunter success rates have declined (Figure 14).”[11]

We are unable to locate anything resembling an 11% decline in elk populations, as the E22 population is above its 2000 population level and the E27 herd has been hunted down from its 2005 to levels present in the mid-1990s by CPW as they had concerns about game damage claims for the area. It is interesting to note that recreation is not even a priority issue in the E27 herd plan but yet we have been drawn into Envision efforts to restrict access to protect wildlife.

The Organizations believe the above references and issues provide highly credible examples of why we believe it is important to identify that populations of deer, elk and other species are reasonably good in the state currently. Even with current CPW efforts and information, too often inaccurate information is provided by many outlets and is now being found in planning documents. The Organizations are very concerned that once populations do start to decline as a result of wolf reintroductions, these issues will only get worse and require more and more effort to maintain an accurate management course regarding.

1(a)(2). Consumptive and non-consumptive recreation uses should be addressed equally, as loss of trail as a result of decline in deer and elk populations remains a primary concern.

As the Organizations have clearly stated, our concerns in this effort from day one has not centered on the direct impacts of wolves on trails users. We believe this is a comparatively easy issue that can be addressed with minimal management guidance in the Plan that trails and low speed forest service type roads do not significantly impact wolves. Rather our concerns focus on the indirect impacts of wolves on ungulates populations as trails users and other nonconsumptive users will be held responsible in misguided efforts seeking to account for ungulate population declines from wolves. For purposes of our comments, we are using the term “non-consumptive recreation” in a very general manner so as to include recreational activities that do not remove resources from the environment. This would include, but not be limited too, motorized trails users, mechanized trails users, dispersed campers, developed campers and visitors to state parks. This has already happened in the Envision effort.

While the Plan outlines, in somewhat alarming detail, the impacts of wolf reintroductions on consumptive activities such as the availability of hunting licenses, yet it remains silent on non-consumptive uses. We are not aware of concerns being raised about the safety of hunters from wolves, but there is significant concern about indirect impacts on consumptive recreation from the wolf reintroduction. We are asking for equality of protection in the Plan for all recreational interests regardless of the type of recreation they chose to pursue as our concerns are surprisingly similar. The Plan outlines the anticipated indirect impacts to consumptive recreation of the wolf reintroduction to the availability of hunting licenses for deer and elk as follows:

“Ungulate harvest objectives in Colorado may need to be adjusted over time as a result of wolves on the landscape, which will impact hunting opportunities for resident and non-resident hunters, as well as businesses that rely on hunting, such as Outfitters. Additional regulatory restrictions, such as shortened hunting seasons to reduce hunter success rates, may need to be considered in some areas where wolves become established. Management prescriptions should be based on the most up-to-date science and data available to ungulate managers.”[12]

The Organizations believe this summary of indirect impacts to the consumptive recreational activities is probably accurate and should be hugely eye opening for many in the hunting community. The Organizations are concerned that similar levels of challenges in subsequent management will be seen for nonconsumptive recreation. Seasonal closure dates for trails will get longer, more trails will be closed and usage will be displaced or lost entirely despite decades of site specific NEPA supporting use of many areas. This is an impact that must be addressed as well.

Even minimal progressions of the forecasted management situation on the ground is going to result in unprecedented conflict on almost every factor that could impact ungulate populations, regardless of consumptive or nonconsumptive classifications. Many of the public comments received at the public meetings, addressed indirect impacts and concerns, such as these, around the wolf reintroduction. The Organizations can say with absolute certainty recreational trails in the area will be drawn into these unprecedented conflicts. Everyone already blames trails for negative impacts to resources throughout the state and we have to believe that this will only get worse after wolf reintroductions. The Organizations are asking for protection or management guidance be provided for non-consumptive recreational activities be provided in the Proposal, as this type of management guidance will be valuable for our interests and partnerships moving forward. Similar guidance has already been provided for indirect impacts to consumptive recreational concerns.

The Organizations request for this type of clarity is far from unprecedented as CPW and federal partners have effectively made such statements around indirect impacts to nonconsumptive recreational issues previously in planning efforts for several species. As an example, in the most recent efforts around Wolverine listing and possible reintroductions in Colorado, CPW and federal species managers were able to provide a clear statement that there should be no change in forest management as a result of Wolverine on landscape. The previous guidance on wolverine and lynx are addressed in greater details subsequently in these comments.

The proposed listing of the Wolverine is not the only time that CPW and other land managers have addressed issues that are not a challenge in planning documents. CPW resources were heavily used in the development of the 3rd version of the Lynx Conservation Assessment and Strategy, which clearly stated trails are second level threat to the lynx and should not be a primary management concern.[13] From our perspective, this type of recognition and clear guidance of non-threats to uses is as valuable as addressing actual impacts to the species. Far too frequently in efforts around lynx management, management appears to be driven by the assertion that lynx management is needed merely because someone “saw a lynx” and managers now must do something. As a 50 or more-year partner of CPW, the motorized trail community is asking for clarity in the plan regarding the lack of impacts of trails on wolves as some protection for our nonconsumptive interests. This has not been provided.

1(a)(3) Wolves will cause ungulate population declines as ungulates are counted without regard to age or infirmity.

While the Organizations welcome the clarity that has been provided around the existing ungulate populations in the Proposal, the Proposal falls well short of addressing all our concerns. A huge portion of the research we have been able to locate focuses on wildlife impacts from wolves on the basis that predominately old or sick animals are eaten by wolves. While this topic may be an interesting academic discussion, it is proof that populations will not increase for deer and elk or probably even remain the same. This whole discussion is centered around a decline in population of these species as a result of the wolf presence, and it is this decline in populations that is most concerning to us. We have reviewed many herd management plans throughout the State and have never seen any management summary even attempting to identify old or infirm animals or take the position that these animals would have died anyway. While the fact that wolves predominately eat old or sick animals may be true, it will be useless in subsequent planning efforts as no one will be able to count how many animals were sick or old when they were eaten. We must question if information like this could even be developed making this discussion largely useless in resolving our concerns.

1(a)(4). Management guidance should reflect the broad scope of concerns from the wolf reintroduction.

The Organizations are also concerned that the current focus on consumption recreation while largely overlooking nonconsumptive recreation in the Plan fails to address how the wolf reintroduction is being funded. House Bill 21-1040 clearly changed the funding model for the wolf reintroduction from one borne by those that chose to support CPW to a model where wolf management is funded by everyone that was involved in the wolf reintroduction. Addressing a wider range of issues in the Plan beyond merely consumptive concerns would be a cost-effective manner to show that CPW has been responsive to more than their traditional funding base. The Organizations submit that there is significant value in this message alone as we are sure that the discussions around wolves and funding is FAR from over at this point.

1(b)(1). There is a need for strong and clear statements on gray wolf management issues as a result of the national uncertainty around the species.

The high level of uncertainty around the national management situation for the gray wolf means detailed, strong statements of positions and information at the state level are more critical now than ever before. The Organizations would ask for clarity in the Plan around issues where there are NOT management concerns, as well as on issues where there are problems. It has been our experience that while there is a high degree of certainty around the lack of management concerns to nonconsumptive activities when landscape level plans are developed, this certainty will erode or be silenced when management challenges are subsequently addressed in site specific planning. This situation can only be remedied with strong and clear management statements in the Plan on all issues, which are made more valuable as a result of the national uncertainty around wolf management.

Wolf management is another highly contentious national issue with almost 50 years of listings, litigation and Congressional action involved in the discussion. There are abnormally high degrees of uncertainty around wolf management that result from the relisting of gray wolf nationally as a protected species for ESA purposes and notice of intent to sue on lack of 5-year assessment for wolf. We are also intimately aware of the impacts that the lack of clarity nationally has had on wolf management in adjacent states. The decades on conflict and uncertainty in adjacent states are something the nonconsumptive recreational community would like to avoid at all costs.

The Organizations are asking for clear and direct statements regarding possible conflicts and issues where there are not conflicts from reintroduction is the fact that some groups have taken positions that are simply at odds with anything that they have done before. As an example, Wild Earth Guardians has now taken the position that there are too many deer and elk in Colorado and that the population should be reduced. This is a significant departure from everything we have ever heard from this group in any planning effort and this is concerning for many reasons. Do we expect this unusual course of action to return to any variation of normal in the near future? No. We expect groups to continue to push their desires around wolves in every manner possible and this will cause credible general information on issues that are settled to be more valuable than ever before. It is unreasonable to expect nonconsumptive users to reinvent the wheel on an issue every time the discussion heads an unexpected manner. We believe developing the Wolf Plan to address as many possible issues, even generally, will mitigate this type of conflict.

1(b)(2) Environmental factors impacting wolves and ungulate species responses to reintroduced predators are not particularly well understood nor are they consistent across species.

Equal treatment of consumptive and nonconsumptive recreational activities in the Plan is needed as a result of the limited understanding and uncertainty we are seeing around natural activities of wolves and the response of ungulates to reintroduced wolves at the local level. As an example of the limited understanding of wolves currently possessed, factors such as high snowfall have recently impacted wolf behavior and populations in Canada.[14] Similar unusual behavior of ungulates has already been noted in Northwestern Colorado as a result of the unprecedented snowfalls limiting access of ungulates to food. Antelope in this area are being forced onto roadways and are now being struck in large numbers, which is a highly unusual occurrence. Could the presence of wolves in an ecosystem already stressed due to unusually high snowfall compound the issues we are seeing to an exponential level? That answer is possibly and that relationship is not well understood. Could wolves on the landscape cause deer to be struck on roads in a larger number on deep snowfall seasons? Possibly. Seasonal fluctuations such as this can be addressed but that type of management response is not facilitated if efforts become misdirected due to a lack of information or understanding of the issue. We don’t want to have to fight for trails while researchers are resolving this question. Based on our previous experiences that could take decades.

Even without environmental pressures, such as unusual snowfall, these clear general statements of management guidance will be necessary to address the uncertainty in forecasting the response of ungulates to the presence of an alpha predator in the ecosystem. Research indicates that there is the high level of uncertainty in forecasting this type of response around any predator reintroduction efforts and often that different species respond differently to the same predator. Researchers in Canada have explicitly recognized the varying responses of ungulates around the reintroduction of cougars into a park area as follows:

“The presence of cougars during the past decade apparently caused deer and elk to leave the security of forest cover that now harbors a highly effective predator (Figure 3). Mule deer responded most strongly to the presence of cougars, increasing 6% per year outside the Park relative to inside even though total counts decreased throughout the study period (β = – 0.037, P = 0.03), and specifically showing a 7% rise in their occurrence on grasslands and agricultural land cover types relative to forests (β = 0.133, P = 0.001)…. When new predators establish and their population explodes within a decade, as has been the case for cougars in the Cypress Hills, we expect to see direct effects on prey population size resulting from predation; indeed, 76% of cougar kills in the Cypress Hills were deer, and 15% were elk (Bacon et al. 2011). Anticipating and planning for the indirect effects of a landscape of fear is more difficult”[15]

The poorly understood nature of the ungulate response to fear from a reintroduced alpha predator was recently outlined in great detail by other researchers who concluded as follows:

“Similarly, in systems where predators have been locally extirpated and are later reintroduced or naturally recolonize, wild prey animals may be naive to risk cues. This naivety has been observed in multiple ungulate species in response to wolf extirpation and recolonization in North America and Europe, and while some populations quickly learn to fear predators, others have not exhibited typical anti-predator responses even after generations (Berger, Swenson, & Persson, 2001; Sand et al., 2006; Berger, 2007b). Further species-specific research is needed to understand the consequences of predator reintroduction for prey behavior and demography and inform potential management strategies.”[16]

Yet more researchers have summarized the poorly understood nature of the fear response of ungulates to newly introduced predators and how this is a management concern as follows:

“In the presence of predators, prey generally alter their behavior to become more difficult to capture, detect, or encounter. Antipredator behaviors are a complex suite of innate and learned behavioral responses, which can be individual or species-specific (Chamaillé-Jammes et al., 2014; Thurfjell et al., 2017). They can be affected by predator species and habitat characteristics.” [17]

This research goes into a huge number of factors that must be understood more completely to allow these unintended and poorly understood impacts to be locally managed. These researchers outline even more management tools that could be applied to address ungulate response to predators, once these unintended responses are understood better. Large portions of the possible management do not involve the management of a human presence in the eco-system. While this is an interesting discussion and could be management that could be facilitated around the Colorado wolf reintroduction, again the nonconsumptive recreation community should not be asked to wait for the conclusions of this research in order to maintain recreational access.

Clearly, research indicates that wildlife is going to respond to the presence of the new predator in an ecosystem, that species don’t respond the same and we really don’t understand exactly what that response will be. Despite it now being almost a decade after research was conducted around the ungulate response to the cougars in the Canadian Park, we are unable to find any research indicating when deer and elk returned to the Canadian Park or if they returned at all. While the wolf reintroduction may facilitate ground breaking research and resolve this scientific uncertainty identified above, the Trails community should not have to fight for trails when all the wildlife disappears from portions of the state as a result of the wolves being present and then hope research is completed to allow us to reopen trails. This type of research could easily span decades to resolve and create exactly the impact and challenge that the Plan is supposed to be resolving. People will be mad when the deer and elk locally disappear and that will not be related to nonconsumptive recreational impacts. These interests are entitled to protection under the Plan and that protection has not been provided.

If we return to the Northwestern Colorado snowfall situation, management guidance could greatly assist in this situation by simply eliminating factors that simply don’t make sense. Could managers look at feeding away from roads? Maybe. Could this draw predators to the feeding area? Probably. Should managers educate users of the road to slow down as large numbers of animals could be on the road? Yes, as this is a safety issue for the animals and motorists. Should managers be closing recreational access in the backcountry when populations decline? Probably not, as this will create conflict and may actually impair management actions such as plowing of grazing areas or feeding efforts and impair researcher access to these areas. Decades of research into this issue have been unable to substantiate any significant relationship of recreational access in the relationship of introduced predators on other predators and ungulate species and nonconsumptive recreational users should not be held accountable for this situation.

1(c)(1). Idaho wolf planners have proactively addressed the indirect impacts of wolves on other predatory species in their wolf planning efforts.

The Organizations have been directly involved in many efforts trying to understand the indirect relationship a single predator may have on other predators in the area and how environmental factors may provide an indirect comparative advantage to one species or the other in the ecosystem. Many of these efforts have started with partners and in other states decades ago. Trying to understand the indirect relationship between predators is another example of the highly theoretical research that seems to plague predator management as it has been our experience that these concerns simply can never be resolved. These types of theoretical concerns have consistently resulted in lost recreational access due to decision making from highly cautious land managers seeking to avoid possible impacts to other predators from the presence of wolves. When efforts such as this started in Idaho, Idaho provided guidance to mitigate possible impacts from the issues being researched, which did help mitigate impacts. It should be noted that the motorized community has lost access even with these protections being in place. As a result, we are asking for stronger protections in Colorado around the wolf reintroduction.

The possible indirect impacts of predators on other predators and ungulate species have resulted in many challenges for nonconsumptive recreation including concerns around winter grooming and possible snow compaction from winter usage. This snow compaction concern started as a highly theoretical concern many decades ago but subsequent research has been unable to resolve this concern despite decades of research. Sometimes concerns center on increased competition between predators, such as lynx and coyotes due to snow compaction while other concerns have centered on predators being able to travel further faster and impacts ungulate populations such as caribou that can result. No matter how much research was conducted, there was always a different twist on the challenge that had to be researched more. With wolves, we are seeing concerns that summer roads and trails are creating similar types of concerns and that question concerns us greatly. Protections, such as those we are seeking could facilitate further partnerships with researchers such as those we have participated in already. We would be hugely concerned about research such as this without clear management protections in place.

As mentioned elsewhere in these comments, these types of abstract concerns can be litigated decades after reintroductions have been declared a success and CPW has moved on. This concern is exemplified by the 2022 litigation challenging the Rio Grande NF resource management plan, where the following allegations around lynx behavior were made in the Complaint:

“Snow compaction can crush subnivean spaces and alter the competitive advantage that some snow-dependent wildlife, such as Canada lynx, enjoy over coyotes and other predators.”

Introducing wolves into highly abstract management similar to those exemplified above will not bring clarity or access to lands in planning but will further cloud the already abstract questions of existing species relationships. This is a serious impact for our interests and must be addressed in the Plan. The Organizations would like to avoid litigating the relationship between wolves and lynx to protect recreational access more than 20 years after the wolf reintroduction has been completed and declared a success. We are asking for as much clarity as can be provided in the Plan as possible on this issue as the Plan is entirely silent on this issue.

After a preliminary review of wolf specific research, similar theoretical concerns about the predator/predator relationship appear to exist around wolves as continue to be challenges with the lynx. Concerns about wolves impacting other predator populations, such as the lynx, continue to exist, even if there is no supporting research whatsoever.[18] Nationally recognized lynx experts have firmly resolved this theoretical concern in the negative but the issue remains present. [19] Idaho wolf management documents recognized this issue and have specifically addressed the predator-to-predator type of impacts in their wolf planning documents as follows: [20]

“Wolves presumably interact in various ways with other predators and other species of concern. Wolves compete indirectly with other predators by preying on the same prey species, but have also been documented to kill mountain lions (Boyd and Neale 1992; Boyd et al. 1994; T. Ruth, Hornocker Institute, in prep.). Likewise, wolves have been documented to kill coyotes (Boyd et al. 1994, Crabtree and Sheldon 1999) and researchers occasionally report observing wolves harassing bears in attempt to chase them off ungulate carcasses. It is likely that other large predators also occasionally usurp kills from wolves. Lions visited or scavenged about 3% of wolf kills while wolves visited or scavenged 20% of mountain lion kills (Kunkel et al. 1999). However, little is known about the frequency and effects of these interactions among wolves and other predators, other endangered or threatened species, or species that are candidates for listing as endangered or threatened. The Department will attempt to investigate these relationships to the extent possible as the wolf population increases.”

The State of Idaho recognized the possible impacts of this inconclusive research and has chosen to directly address these types of predator/predator secondary impacts in their planning documents around the wolf. This protection facilitated the motorized community participation in subsequent research efforts on the issue as a partner rather than an outside interest that opposed the research. We have been consistently told this partnership was important to subsequent research efforts. We would ask that issues such as this be addressed in the Colorado plan with at least the specificity that it has been addressed already in Idaho. As noted in other portions of these comments, the motorized community again had to defend another legal challenge to lynx management as existing management document were not providing sufficient protections and management clarity to lynx.

Over the 20 years following Idaho efforts, the motorized community has worked outside just defending litigation around the predator/predator relationship and the possible impacts to this relationship from recreation. As a result of the protections Idaho has provided around the wolf, we have partnered with researchers in an attempt to resolve this cross-species type of uncertainty for environmental conditions. CSA has partnered with the Idaho Snowmobile Association in supporting the work of nationally recognized experts, US Forest Service Research Stations and the US Fish and Wildlife Service exploring the relationship of recreation of the wolverine and its possible facilitation of negative impacts on other predators. These efforts were significant enough that Idaho Snowmobile Association was recognized as a partner on this study.[21]

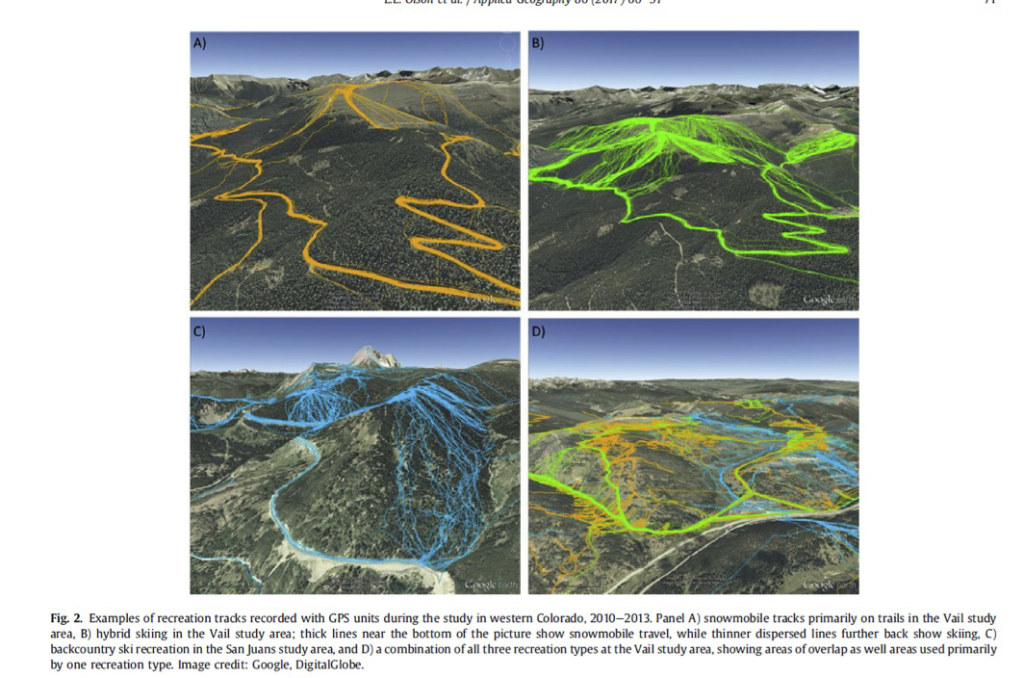

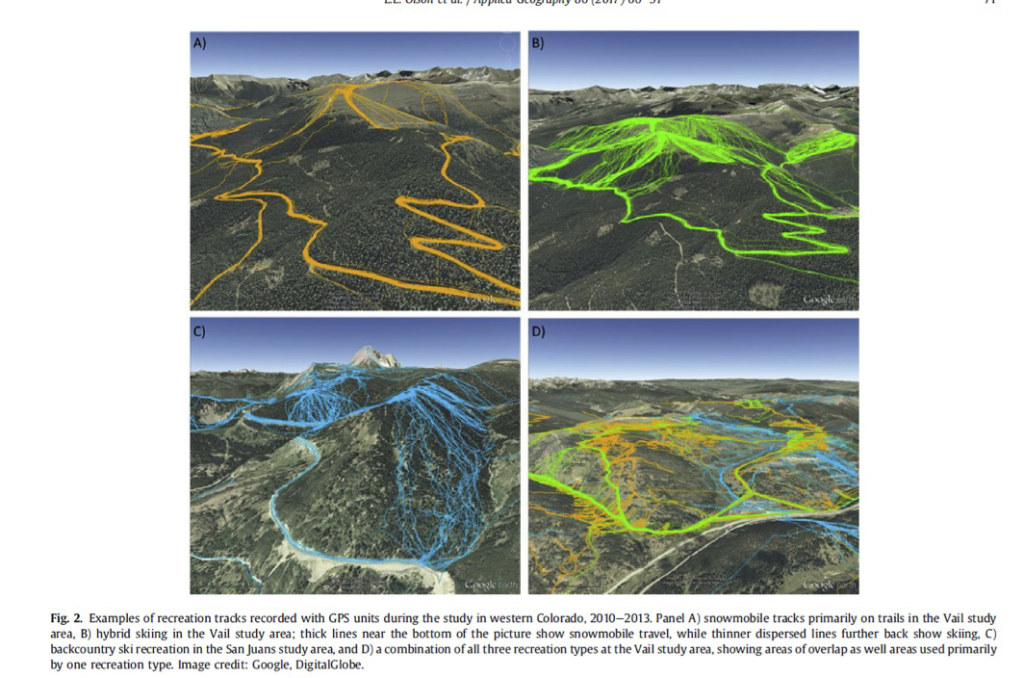

These predator/predator/recreation study efforts were continued by lynx managers in Colorado to understand snow compaction and the relationship of lynx to recreational users with the support of Colorado Snowmobile Association in partnership with CPW. CSA partnered with researchers in a variety of ways from building confidence in the snowmobile community to even participate in the study on Vail Pass, to supplying fuel and oil for researchers to recovering large amounts of stuck equipment in the backcountry and teaching researchers how to ride safely in the backcountry. This research developed information about the real time response from predators to recreational usage as follows: [22]

Even with nationally recognized cutting-edge research such as this, the Organizations still are litigating this relationship and this type of question remains a problem for almost any planning effort. It has been our experience that despite everyone’s best efforts, uncertainty such as this simply never go away. That is a situation we would like to avoid moving forward involving yet another species, as we assert there needs to be some type of process to recognize there is not a strong relationship of these types of factors. Without basic protections such as this there is no way the motorized community would ever participate in or support research on issues like this. We would simply have too much at risk.

While our Organizations have not had to deal directly with these issues around wolves, the reintroduction of wolves will bring yet another species into this predator/predator/prey discussion in Colorado. The relationship of wolves and roads and trails seems to be an equally messy discussion as we have had to address with other species. Some research finds a benefit to wolves from roads,[23] other research indicates roads are safer with wolves being present and benefits to the wolves,[24] while other research indicates a weak negative relationship between roads and wolves.[25] Other research appears to indicate there is a negative impact on ungulates from wolf predation as the wolves can move longer distances faster.[26] The Organizations can state with absolutely certainty that we have lost access to trails as a result of this type of uncertainty with other species and these are exactly the issues we believe the Plan must be addressing to satisfy the requirements of Prop 114. Given that more than 20 years of research, partially with CPW, has established the lack of relationship of any size on this issue, the Organizations request this conclusion be clearly stated in the Plan. Idaho has already provided protections such as this and it has been a “win” type situation for everyone. As noted in other portions of these comments, Wisconsin has clearly recognized the lack of relationship between dispersed nonconsumptive recreation and wolves and is seeking to protect the benefits of recreational access to wolf habitat as an economic driver.

1(c)(2). Wisconsin has proactively addressed nonconsumptive trail and access issues in their updated Wolf planning documents.

The Organizations would be remiss if we did not recognize the direction that the State of Wisconsin has taken in addressing recreational access around wolf management in our comments, as Wisconsin efforts are occurring at almost the same time as Colorado efforts. Wisconsin has recognized the value of nonconsumptive recreational access to wolves and is seeking to more fully understand and develop this economic resource for local communities. This effort is highly relevant as the revision to the Wisconsin Wolf Plan is occurring at almost exactly the same time as Colorado is developing their Wolf plan under Prop. 114. While we have some concerns that this direction of management might create its own challenges, such as safety of wildlife watchers, the positive correlation of access, wolves and revenues warrants discussion and analysis in the Colorado Plan.

In the November 9, 2022 version of the updated Wisconsin wolf plan,[27] the Wisconsin Dept of Natural Resources proposed the following goal of the Wisconsin Plan:

“Product E2b: Develop a recreational behavior and economic analysis to explore the ways that wolves influence the attitudes and behaviors of various recreational user groups, including deer and grouse hunters. Currently, wolf distribution covers over a third of the state, including vast areas of public lands which simultaneously support many forms of recreation, tourism and sources of economic stimuli. It is therefore important to better understand the net effects of

wolf presence across the state on recreational users. For example, many dog owners may choose to recreate (hunt, hike, etc.) in areas away from wolves to avoid conflict and this may result in a net opportunity loss for those users and redirection of spending. Others may quit hunting or recreating with their dogs entirely due to fear of losing a dog to wolves. Still other users, such as winter recreationists, campers, or hikers, may be indifferent to or even selecting for areas with wolf presence. Finally, those driven to see or observe wolves (ecotourism) are likely to be drawn to areas with wolves. An improved understanding of this dynamic would help improve holistic recreational planning, identify educational and outreach needs, support hunter recruitment and retention efforts, and provide information to help support local economies.

Product E2c: Evaluate the potential impacts of wolves and wolf presence on recreational land values. Department staff routinely hear from some members of the public during individual interactions and at various meetings (such as County Deer Advisory Council and Conservation Congress meetings) that the presence of wolves and the implied reduction in hunting opportunities have reduced recreational land values and created economic loss and hardship to these landowners. The plan recommends this dynamic be explored further to determine the extent to which this may or may not be occurring.”[28]

The Organizations would note that the basic issues and direction for this nonconsumptive type discussion of these goals is not addressed in the Colorado Plan in any manner. Obviously protecting access to these areas is a cornerstone of this type of economic development effort. While the Organizations are not proposing detailed research or other research on this issue, we do believe that maintaining access for this type of nonconsumptive ecotourism effort is warranted and should be provided for in the Colorado Plan as well. It would be unfortunate to be in the situation where Wisconsin’s research has identified a major economic driver and revenue stream for the agency, but Colorado is unable to leverage this resource due to the loss of access to public lands as a direct and indirect result of the reintroduction of the wolf. Candidly, Colorado should strive to at least keep up with other states on issues such as this.

1(c)(3). While other states have embraced collaboration and clarity in management to avoid impacts, the Colorado Plan appears to assume only closures work.

The Organizations are concerned with many aspects of the Plan which are internally inconsistent or conflicts with general CPW authority. The Organizations are hugely frustrated with the portions of the Plan that assert land closures will be necessary to protect wolves. The Organizations are simply offended at the cavalier manner that closures are recognized as the ONLY tool for wolf protection by the Plan, despite so many other states recognizing the value of nonconsumptive access and protecting it in new ways for the benefit of the wolf. This is in direct conflict with pretty much every collaborative we have done with CPW for decades and totally conflicts with numerous provisions of the Plan where CPW asserts it lacks authority to make decisions on lands not owned by CPW.

The Organizations are vigorously opposed to any assertions in the Plan that any closure of lands may be necessary for the protection of wolves. This is at best entirely pre-decisional for any subsequent local planning efforts. The Plan assumes that closures will be necessary for the management of wolves as follows:

“Therefore, it will be important for federal agencies and CPW to collaborate on land use issues as they relate to wolf management, which may include recreation, grazing management, public access, or habitat manipulation. CPW will facilitate on-going collaboration with Federal land managers in instances where wolf presence or behavior may warrant temporary public land access restrictions.”[29]

The Organizations are unable to understand how this type of a provision could be found in the Plan at all as it asserts that closures will be needed on public lands to address wolves, and we know from decades of experience that closures create conflict and generally don’t solve problems. Management tools, with proven track records of success in balancing wildlife and recreation like seasonal closures or educational resources for wolves are simply not even mentioned in the Plan but closures are. This sends a strong and negative message to the trails community.

Not only is there no discussion of how this broad closure authority was thought to be worthy of inclusion in the Plan, there is no attempt to reconcile this provision with other sections of the Plan that specifically assert CPW does not have this authority. There is also no attempt made to provide a scientific basis for the need for closure authority or steps that must be taken prior to closures to mitigate impacts of even a single closure. CPW has outlined the value of incremental management use of all forms of management tools before closures for 61 pages in the 2021 Trails and Wildlife Guide.[30] We must ask why that decision making model would not be fully applicable here? This Guide is not even mentioned as a management resource in the Plan at all, which is disappointing as the Guide was designed to be a species neutral guide for all forms on nonconsumptive recreation that was adopted by CPW and all federal managers.

The lack of clarity in this provision is astonishing as well as we are unable to understand what uses might be subject to closures and what might not? How long would a closure be in place? Is temporary a day or years. How are closure boundaries set? Who enforces closure boundaries? Who does the closure boundary apply to? Everyone? Just motorized? How would a closure impact hunting? How would a closure impact grazing in the area? Are these damages that could be recovered by the victim of the closure? As more than 50-year partners with CPW we at least deserve a discussion of these questions, and that has not been given at all. It is frustrating that silence from CPW has been provided despite so many opportunities to defend nonconsumptive recreational interests. It is infuriating to see that closures are seen as the only tool for management by interests within CPW despite this 50-year partnership and massive internal resources being created in partnership with CPW.

1(d). Management guidance for dispersed nonconsumptive recreation in the Plan falls well short of guidance provided on similar species in the past by CPW.

The Organizations are also disappointed that the management guidance in the Plan falls well short of the management clarity that has been provided for similar species, like the Wolverine reintroductions addressed 10 years ago by CPW. While similar protections have been provided in many other species management efforts and listings, comparisons between wolves and wolverine management situations is highly relevant. As we have attempted to outline in these comments often research on these issues crosses specific species designations and may impact many other species. Generally, both are highly mobile habitat generalists and can survive in a wide range of situations and both species have along and twisting relationship with the Endangered Species Act generally. Protections in wolf planning efforts for recreation provided in Idaho have facilitated research for the benefit of wolverine possibly being reintroduced in Colorado.

Comparisons of the wolverine and wolf are also highly relevant as management documents for each have followed similar paths of development. Wolverine discussions between USFWS, CPW and interested organizations, such as motorized trails, the farming and ranching community, the ski industry and others spanned more than a year. These efforts centered around the use of rules such as 10J and 4d to provide protection for the wolverine along with protection of participant interests in the process.

Similar legal processes to the wolverine effort are being applied for the wolf reintroduction as well. The alignment of these wolverine meetings and the SAG and TAG efforts that CPW has undertaken for the wolf is significant as well. Our records indicate that 5 CDOW representatives consistently attended all wolverine collaborative meetings. This course of conduct clearly indicates input of CPW has always been valued in reintroduction discussions and that CPW input has always been heavily weighted in the management of all lands in the state. No rational argument that can be made that DOW could allocate this level of time and resources to an effort they expected to get nothing out of. This effort was always a two-way street.

While the two species and two processes used for facilitation are highly similar, the differences in the treatment of dispersed nonconsumptive recreation could not be more stark. As a result of the collaborative efforts on the wolverine, dispersed recreation was clearly identified as a low-level threat to the wolverine planning documents as follows:[31]

“Under the proposed NEP designation, any effects from skiing activities to wolverine would not be prohibited by the ESA. These activities either do not significantly affect wolverines (dispersed recreation) or occur at a small scale relative to wolverine habitat (developed ski areas, snowmobile play areas) such that the overall effects of these activities are not significant to wolverine conservation. Wolverine populations persist and have expanded in the presence of these activities and the available scientific information does not indicate that they pose a threat the DPS…. The Service also believes that the benefits of providing assurances that their activities are protected to residents of the affected states outweigh the costs in terms of a small conservation risk to wolverines.”

By comparison we are unable to find any guidance or other resources in the Plan that provides for this type of guidance on nonconsumptive recreational concerns despite the similarities of the species and planning efforts. This simply must be corrected as the wolf reintroduction should be building on the success of previous collaboratives not regressing from them. We believe that impacts of both of these efforts will be highly similar and we are aware of several instances where this guidance has avoided impacts to nonconsumptive recreation in areas where there may have been a wolverine seen at one time.

1(e). Litigation of wolf issues will continue for decades after the CPW wolf plan is completed.

The Organizations are intimately familiar with the fact that while species specific landscape level planning documents are completed within a few years, court litigation over the application of these documents can continue for literally decades. What is more important to understand is the fact that this litigation may not even directly involve CPW or other interests but may be involving challenges to forest plans and other site specific NEPA efforts. CPW is rarely a party to any of these actions but this does not mitigate the fact that these are significant impacts to the parties involved and should be mitigated in the Plan.

An example of the litigation of indirect impacts from ambiguities in traditional species planning documents has recently occurring as a result of the Rio Grande NF revision of its forest plan. The Forest has been sued twice over lynx management issues, despite lynx being on the ground for more than 20 years and CPW declaring the reintroduction a success more than a decade ago. One of these suits directly addressed motorized usage on the Rio Grande National Forest despite the fact that this had been clearly addressed in the 2013 LCAS with reasonable clarity. The second involved the sufficiency of the §7 consultation of the USFWS on the Rio Grande Forest Plan on the issue of dispersed recreation and changing ecosystems. Our Organizations were forced to intervene in defense of one of these matters, as the litigation sought remedies that would have enjoined many forms of recreation on the forest while the matter was resolved in the Courts. While one lawsuit was dismissed,[32] the other matter we have intervened in remains only partially settled and ongoing.[33] These are impacts and conflicts in every sense of the term and ones that we are all too familiar with addressing. We think introduction of the wolf into these types of legal discussions without management clarity will only compound problems and challenges like this. As a result, we are asking for protections under the Plan.

While the Organizations are aware that no planning document can prevent litigation, the Organizations are aware that planning documents can heavily impact the speed of resolution of these matters and the scope of the remedy that is sought in the litigation. It is unfortunate that the Organizations believe this type of litigation could easily continue for the wolf decades after the CPW plan is completed. The Organizations are asking for as much clarity as possible about the lack of impact of low-speed roads and trails on wolves and the possible impact of wolves on other species as possible to allow matters such as this to be resolved as quickly and effectively as possible. These are impacts and conflicts that warrant mitigation measures in the Plan to the fullest extent possible.

2(a)(1). CPW must address species on federal public lands and recreational opportunities pursuant to its enabling legislation.

CPW has a broad mission to manage wildlife and recreational opportunities in the State pursuant to its enabling legislation. The Organizations helped create this legislation as part of the merger of CPW. Despite this broad authority, CPW takes the unusual position of asserting there are limitations on this management authority over wildlife. Often these limitations are asserted to be based on interpretations of CPW statutory authority that cannot be supported when reviewed further. These internal conflicts in foundational issues, such as CPW ability to guide and direct management on federal lands must be addressed consistently and broadly in the Plan to avoid confusion and conflict moving forward. The failure of CPW to address wildlife on federal lands only compounds the impacts from the absolute silence on nonconsumptive recreational issues that are statutorily required to be developed under this general authority as well. While we are aware there is a lot of pressure on CPW for many reasons right now, avoiding this discussion will only create more conflict in the future.

As an example of this type of internal conflict between standards and the enabling legislation, the Plan attempts to avoid providing guidance on uses on public lands as follows:

“.. Federal land management agencies have sole management discretion over their lands. CPW has no legal authority to implement restrictions or land management prescriptions on lands it does not own or lease. Therefore, it will be important for federal agencies and CPW to collaborate on land use issues as they relate to wolf management, which may include recreation, grazing management, public access, or habitat manipulation. CPW will facilitate on-going collaboration with Federal land managers in instances where wolf presence or behavior may warrant temporary public land access restrictions.”[34]

The Organizations were surprised at this assertion of authority, as it is a significant change in the management direction from CPW efforts historically. While there may be federal regulations around the experimental nonessential designation for wolves on federal lands, this does not absolve CPW of their statutory obligation. Alignment of CPW and federal managers on issues like this sends an important message.

The silence of this provision on nonconsumptive recreational concerns is noted as well, as this type of authority is again provided by the CPW enabling legislation. We are not asserting that CPW has direct management authority over lands under federal management, but CPW has primary management authority over most of the species that reside on those lands. Even those species where management may be shared by US Fish and Wildlife Service, the shared nature of CPW authority has never been contested. Often CPW is a primary source of information and researchers for the management of species on the ground as USFWS lacks these types of resources. CPW has broad authority over species management issues and that authority directly applies to all lands in the State. CPW routinely provides hugely detailed comments on a wide range of projects and efforts on federal public lands. If there was no authority for this type of management, we must question why such actions would be undertaken?

CPW’s general authority to perpetuate wildlife resources of the State is clearly stated on the CPW website “the agency manages All of Colorado’s Wildlife…. And works to protect and recover threatened and endangered species”. [35] CPW’s statutory authority explicitly provides an even more wide-ranging grant of authority for the management of wildlife in the State to CPW as follows:

“(1) It is the policy of the state of Colorado that the wildlife and their environment are to be protected, preserved, enhanced, and managed for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the people of this state and its visitors. It is further declared to be the policy of this state that there shall be provided a comprehensive program designed to offer the greatest possible variety of wildlife-related recreational opportunity to the people of this state and its visitors and that, to carry out such program and policy, there shall be a continuous operation of planning, acquisition, and development of wildlife habitats and facilities for wildlife-related opportunities.

(2) All wildlife within this state not lawfully acquired and held by private ownership is declared to be the property of this state. Right, title, interest, acquisition, transfer, sale, importation, exportation, release, donation, or possession of wildlife is permitted only as provided in articles 1 to 6 of this title or in any rule of the parks and wildlife commission.”[36]

The immediate conflict of the Plan provisions with CPW general enabling legislation is evidenced when the authority of the CPW commission is reviewed. This authority is specifically provided as follows:

“(1) The commission is responsible for all wildlife management, for licensing requirements, and for the promulgation of rules, regulations, and orders concerning wildlife programs.

2) The commission shall establish objectives within the state policy, as set forth in section 33-1-101, which will enable the division to develop, manage, and maintain sound programs of hunting, fishing, trapping, and other wildlife-related outdoor recreational activities. Such objectives shall employ a multiple-use concept of management….

(5) The commission may coordinate with the United States secretary of the interior and the United States secretary of agriculture to develop wildlife conservation and management plans consistent with this title for federal lands pursuant to 16 U.S.C. sec. 530, 16 U.S.C. sec. 1604, and 43 U.S.C. sec. 1712.”[37]

CPW enabling legislation also provides broad general powers to the agency to address recreational issues throughout the State as follows:

“(1) It is the policy of the state of Colorado that the natural, scenic, scientific, and outdoor recreation areas of this state are to be protected, preserved, enhanced, and managed for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the people of this state and visitors of this state. It is further declared to be the policy of this state that there shall be provided a comprehensive program of outdoor recreation in order to offer the greatest possible variety of outdoor recreational opportunities to the people of this state and its visitors and that to carry out such program and policy there shall be a continuous operation of acquisition, development, and management of outdoor recreation lands, waters, and facilities.”[38]

While the subsequent provisions of the above section provide examples of recreational management issues, the Organizations are unable to find any application of these examples in a manner that diminishes other broad grants of authority in these provisions.

The Organizations are unable to find any portion of Prop 114 that reduces or diminishes the broad general grant of authority to CPW with regard to species on lands throughout the State or the requirement to address all forms of recreational opportunities. Any assertion that CPW does not have broad general authority over wildlife management and recreation is highly frustrating to the Organizations, as our representatives were heavily involved in crafting the above legislative language as part of the merger of DOW and Colorado Parks. We can say with absolute authority that the scope of wildlife management authority was some of the most lengthy and contentious portions of the merger effort and if the current interpretation of this authority was moved forward the legacy of Colorado Parks would simply cease to exist.

Not only does CPW have a broad grant of statutory authority for wildlife issues, CPW has always vigorously participated in management of all lands in the state for wildlife issues. Exhaustive OHV grant specific comments have been provided by CPW on all projects throughout the State despite the fact the overwhelming portion of these occur on federal lands. CPW has ALWAYS addressed management of federal public lands in herd plans. CPW has always provided wildlife comments on any federal planning effort. On some planning proposals, these CPW concerns have spanned hundreds of pages outlining concerns and possible impacts. While these comments are FAR too long to summarize here, CPW recently asserted jurisdiction over wildlife on federal lands on the Pike/San Isabel National Forests as follows:

“Impacts to Wildlife from Recreation: Outdoor recreation associated with roads and trails can negatively impact wildlife species at the individual, population and community levels through direct and indirect mechanisms. Direct disturbance results from the physical loss and fragmentation of habitat from road, trails, and any associated infrastructure.”[39]

The Organizations are simply unable to understand any assertion of limited wildlife authority on federal lands are allowed in the Plan. This is simply incorrect. The Organizations are even more troubled by the fact the Plan is utterly silent on nonconsumptive recreational concerns around the wolf as recreation is 50% of the agency mission. There is not even an attempt to address this portion of the enabling legislation authority or continue CPW engagement with these issues as has been the baseline of understanding for decades. This is really frustrating to the Organizations as creating this balance of interests was the basis of years of effort from our representatives at the time of the merger of CDOW and Colorado Parks. This per se legal deficiency must be addressed.

2(a)(2). CPW has successfully litigated to defend their authority over species throughout the State.

This narrow scope of CPW jurisdiction outlined in the Plan is not supported by recent settlements of legal proceedings brought by CPW where broad wildlife management authority across the State was defended and recognized by federal managers. An example of CPW litigating to defend this broad scope of authority would be provided by the fact that CPW recently sued the BLM over concerns for possible wildlife impacts in the Uncompahgre Field Office.[40] In the 2022 settlement agreement for this litigation, BLM recognized the authority of CPW to manage big game and other species and other important habitat areas as follows:

“The Parties agree that BLM will complete a statewide Resource Management Plan Amendment (“RMPA”) addressing, at a minimum, the management of oil and gas and associated infrastructure in big-game migration corridors and other important big game habitat areas on BLM-administered lands in Colorado.”

As a result of this litigation, BLM moved forward with planning for wildlife corridors on BLM lands across the State. In the scoping for this massive planning effort, BLM made the following recognition of the authority of CPW to manage species:

“The BLM recognizes state authority to conserve and manage big-game species. In 2019, the Governor of Colorado, Jared Polis, signed Executive Order D 2019 011, Conserving Colorado’s Big Game Winter Range and Migration Corridors. In 2020, the Colorado Parks and Wildlife updated their action plan for Implementation of Secretarial Order 3362. In 2021, Colorado Department of Natural Resources released a report titled Opportunities to Improve Sensitive Habitat and Movement Route Connectivity for Colorado’s Big Game Species, encouraging the BLM to adopt recommendations for managing land use development in big game important habitat”[41]

With the Plan, CPW has the ability to provide clarity about the lack of a relationship of nonconsumptive recreational activity and wolves and has chosen not to do so despite decades of input from CPW on federal lands issues and litigating this broad authority as well. This is totally unacceptable. This failure to act would create huge impacts as the Organizations would have to reinvent the proverbial wheel every time discussions around wolf and herd populations are undertaken on a nonconsumptive recreational planning effort. These are exactly the type of impacts that Proposition 114 requires be resolved in the Plan and CPW has consistently asserted it has authority to manage across the state. We would request similar clarity for nonconsumptive recreation be provided for in the wolf plan as has previously been provided for in wolverine planning docs.

2(a)(3). Internally conflicting positions on CPW involvement on federal lands are taken within the Plan.

The scope of CPW’s statutory authority to manage and guide wildlife on federal lands is also an issue that is inconsistently addressed within the Plan. Portions of the Plan appear to just concede existing jurisdiction for management of wildlife on public lands, while at other points in the Plan CPW clearly states the importance of public lands to wolves. There is no analysis or discussion of why directly conflicting positions are taken on the management authority of CPW on public lands.

Despite the value of the Plan in subsequent federal planning efforts, portions of the Plan try to avoid addressing federal lands as follows:

“.. Federal land management agencies have sole management discretion over their lands. CPW has no legal authority to implement restrictions or land management prescriptions on lands it does not own or lease. Therefore, it will be important for federal agencies and CPW to collaborate on land use issues as they relate to wolf management, which may include recreation, grazing management, public access, or habitat manipulation. CPW will facilitate on-going collaboration with Federal land managers in instances where wolf presence or behavior may warrant temporary public land access restrictions.”[42]

While the Organizations are very concerned that the above provisions assume that closures will be necessary to protect wolves and we must again ask how this decision was made our concerns are much larger than just closures. When the above provisions asserting no authority to issue guidance on federal lands is compared to other Plan provisions, the systemic internal conflict of the Plan is immediately apparent. Conflicting provisions in the Plan would be represented by the following provision:

“Managing Impacts

-

- If wolves are creating conflict, manage to resolve the problem….

- Successful wildlife management includes both public and private lands, providing, where possible, consistency of management across land jurisdictions.”[43]

The Organizations are unable to identify how these asserted distinctions on CPW authority on public lands could be justified in the Plan. These provisions directly this conflict with each other. These conflicts opens a proverbial pandora box of issues around pre-decisional issues when applied to access and asserts closures of public lands will be necessary. Have the federal planners already made this decision? We are not aware of it and if a route has been opened with NEPA it must be closed with NEPA as well. Wouldn’t this plan be a major tool in working with federal managers to avoid closures? We think it would. These types of conflict must be corrected in the Plan and guidance materials must be developed that apply consistent guidance for all types of usages that will be impacted by conflict from the Wolf reintroduction.

2(a)(4). CPW position of limited management authority on federal lands is directly contrary to the CPW position in the 10j designation request to USFWS for the wolf reintroduction.

The Organizations are deeply concerned about the many factors in the Plan that are dealt with in a very inconsistent and directly conflicting manner to internal CPW authority and efforts. This will create a myriad of problems in related actions for wolf management. The Organizations are very concerned the asserted lack of management authority for wolves on federal lands made by CPW in the Plan is directly contrary to the request by CPW for the 10j Rule from the USFWS. Pursuant to the CPW requested federal rule making commenced by the USFWS for the 10j designation, CPW identifies the basis for the request as follows:

“As part of the reintroduction and management planning process, the State has requested that the Service designate an experimental population under section 10(j) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973. We are considering promulgating a section 10(j) rule to address components of the gray wolf restoration and management plan being developed by the State of Colorado.”[44]

The Organizations are unable to reconcile assertions that CPW has limited or no authority over wildlife on federal lands with the request from CPW to assume more management authority over wolves on federal lands. We also can’t overlook the fact that CPW requested something from a federal lands manager and the federal agency actually did it. Again, the CPW request is sought without limitations and this request is also the same management model that has been applied to by most western states managing significant populations of wolves. This must be reconciled and corrected as CPW should not request management authority for the species and also assert that they lack jurisdiction to manage the species in the manner they are requesting. This type of consistency of management standards across state lines is significant. This type of consistency is an issue CPW falls well short of keeping pace with other states on.

2(b)(1). Obligations and resources created through CPW collaboratives must be recognized as well.

The basic authority of CPW is provided in Colorado statutes has been expanded by numerous commitments made in collaboratives initiated by CPW and a large number of management resources have come from these efforts. These collaborative obligations sought to provide information on a wide range of issues including wildlife and recreation from CPW with support of the nonconsumptive recreation community and also federal land managers and local governmental interests. These efforts create obligations outside the direct scope of the Plan and management resources that must be recognized in the Plan. These commitments also include compliance and consistency with existing statutory requirements but also these CPW led efforts have created a partnership environment for each group to be working under.

When we entered into many of these partnerships, it was our understanding that these collaboratives were being approached by CPW and everyone else with the mentality summarized by President John F. Kennedy as follows:

“As they say on my own Cape Cod, a rising tide floats all boats. And a partnership be definition, serves both partners, without domination or unfair advantage. Together we have been partners in adversity, let us also be partners in prosperity.”[45]

Put another way, collaboration is a two-way street. The Organizations have satisfied our obligations under these partnership efforts, often through huge commitments of time and resources on issues that may not directly impact our concerns. Based on the numerous assertions and promises made throughout these collaboratives, the nonconsumptive community expected CPW to satisfy their obligations made in these collaborations in the future as well. It is from this foundation of collaboration that the Organizations must voice strenuous concerns to the several Plan provisions that seek to avoid issuing public land management guidance on nonconsumptive issues despite subsequent provisions where the need for public land management is recognized and provided. Silence in the Plan sends a message and that cannot be overlooked. Blanket assertions of closures as a primary management tool also sends a message to the nonconsumptive recreational community despite CPW developed resources that outline a detailed incremental management process before closures, and that cannot be overlooked either. Right now, our two-way street of collaboration only has travel flowing one direction.

The number of CPW collaborative efforts the Organizations participate in are simply too long to list. Several of these efforts are statewide and warrant a brief discussion, as the Organizations have fulfilled our obligations under these collaboratives. One effort would be the CPW/DNR COOP whose mission is outlined in Governor Polis Executive Order B 2020 008 as follows: