Public Comment Processing

Att: FWS-R6-ES-2023-2016

US Fish and Wildlife Service MS PRB/3W

5275 Leesburg Pike

Falls Church, VA 22041-3803

RE: Proposed Wolverine Listing and Updated Assessment, Docket No. FWS–R6–ES–2023–0216

Dear Sirs:

Please accept this correspondence as the comments in vigorous opposition to the Proposed listing of the wolverine and updating of the species status assessment addendum(“The Proposal”) from the Organizations. Our opposition to the Proposal is not a position we take lightly or without thought as the motorized community has been supporting wolverine and related species research for several decades. Our support has included direct funding of research and donations of equipment for researchers. When those researchers have run into trouble in the backcountry while performing their research, we have been the members of the public that recovered broken equipment, stuck riders, and provided other indirect support for the researchers. This research partnership has spanned almost a decade with the hope of identifying the relationship between wolverine populations and recreation in all forms. Given the relationship we have had with globally recognized leaders in research of wolverine challenges, we are intimately aware of the lack of relationship between wolverine populations at the landscape level and dispersed motorized recreation as this has been the basis of extensive candid discussions.

We are disappointed the Proposal twists what has historically been a good partnership working towards solutions for the species and several other species into an overly political and highly charged discussion again. Rather than recognizing the decades of research that has failed to establish a relationship between wolverine populations and dispersed recreation , the Proposal simply asserts that research has never been undertaken. This position could not be further from the truth but rather directly evidences one of the most glaring failures of the Proposal. Inconclusive research is simply not the basis for listing but is rather an indication that the relationship being researched does not exist. In direct contrast to the efforts, we have undertaken to support research, where we have worked hard with researchers to clearly identify challenges or conclusions to benefit the species. The Proposal often entirely misquotes conclusions of works, ignores other research entirely, applies legal standards in a completely inconsistent manner to create what can only be summarized as a worst-case scenario for the wolverine in order to support a possible listing. This is frustrating and disappointing to us as we have decades of effort supporting high quality research to try and resolve these questions and results in a listing decision that is largely indefensible on the merits.

Our opposition to the Proposal is based on both the poor level of analysis provided on the wolverine as this will not benefit the wolverine. Our opposition is also based on the horrible precedent that it is setting as an ESA listing should not be based on an inability to establish a relationship after years of research. ESA listings must identify actual significant threats to the species and address those challenges. Arbitrarily elevating political concerns outside the species will never protect the species or remove it from listing. A listing decision must be based on best available science and not the arbitrary creation of a fact pattern that is now being made to support previously made decisions. We are concerned that the result of this effort will be an immense amount of conflict in any planning effort that will generate no benefit for the species.

While we are opposed to the listing based on the lack of credible science, the decision not to designate critical habitat is supported as there is no change in population trends and many researchers have determined that populations are increasing. Until arguably accurate population counts can be created, and far more accurate information can be identified regarding the life cycles of the species, there is no reason to designate critical habitat.

Who we are.

Prior to addressing the specific concerns, the Organizations have regarding the Proposal, we believe a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization of approximately 250,000 registered OHV users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations. The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a largely volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands. Colorado Snowmobile Association (“CSA”) was founded in 1970 to unite the more than 30,000 winter motorized recreationists across the state to enjoy their passion. CSA has also become the voice of organized snowmobiling seeking to advance, promote and preserve the sport of snowmobiling through work with Federal and state land management agencies and local, state and federal legislators telling the truth about our sport. CORE is an entirely volunteer nonprofit motorized action group out of Buena Vista Colorado. Idaho Recreation Council (“IRC”) is comprised of Idahoans from all parts of the state with a wide spectrum of recreational interests and a love for the future of Idaho and a desire to preserve recreation for future generations. The Idaho State Snowmobiling Association (“ISSA”) is an organization dedicated to preserving, protecting, and promoting snowmobiling in the great state of Idaho. Our members may come from every corner of the state, but they all share one thing in common: their love for snowmobiling. Our mission is to keep trails open for all users to enjoy. For purposes of these comments, TPA, CSA, CORE, IRC, ISSA and COHVCO will be referred to as “the Organizations.”

2(a). Wolverine research and its support by the motorized community.

The motorized recreational community across the country has been actively supporting wolverine and lynx research for more than a decade to address the lack of data on wolverine and lynx response to all forms of recreational activity. This concern was identified more than a decade ago. These efforts have included efforts by globally recognized species experts such as Jeff Copeland, Bob Inman and John Squires. Our efforts have also included years of involvement in Colorado’s lynx blueprint effort and wolverine reintroduction discussions. These meetings partially drove our increased involvement with the wolverine research and addressed many issues that are simply dismissed in this Proposal, such as the ability of avalanche mitigation work to impact denning wolverines, who frequently den in avalanche chutes. These possible incidental take issues were of significant concern for DOT and ski areas that performed significant avalanche mitigation but was not a concern for dispersed recreation as we did not do this work. Rather than addressing this issue, developed ski areas are simply excluded as possible impacts and avalanche mitigation efforts are never mentioned. As parts of this effort, we have been able to identify management standards to protect individual denning wolverines from all recreational risks with implementation of standards such as temporary closures around confirmed denning sites for all recreation activity.

The wide-ranging support of the motorized community for these efforts have been specifically recognized. The Idaho State Snowmobile Association was a recognized partner on years of research on the relationship between recreation and wolverine populations as follows:

“We are grateful to our multiple partners and collaborators who have assisted the project in numerous ways. Funding and equipment for the project has been contributed by the US Forest Service, Southwest Idaho Resource Advisory Committee, Southeast Idaho Resource Advisory Committee, Round River Conservation Studies, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Idaho State Snowmobile Association, The Wolverine Foundation, Sawtooth Society, Central Idaho Recreation Coalition, Brundage Mountain Resort and the Nez Perce Tribe.”[1]

The motorized community has also been very involved in supporting cutting edge research that provided real time feedback on the response of species to all forms of recreation outside the work of the wolverine foundation. Our efforts have supported ground breaking research in Colorado, which was again recognized as follows:

“We thank W. George for valuable assistance with preliminary data analysis, the many field technicians that distributed GPS units to recreationists, the participants who volunteered to carry the GPS units, the outfitters and guides who agreed to carry them, and the local FS offices for providing logistical support and information about the area.”

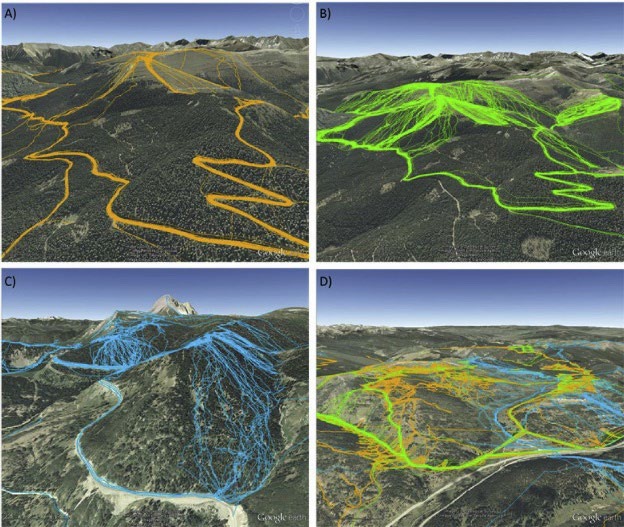

This research yielded immediately identifiable data that could be broken down by user type and lynx location as exemplified by the following charts:[2]

Fig. 2. Examples of recreation tracks recorded with GPS units during the study in western Colorado, 2010e2013. Panel A) snowmobile tracks primarily on trails in the Vail study area, B) hybrid skiing in the Vail study area; thick lines near the bottom of the picture show snowmobile travel, while thinner dispersed lines further back show skiing, C) backcountry ski recreation in the San Juans study area, and D) a combination of all three recreation types at the Vail study area, showing areas of overlap as well areas used primarily by one recreation type. Image credit: Google, DigitalGlobe.”

It is deeply troubling that the Proposal fails to even discuss the inherent conflict in this research being available as use of this model of research was specifically requested by Barrueto. This model of research not applied by Barrueto but he was seeking to perform this research in the future. We have participated in this effort and can state with certainty it is not expensive or difficult to perform currently. With the listing of the species, collaborative efforts on research like this will simply cease to exist. This impact should not be overlooked and has also been the basic of extensive scholarly discussion.[3]

The involvement and support of the motorized community in supporting this research forces us to ask many basic questions unrelated to recreation and much more closely related to the basic process on how the Service can drive and support the development of research processes like these. These processes are critical to the implementation of management that actually benefits the species. One step the Service can do in supporting research such as this is to lower the reliance on less developed and accurate methodology for the listing of species rather than making failed foundational efforts such as this a cornerstone of listing decision. This basic step to improve underlying processes has failed to be taken in the Proposal, as rather than addressing this groundbreaking new work and facilitating its expanded usage, the Proposal continues to be based on largely anecdotal evidence that is then supplemented with layers of supposition and conjecture. While the failure of some researchers to apply best available scientific methods is concerning, the adoption of such flawed research methodology by the agency as the sole basis for species listing is astonishing.

The systemic failures of the basic scientific, rulemaking and listing process has resulted in decisions that are highly predecisional and arbitrary in nature. The Proposed listing provides for impacts far wider ranging than merely using reasonably research methodology. The listing seeks to create the ability to unilaterally interpret research data and unilaterally and allow the Service reach conclusions of their own without regard to the conclusions of the researchers. This is hugely problematic as this will alter the flow of research and data and silence research that could conflict with a future listing. This type of data on issues is critically important as any researcher that may contradict a conclusion must provide peer reviewed and published data to support their decision as to why a factor is or is not a priority for management. If the Service can subsequently revise data and conclusions of researchers to support a predecisional listing decision, the value of the scientific process is entirely lost. This is far more of a concern than the listing of any species could ever be as the only way to protect a species is to truly identify threats to the species without political pressure so they can be addressed.

The conflicts that have resulted from the cavalier nature of the update of the listing decision is also reflected in the completely inaccurate summary of the current efforts for a species reintroduction in Colorado. Another concerning failure of the Proposal, astonishingly inaccurate summary of current Colorado status of species, which the Proposal summarizes as follows:

“Colorado Parks and Wildlife had previously considered reintroducing wolverines to Colorado as a nonessential experimental population to further their conservation (see 78 FR 7890; February 4, 2013). However, that proposal was withdrawn in 2014, when we withdrew our proposed listing rule (see 79 FR 47522; August 13, 2014). There is currently no formal proposal to reintroduce wolverines to Colorado.”[4]

The complete conflict of this position with even the CPW website on the wolverine is immediate as the CPW website on the wolverine provides the following summary:

“Wolverines have been extirpated from Colorado, but Colorado Parks & Wildlife is in discussions with partners and stakeholders about the potential to restore this species to Colorado’s High Country.”[5]

Even basic research into this situation would have resulted in awareness that on every CPW Parks and Wildlife Commission meeting to occur over the last year a wolverine reintroduction update has been provided to the public. Colorado Legislature is also developing legislation to allow the reintroductions of wolverines to occur in the State as well.[6] With failures of basic information such as this, the Organizations must oppose the listing and update as foundational information on the Proposal simply has not provided or has not been obtained.

2(b) The Colorado situation evidences why scientific process matters as actions that may warrant incidental take authorization from the Service are simply not mentioned in the listing.

As noted the motorized community has been involved with wolverine discussions for more than a decade, we are aware of significant issues that may warrant an incidental take authorization from the Service for operations. Many of these incidental take issues simply are not mentioned despite the critical public safety efforts that could be stopped without an incidental take authorization. Avalanche mitigation efforts are commonly performed by State Departments of Transportation for public safety and performed by ski areas for the safety of those users. Avalanche mitigation efforts were a primary concern for possible wolverine impacts as female wolverine are most vulnerable to this type of action as they tend to den in avalanche chutes due to the deeper and more persistent snow. This results in female wolverine mortality being disproportionally impacted by avalanche mitigation efforts. We have attached selected documents from the Colorado stakeholder meetings on the wolverine in 2011 addressing these concerns and how an incidental take permit could address these issues. These are serious concerns for our members and should be addressed in the listing. Avalanche mitigation efforts with transportation infrastructure simply are not mentioned at all and ski areas are simply summarily dismissed as a possible threat.

Again, the Organizations must question how issues such as the need to issue incidental take authorizations for avalanche mitigation efforts directly killing denning wolverines was not recognized as an immediate problem. It was one of the first things that came up in the Colorado effort and we are not aware of why an incidental take would not be authorized in this situation. While these are efforts that are generally not performed by the snowmobile community, these efforts provide significant value to our membership and warrant protection.

2(c) Carcass management has been hugely effective in protecting all species but is not mentioned in the listing as a noncontroversial tool to protect wolverines.

As noted previously the Organizations were active participants in the 2011 Colorado effort to reintroduce wolverines. Several of these meetings addressed successful efforts undertaken by CDOT in protecting wildlife, such as wildlife overpasses, fencing and active carrion management plans by CDOT. Many of these tools benefitted multiple species at significant levels. CDOT efforts with wildlife overpasses have been hugely successful in protecting deer, elk, lions and every other species that must cross an interstate.[7] Clearly these are tools that would protect a species like wolverine, and if we assume these population estimates that are in the listing. For the sake of discussion if these estimates are accurate wouldn’t these be primary tools to protect wolverines from direct mortality as even the loss of one animal could result in a significant percentage decline in the population. Instead of focusing on tools like this the listing continues to focus on anecdotal concerns supplemented with layers of theory and supposition that may never result in any benefit. This is a concern and causes us to think the Proposal is politically driven rather than seeking to protect the species.

While we are aware that building overpasses and miles of fencing is expensive, CDOT also shared their high levels of success in protecting predators, like lynx, fox, and lions by simply removing carrion from roadkill in a more timely manner. CDOT managers found that the removal of these carcasses removed the desire for predators to investigate these as possible food sources along interstates. Their research found that species like lynx and lion moved through the areas surrounding the interstate much more quickly and as a result were far less apt to be struck by a motor vehicle. These preliminary conclusions provided by CDOT were recently confirmed by researchers who found wolverine, lynx and other omnivores spend significant time at carrion sites. [8] This research indicated this behavior may create a host of new management issues and challenges, only confirming the preliminary data from CDOT almost a decade ago. Given that wolverine are well known feeders on carrion, wouldn’t a step like addressing roadside carrion in wolverine habitat be effective for protecting the species and highly efficient in achieving these goals? Again, this is simply not discussed despite recent research indication wolverine behavior is heavily influenced by the presence of carrion.

2(d) Ski area management was historically a primary topic of management concern and was simply removed from Proposal.

The Proposal fails to provide any basis for the altered management of wolverine in relation to ski areas operations. The treatment of developed ski areas in the Proposal stands in stark contrast to the position of the Service clearly expressed in the Colorado stakeholder efforts in 2010 & 2011. These professionally facilitated meetings spanned more than a year and were consistently attended by 30 plus people.[9] As noted previously the snowmobile community was heavily involved in Colorado based wolverine workshops where possible impacts of human activity on wolverine populations looked VERY different from the Proposal. As discussed in more detail in the attachments, ski area operations were a major concern for the ski area operators, the Service and CPW. As a result of this ambiguity, we spent extensive time exploring incidental take authorizations and other tools to provide clarity for ski areas in this process. While the Proposal asserts to be applying new research, we must ask what new research was published to support removal of all ski area operations as a threat or possible need for an incidental take authorization? This process would be highly valuable to our interests as it is clearly highly effective in removing functionally similar activities as possible threats to the wolverine. We would like to apply this model of research immediately.

We must ask what is the basis for this change, the extensive discussions that occurred after these wolverine workshop meetings which only compounds this question as ski area operations are a priority concern in every USFWS analysis document prior to the Proposal. The concern for possible impacts from developed ski areas was summarized in the 2013 listing as follows:

“Preliminary results from an ongoing study on the potential impacts of winter recreation on wolverines in central Idaho indicate that wolverines are present and reproducing in this area in spite of heavy recreational use, including a developed ski area, dispersed winter and summer recreation, and dispersed snowmobile use (Heinemeyer et al. 2012, entire).”[10]

The 2018 Science update on the wolverine was FAR less than compelling basis to determine there was no relationship between ski areas and wolverine in its summary of the analysis of ski areas which provides as follows:

“They also reported that wolverines responded negatively to increasing intensity of winter recreation, with off-road and dispersed recreation having a greater effect than recreation that was concentrated on access routes (Heinemeyer et al. 2017, p. 34). In addition, wolverine avoidance of roads and groomed areas used by winter recreationists was less than estimated for dispersed recreation, suggesting that wolverines may be less sensitive to predictable winter recreation use patterns (Heinemeyer et al. 2017, p. 40).”[11]

The 2018 Survey for the wolverine also clearly stated that all recreational activity maybe a concern as follows:

“However, this research also found that wolverines maintained their home ranges within areas with relatively high winter recreation activity over several years of monitoring, including some areas found to contain the highest recreational activities (Heinemeyer 2016, pers. comm.). The study has not been able to determine whether these resident wolverines are reproductively successful due to the limited monitoring information available for reproductive females (Heinemeyer 2016, pers. comm.).”[12]

The comical amount of ambiguity in this position on winter recreation is immediate as we are aware of numerous heavily used winter recreation areas existing within wolverine habitat. We are also aware of numerous snowmobile recreation areas that have visitation levels that exceed adjacent ski area levels of visitation. We are unable to even theorize what “relatively high winter recreation activity” even means as a standard, making any discussion of levels of usage between these two issues impossible. The Organizations are also aware that some back country opportunities on ski areas include much lower intensity opportunities such as cat skiing, hybrid skiing and human powered opportunities. These opportunities are provided at low levels of intensity of usage. This is another indication that information is not accurately conveyed in the Proposal and the limited information that is applied is simply arbitrary.

The arbitrary nature and failed decision making of the Proposal is exhibited by the 180 degree change in the basic level of concern around the management and operations of ski areas and possible impacts of ski area operations on wolverine. The Proposal summarizes the change in analysis for ski areas as follows:

“The analysis includes various studies concerning the effects of backcountry recreation on wolverine habitat. These studies looked at various types of backcountry recreation including skiing, snowboarding, snowshoeing, and snowmobile use. The studies found that wolverines avoided high quality habitats within their home range where these activities were occurring. The service is not concerned about the effects of winter recreation in established and developed areas such as ski resorts at this time”[13]

The Organizations would be remiss if it was not raised how any research was applied and related to how decisions were made in the Proposal appears less than accurate. The inference from this position is developed ski areas have MORE impact than a groomed route by itself. This creates a significant problem for the current Proposal, as it arbitrarily removes ski areas from further management while the lesser threat of dispersed recreation is elevated for management despite the large overlap in terms of the two activities on the ground. There are simply no discussions provided, or research cited, to address this change in management position on ski areas from the 2018 Science update

3a(1) Have the Terms of the Court decision driving this entire process been complied with?

As we have in these comments, the Proposal suffers from several basic foundational problems as it fails to accurately reflect clearly stated research conclusions and overlooks many other documents entirely. The poorly documented change in positions on so many foundational issues with the listing forces questions such as “Has the settlement been complied with?” The Court Decision driving this entire process clearly states the documentation standards for the future listing efforts as follows:

“The Service must rationally explain why the uncertainty regarding [a particular issue] counsels in favor of [one conclusion] rather than the opposite conclusion.”[14]

The Organizations must ask this question before even addressing more generally applicable standards. The settlement clearly sets a high standard for compliance with its decision. It is unclear if this standard has been complied with. It is our position the listing proposal has failed to comply with this standard.

3(a)(2) The Proposal ignores conclusions of researchers and simply reinterprets data to create a fictional theory to support the listing of the wolverine and predecisional management restrictions.

Two of the foundational objections from the Organizations regarding the Proposal are: 1. The relationship between wolverine populations and recreation had not been researched previously; and 2. The assertion that the relationship of recreational activity and wolverine populations has changed based on new research. Wolverine research is an issue the motorized community is intimately familiar with as we have partnered for almost a decade in research efforts on the species and possible negative responses of wolverine to human behavior.

It has been our position that the wolverine population is not impacted by human activity simply based on common knowledge, which we also knew was insufficient to support any decision making for a proposed listing. As a result, the inability of researchers to establish a relationship comes as no surprise. We simply never expected to find one. What is surprising the fact that recognized leaders in wolverine research have now concluded more vigorously and completely than ever before that the relationship does not exist and that statement is simply never mentioned in the Proposal. Even if research indicated there was a risk from human activity to the wolverine, this impact could be reduced to nonexistent levels with temporary seasonal closures around confirmed denning sites while they are in use. This situation should not be surprise as our community has effectively resolved problems for decades and the only way we can actually resolve the wolverine listing issue is by establishing an accurate count of wolverines and understanding what issues are impacting the species, is any and what issues are not impacting the species. The Proposal entirely fails to do this basic work.

Our partnerships have resulted in huge amounts of new ground breaking research on species of all types and we remain proud of these efforts as they have benefitted the species and recreational users of all types. Our position on the wolverine historically is founded upon the open and free exchange of information, high quality research and the ability to discuss concerns, data and theories in terms of scales of threats and how they can be resolved if these relationships are significant. The Organizations are highly frustrated that the Proposal systemically takes peer review published research out of context to support a predetermined conclusion other than those clearly identified by the researchers in the publication. The Proposal simply ignores the conclusions of the researchers work it is asserting to rely on or simply provides an entirely inaccurate summary of the issue to support a conclusion that directly contradicts the conclusions of the researchers. This is entirely a violation of basic scientific processes and abuses the wild discretion the service has in addressing threats to any species and entirely outside legal requirement of listing being based on best available science. This failure is deeply troubling and regardless of the conclusion would be opposed by our Organizations.

The failure of the Proposal to even accurately address the conclusions of researchers starts with research that the Proposal uses a foundation for a lot of the analysis provided. The Proposal provides the following summary of researcher’s conclusions on the relationship between recreation and human activity as follows:

“A large multi-State analysis of winter recreation impacts in the Northern Rocky Mountains was published in 2019, indicating greater concern for impacts to wolverines than we found in 2018 and showing a negative functional response to the level of recreation exposure within their home ranges (Heinemeyer et al. 2019a, pp. 13–14, 17–18).”[15]

The Proposal refers to this research as the 2019a Heinemeyer research and the conflict between this summary and the conclusions of the research are immediate and unresolvable. The 2019a Heinemeyer publication actually specifically provides highly important context and scale to their entire analysis around human activity. The 2019a Heinemeyer research states the context for their discussions as follows:

“The importance of dispersed motorized recreation to male wolverine resource selection ranked 10 out of 13, while avoidance of dispersed non-motorized recreation was similar to females at a rank of 6. Avoidance of linear recreation by male wolverines was marginally insignificant (P = 0.056) and of lowest importance (Table 4).[16]”

The Listing Proposal cites to the Heinemeyer 2019a study 15 separate times. The Science update cites to Heinemeyer 2019a an additional 15 times. Given this work is cited 30 times across the consolidated documents provided by the Service, this clearly identifies the significant weight of work the Service has placed on this work to the listing. This would lead to the conclusion the listing has reasonably accurately reflected this research in their documents. That assumption would be entirely incorrect.

The Organizations are unable to distinguish how the conclusions of this work could be aligned in any other manner than supporting the conclusions of the 2018 SSA about the minimal concern for general human activity and wolverine populations. Dispersed motorized recreation ranking 10th out of a possible 13 threats to the species overall is clearly not greater concern in the 2019a research when compared to the 2018 SSA. Any assertion of greater concern is further undermined as human activity for male wolverines was the lowest factor analyzed. Rather than being greater concern this is clearly supporting the identification of recreation and human activity as a low priority threat as stated in the 2018 SSA. Clearly this research is insufficient to support any assertion that the only response from wolverines regarding motorized recreation is a management concern as females showed more response to nonmotorized recreation in comparison to motorized recreation. This is certainly not sufficient research to support any management decisions or elevation of threats from recreation to the wolverine as the Service moving a 10th place finisher to 1st place is an astonishing feat even today.

Understanding the context for the discussion in the Heinemeyer 2019a research creates significant problems for the assertion of greater concern expressed in the Proposal when it is accurately summarized. These types of conflicts only explode when the full scope of subsequent research is actually addressed. Heinemeyer 2019a is also not the largest group of researchers to be unable to find a significant relationship between human activity and wolverine populations after years of work. In 2020 a coalition of 17 global leaders in wolverine research, representing every state in the lower 48 that have wolverine populations, specifically concluded that they were unable to establish any relationship between all human activity and wolverine populations. This conclusion was specifically outline as follows:

“We found no association with vegetative productivity, human disturbance, and habitat patch size. Our sampling design may have limited our ability to detect those effects because the sampling frame was based of models of predicted wolverine habitat. The models placed the sampling frame in areas with higher elevations, less human disturbance, and more forest than the 4 states surveyed contain in general. The restricted range of covariate values observed may have had more influence on the lack of importance than any other reason. In addition, the scale of the sampling cell, 15 km × 15 km, also averages over a large area of variable conditions; therefore, single values of co variates at that scale may show dampened relationships as compared to e-scale resource selection.”[17]

This research is not even mentioned in the Proposal, which is astonishing as the Proposal cites to other works by Lukacs addressing climate change and water resources. A complete copy of this article is attached to these comments as Exhibit 5. The direct and unresolvable conflict between the Proposal’s assertion that greater concern has been shown in subsequent research for human activity impacts on wolverine simply cannot be aligned with this work. The total inability to align this work with the Proposal conclusions and its complete omission from the document cannot be overlooked.

The Proposal systemic failure to address research accurately on recreation is again exhibited in the Proposal summary of the work by Mack and Hagan, which appears to be supplementing the work around the modeling of wolverine habitat published by Lukacs during the same time frame. The Proposal summarizes the Mack and Hagan work as follows:

“Additionally, new research found an incremental loss of wolverines in portions of central Idaho where winter recreation impacts are increasing (Mack and Hagan 2022, p. 13).”[18]

The immediate failure of the Proposal to support this position with best available science is evidenced by the fact the only citation to a work of Hagan is completely inaccurate in the supporting documentation. The only authority reference to a work of Hagan in the Proposal provides this as follows:

“Lyon, L.J., E.S. Telfer, and D.S. Schreiner. 2000. Direct effects of fire and animal responses. Pp. 17–24 (Chapter 3) in Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna [J.K. Smith (ed.)]. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42-Volume 1. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; Ogden, Utah. 83 pp. Mack and Hagan 2022”

The Proposal failure on this summary is immediately evidenced by the fact the cited work never addresses wolverines or recreation but addresses wildfire impacts on species in a chapter addressing fire and fauna. Candidly this relationship is so completely inaccurately summarized as to state recreation is not even mentioned in this chapter of the general technical report from 2000. This is a concern.

The Proposals failure is immense and unresolvable on these works as Hagan and Mack have performed wolverine research, which are a series of annual reports from Idaho Fish and Game that continued research of wolverine populations spanning more than a decade historically. We are aware of this relationship as we helped fund the previous research lead by Heinemeyer. These annual reports do not draw conclusions but rather provide raw data on individual wolverine that had been previously tracked after the conclusion of the other larger efforts. These publications of Hagan and Mack are clearly labeled as preliminary finding by Idaho Fish and Game as follows:

“Findings in this report are preliminary in nature and not for publication without permission of the Director of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.”[19]

The immediate conflict of making listing decisions based on a publication that is clearly identified as “preliminary in nature” cannot be overlooked. Again, this is not greater concern. It is deeply troubling that the conclusions of this research are again inaccurately summarized in the Proposal as the population trends are noted as actually improving in the exceptionally small study area as follows:

“We detected 40% fewer individual wolverines with cameras in 2021 than the peak of 11 wolverines live-trapped and monitored during 2011. However, the number of individual wolverines detected with cameras in 2021 (6–7) was slightly higher than the winter recreation project’s last 2 years (5 individuals).”[20]

If we assume for the sake of argument that the Service properly used results clearly identified as preliminary for the basis for a listing, again the preliminary results are not even accurately summarized. The conclusions that the wolverine population has been recovering over the last two years entirely within the distinct population segment identified by the Service is never mentioned in the listing. Rather the Service chooses to inaccurately summarize the work to support problematic research obtained outside the DPS. This is an immense problem for the listing as it may not manipulate their decisions by unreasonably relying on certain sources to the exclusion of others and is disregarding scientifically superior evidence and sources.

The manipulation of research is concerning when viewed in isolation but this is compounded as scientifically superior works from the same researcher in the same time frame on the wolverine are entirely disregarded. Again, the Proposal has failed on this type of issue as Diane Evans Mack specifically published her conclusions with 16 other leaders on wolverine issues that they were unable to identify any relationship between human activity and wolverines populations based on this work and numerous other works. This publication is attached as the work of Lukacs et al that is attached to these comments as an exhibit. Again, this is a failure of the most basic processes associated with the scientific process or requirements to plan based on best available science.

The Organizations are aware that these preliminary reports provide no specific reason for the possible decline in populations and recovery in the analysis area. While no theory is provided for location fluctuations in this specific population, the landscape level conclusions of this work addressing research in all areas researched are specifically addressed as follows:

“In summary, we did not confirm with cameras the number of individual wolverines we expected on the PNF portion of our study area. During 2011, the peak year of the winter recreation study, 9 of the 11 wolverines captured were on the PNF. In 2014, 5 wolverines were captured there. In 2021, across the same locations, we could confirm only 4 animals. We did not confirm a male in the territory encompassing Hard Creek, Granite Creek, and Fisher Creek Saddle. We also didn’t confirm a female on the east side of Warren Wagon Road in the Lick Creek or Pearl Creek drainages, where, in 2011, 3 females were live-trapped. We did confirm 1 male in the Lick Creek corridor, although in 2011 there were 2 resident males there. Our results seem to corroborate what Heinemeyer and Squires (2014) described as significant turnover, with known territories potentially vacant. In contrast, wolverine activity on the BNF portion of our study area appeared stable. As occurred during the winter recreation study, we confirmed 2 individuals at Warm Lake Summit, with possibly a third. The Gold Fork camera added an individual wolverine outside of the scope of the winter recreation study.”[21]

Even without the published peer reviewed conclusions of this research published by Lukacs, the immediate conflict between the Proposal conclusion that human development is a threat could not be aligned with the specific reasoning and detailed analysis of this research. This conflict of conclusions only expands as the Lukacs/Mack conclusions are based on almost a decade of data, that the population of wolverine was stable and possibly expanding. At no point does this research address levels of human development or support any assertion the population had fallen by 40% in that area. Rather the information provides a significantly different summary of the population trends and fluctuations. It is the pinnacle of arbitrary decision making for the Service to cut and paste portions out of any work, reinterpret them into conclusions the researcher specifically disagrees with and then use this is as the basis for a decision.

Listings of species on the ESA and general land planning efforts must deal with some level of legal uncertainty almost all the time. Throughout the decades of effort on these issues, it has become clear that the inability to prove a theoretical relationship is not proof of the relationship but proof of the LACK of a relationship between two factors. Even outside land planning and species management, this has been a significant question society has struggled with the great philosopher Voltare stating this conflicted relationship as follows:

“The interest I have to believe a thing is no proof that such a thing exists.”

The conflict presented by Voltare is obviously present in the wolverine listing certain interests have concluded recreation must be impacting the wolverine as this position cannot be disproven. Not only has this conflict plagued actual resolution of challenges to wolverines and many other species, this inaccurate relationship has led the Service to fail to satisfy their burden of proof in listing a species and taking management actions. The ESA specifically requires proof of a relationship for management, which has driven the concept of best available science for research and the legal requirement that best available science must be used for listing. The current Proposal reverses this burden and is now saying the scientific conflict and inability to establish a relationship between wolverine populations and recreation is the reason for the listing. Now the burden is shifted to the motorized community to prove there is no relationship to avoid listing.

While the ESA does not provide a specific definition of best available science for the Service, the courts have been very active in resolving this standard. The US Supreme Court has provided the following definition of how best available science is to be applied in the management of public lands:

In so doing, the action agency must “use the best scientific and commercial data available.” 16 U.S.C. § 1536(a)(2). This empirical mandate ensures the law is not “implemented haphazardly, on the basis of speculation or surmise,” and thus “avoid[s] needless economic dislocation produced by agency officials zealously but unintelligently pursuing their environmental objectives.” [22]

The Supreme Court interpretation of best available science is immensely problematic for the listing, given the failure of the Service to accurately summarize almost every work cited or consistently apply previous decisions. Subsequent to the Supreme Court decision, Courts have provided significant additional guidance on the nature of best available science which they outline as follows:

- “The agencies may not manipulate their decisions by unreasonably relying on certain sources to the exclusion of others.

- The agencies may not disregard scientifically superior evidence.

- Relatively minor flaws in scientific data do not render that information unreliable.

- The agencies must use the best data available, not the best data possible.

- The agencies may not insist on conclusive data in order to make a decision.

- The agencies are not required to conduct independent research to improve the pool of available.

- The agencies thus must rely on even inconclusive or uncertain information if that is the best available at the time of the decision.

- The agencies must manage and consider the data in a transparent administrative process.”[23]

The immediate conflict between the analysis provided in the Proposal and every standard outlined by the Courts cannot be overlooked or overstated. Less than 6 months ago, the Courts again clearly stated worst case scenarios for a species are not the proper basis for decision making as follows:

“In this case, we decide whether, in a biological opinion, the Service must, or even may, when faced with uncertainty, give the “benefit of the doubt” to an endangered species by relying upon worst-case scenarios or pessimistic assumptions. We hold it may not. The ESA and the implementing regulations call for an empirical judgment about what is “likely.” The Service’s role as an expert is undermined, not furthered, when it distorts that scientific judgment by indulging in worst-case scenarios and pessimistic assumptions to benefit a favored side.”[24]

It is disappointing to even have to make this assertion but the listing is clearly a worst-case scenario for the wolverine, that violates almost every criterion that Courts have developed to identify and apply best available science. The foundational conflict between the conclusions that are asserted in the Proposal and the conclusions of globally recognized species managers research cannot be overstated.

3(a)(2) Congressionally designated areas have significantly expanded since 2013 but this in not addressed in the Proposal.

Throughout the Proposal there is a theory that dispersed, and most particularly motorized recreation is a threat to the species. The service recently has identified that 41% of Wolverine habitat is in designated Wilderness or subject to other prohibitions on motorized access, which is outlined as follows:

“For example, generally wolverines will benefit from wilderness area protections (calculated as 18 percent of the extent of wolverine occurrence and 41 percent of core wolverine habitats in the western United States (Service 2018, p.103));….. Several large National Parks contain core habitat for wolverines, including Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Glacier, North Cascades, and Mount Rainer National Parks. These areas are largely protected from development, although they may be impacted by winter recreation to varying degrees.”[25]

This situation immediately begs the question of how could there be a significant fluctuation in Wolverine populations with these levels of prohibitions already in place. The failures in analysis of the Proposal on the relationship of congressional protections and what is thought to be the primary threat to the species only compounds when Roadless Area designations are included in the calculations. Once the combined percentages of Roadless and Wilderness areas is addressed on USFS lands, the areas prohibited or restricted approaches almost 60% of the USFS lands. This creates an immense factual problem for the Proposal.

The designation of Wilderness since 2013 provides significant conflicts with any assertion the Proposal is applying new research or has been accurately updated. Even a brief review of this issue would have identified that more than a million acres of Wilderness have been added to the National Wilderness system since 2013. As an example of these designations would include:

- The 113th Congress added five new areas and over 279,00 acres to the system in two enacted bills;

- The 114th Congress which designated three new wilderness areas in Idaho;[26]

- The 116th Congress passed one law, designating a total of 1.3 million acres in four states; [27] and

- Dingell Act designated more than 263,000 acres of wilderness in 2019. [28]

The Organizations are simply unable to identify any discussion of how much of these areas were in occupied or unoccupied habitat for the wolverine, or even that any of these designations occurred. This is despite the repeated assertion that the Proposal has been updated to address changes since the 2013 Proposal. Clearly the expansion of existing protections on millions of acres of possible wolverine habitat should have been addressed as existing protections are a statutorily required analysis for any listing. We simply are unable to envision any interpretation of an update that would not address these changes in existing protections for habitat as this is statutorily required under the ESA criteria. This greatly undermines both the assertions that the 2013 Proposal has been accurately updated and that the Proposal is legally sufficient to list the wolverine.

3(b) Peer review of listing raises many foundational questions from global leaders in wolverine research but none are addressed.

The Organizations would be remiss if the utterly terrible nature of the peer review of the Proposal was not addressed in our comments. The Organizations are intimately familiar with several of the peer reviewers as we have worked on numerous projects that they are involved in leading or a researcher on. Sometimes we have disagreed with these researchers on resolutions to concerns but after significant engagement with these reviewers, we have found them to be exceptionally well versed on wolverine and lynx management issues.

We have found high levels of alignment in the fact that each of us was working towards developing a robust sustainable population of the species. This alignment of purpose is not found in the listing. The situation is highly frustrating and highly insightful to the mentality of the listing as the peer review raises real questions about foundational positions that are being taken, but none are even addressed. This makes us think the peer review was merely done to check a box and move on regardless of any input from the peer review. This is highly frustrating and a violation of among other specific provisions of the ESA, more generalized data requirements such as the information and data quality act of 2001, which specifically provides as follows:

“SEC. 515. (a) IN GENERAL.—The Director of the Office of Management and Budget shall, by not later than September 30, 2001, and with public and Federal agency involvement, issue guidelines under sections 3504(d)(1) and 3516 of title 44, United States Code, that provide policy and procedural guidance to Federal agencies or ensuring and maximizing the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of information (including statistical information) disseminated by Federal agencies in fulfillment of the purposes and provisions of chapter 35 of title 44, United States Code, commonly referred to as the Paperwork Reduction Act.”[29]

The USFWS guidance specifying the peer review process for their listing efforts identifies the issues and requirements as follows:

“The FWS definition of objectivity includes whether the disseminated information is presented accurately, clearly, and completely, and in an unbiased manner…. Transparency about research design and methods is pivotal to reproducibility. With regard to analytical results, we will generally require sufficient transparency about data and methods that a qualified member of the public could undertake an independent reanalysis. These transparency standards apply to our analysis of data from a single study as well as to analyses that combine information from multiple studies. However, the objectivity standard does not override other compelling interests such as privacy, trade secrets, intellectual property, and other confidentiality protections.”[30]

US Fish and Wildlife memo outlines the significant value in performing a peer review of research supporting a decision as follows:

“For instance, it might be possible to subject critical portions of the scientific materials to review, in advance of a decision. A major advantage of early review is the opportunity to take early corrective action. Most early drafts can be substantially improved through early informal reviews by internal or external experts. Improvements based on these early “friendly” reviews will lead to better products (e.g. study design, sampling method) and more useful comments during more formal peer reviews such as those mentioned above. Soliciting informal reviews by subject matter experts is a good idea (e.g., better products, broadening your scope of professional contacts) even if formal peer review is not applicable.”[31]

Clearly, the process outlined above is contingent upon some type of integration of this information into the final decision-making process. After reviewing the 9 pages of highly specific peer review of the draft Proposal and the final Proposal, we are unable to identify a single location where peer review was incorporated, despite these efforts being highly detailed and specific and generally scathing in nature. We will note several comments that are problematic to foundational positions taken in the listing starting with the assertion in comment #12 from Robert Inman that he is not aware of the most important paper in the listing foundation as follows:

“I had not seen the 2022 Barrueto paper before. This is a somewhat startling finding, a 40% decline in density over 10 years and in an area with significant protected (National Park) areas. The finding is stark enough to make me wonder if it passes the common‐sense test ‐ How can it be possible that a relatively protected population declined by that much, This is a stark enough decline that something new must have been going on in the area to cause it. What is new? Did trapping activity increase dramatically in the 10 year period? Unlikely that climate effects occurred.”[32]

This should have been a red flag for the Proposal as one of the global leaders in wolverine research was not aware of one of the publications that is foundational to the listing. This makes us think that prior to the listing this work was not well received or groundbreaking new research. The Organizations would ask the same questions on these provisions and we are unable to identify any revision of this provision to address what is a foundational concern in the listing. Robert Inman continues his peer review in comment # 23 as follows:

“Roads are at lower elevations and snow is greater at higher elevations. What if roads were the driver? If you take roads out, which the researchers did and the SSAA mentions, if you take roads out and then test for something inversely correlated with roads, what do you find ‐ that the thing that was inversely correlated is now “correlated”. Is that rigorous science?”[33]

Again, when a peer reviewer questions the rigor of the scientific process in the listing and its supporting documentation it should have been a red flag. This red flag was simply never addressed. Robert Inman concerns continue in comment #42 on the relationship between roads and wolverine impacts as follows:

“In our Yellowstone study, we documented numerous road crossings. We did not publish a paper on it but chapter 7 of our 2007 cumulative report has info on >100 road crossings.”[34]

Peer reviewer concerns on foundational issues with the Proposal are not limited to just Robert Inman. John Squires expresses serious concerns in comment 38 about the asserted impacts of roads and recreation on wolverine populations as follows:

“I don’t have science to back this statement, but I find it hard to believe that wolverines are avoiding forest roads during winter in Montana. During winter in central Montana, we observe wolverine tracking crossing roads almost every day across multiple study areas as we trap lynx, including groomed roads with heavy snowmobile traffic.”[35]

Peer Reviewer John Squires concerns about human development and wolverine populations continue in comment 41 where he states as follows:

“The one animal that was documented dispersing from Wyoming to the southern Rockies in Colorado crossed multiple highways, including 4‐lane. If you are stress the road/semi barrier issue you should mention the one dispersal to Southern Rockies that was documented, did cross highways.”[36]

While the peer review process is somewhat discretionary in how it is responded to, 9 pages of highly detailed and specific comments about the Proposal warrants some type of response. This systemic failure simply must be addressed and corrected. While we can support and fully understand disagreement of researchers on specific details or technical aspects of any work, as this is part of the basic scientific process, this level of conflict and disagreement is outside the norms of the scientific process and is evidence of significant underlying problems with the proposition being forwarded.

3(c) It is horribly predecisional to move a previous listing forward with significant alterations in factors involved in the basis for listing without analysis of these changes.

The Organizations are very concerned that the entire process was horribly and completely Predecisional in its application. As the Organizations have previously addressed, any assertion that the changes are simply based on new research is problematic factually and legally. While the Proposal asserts to move the 2013 decision forward and update the science, the Proposal is something very different as the current proposal seeks to alter basic decisions such as the scope of the distinct population segment without updating the validity of that decision for 2023. The Proposal further seeks to move possible threats to the species from uses that were of such low risk as to be specifically addressed for protection in the 2013 listing and moves portions of them to primary threats to the species.

3(c) It is predecisional to adopt a 2013 listing based on a lack of legal protections in Canada without addressing significantly expanded legal protection of Canadian wolverine since 2013.

The predecisional nature of the Proposal is again evidenced by the fact that the 2013 listing proposal was based on the limited or lower protections available for wolverine in Canada. The 2013 listing continued to apply ESA criteria to the declining populations in Canada, as exemplified in the following quote:

“Causes of these changes are uncertain, but may be related to increased harvest, habitat modification, or climate change.”[37]

The continued applicability of concerns such as this must be recognized in the Proposal as major change in listing status of wolverine in Canada in 2018.[38] While this is uniformly recognized as a major change in Canadian management of the species it is never addressed in the Proposed listing despite this change being highly relevant to possible impacts to population sizes of wolverine in the research area of the Barrueto. The myriad of factors that are addressed in the Canadian listing are FAR beyond the scope of the proposed US listing as most wolverines are in the artic circle region of Canada and that population is doing well. The Canadian management of wolverine also must address many tribal issues in the management of the species, which may negatively impact the species. This again warrants discussion in the Proposal given the significance of this difference to the 2013 listing. This again has not occurred.

The predecisional nature of the Proposal as presented is significant and evidenced by the conflict in the Proposal in the treatment of Canadian regulations of the wolverine in the Proposal. If the Proposal was viewed in isolation, one could conclude that there has not been any changes in Canadian management efforts for the species. This is simply inaccurate as the Canadian Committee for the status of endangered wildlife in Canada significantly revised their regulations in 2018. The recovery plan for the Eastern Canadian wolverines was completed in 2016.[39] Clearly these are major regulatory changes that should be addressed in any management plan given the significant of this distinction in planning for US wolverine management.

The 2013 USFWS listing found the international boundary significant in the listing concluded as follows:

“In our 12-month finding for the North American wolverine DPS (75 FR 78030) we conducted a complete analysis of the discreteness of the wolverine DPS that we incorporate here by reference. In that analysis we concluded that the international boundary between Canada and the United States currently leads to division of the control of exploitation and conservation status of the wolverine. This division is significant because it allows for potential extirpation of the species within the contiguous United States through loss of small populations and lack of demographic and genetic connectivity of the two populations. This difference in conservation status is likely to become more significant in light of threats discussed in the five factors analyzed below…… Existing regulatory mechanisms are inadequate to ensure the continued existence of wolverines in the contiguous United States in the face of these threats. Therefore, it is our determination that the difference in conservation status between the two populations is significant in light of section 4(a)(1)(D) of the Act, because existing regulatory mechanisms appear sufficient to maintain the robust conservation status of the Canadian population, while existing regulatory mechanisms in the contiguous United States are insufficient to protect the wolverine from threats due to its depleted conservation status.”[40]

The myriad of problems presented by application of the 2013 USFWS position in 2023 cannot be overlooked as many of the conclusions reached in 2013 were factually problematic. Aligning the 2013 decisions with subsequent changes in management would be difficult. We do not contest its possible validity for Canadian management responses but this relationship is not a US decision as wolverine are listed as a species of Special Concern in Canada and separately listed for ESA purposes in the United States. Canadian efforts have also included the release of a recovery plan for the eastern populations of wolverine in Canada and heightening of regulations in 2018 with another round of management changes for the western Canada wolverine. Wolverines are also threatened in Ontario under the Ontario Endangered Species Act in 2007 which has also conducted on-going management efforts.

The need to address changes in Canadian management decisions made in response to possible population declines is exemplified by the conclusions of the Barrueto research, which was levels of trapping of wolverine in the area were simply too high to be sustainable. It is important to note that wolverine trapping has not been permitted in the US for decades. Clearly additional restrictions on trapping in the US would have been unwarranted as US regulations prohibit trapping and only allow for incidental take permission for trapping of other species. Clearly the Service was pressured to do something to protect wolverine, which only drove the two management models further into conflict with each other. The relationship between the US listing and Canadian management plans issued after the previous listing is the immediate conflict between management concerns in the two efforts. Canadian management plans entirely fail to recognize dispersed recreation as a management issue, rather focusing on factors such as timber and mining as priority threats.[41] This immediately begs the question of why was this overlooked? The only rational conclusion is the possible impacts to wolverine from recreation are so minuscule as to be disregarded in the plan. If alignment of these regulations is the goal of this effort, alignment of management responses must be addressed as well. We simply cannot accept what is identified as a primary threat in the US is largely unregulated in Canada for the same species. But we must question any relationship to the US management situation, which has not changed. The predecisional nature of the Proposal on this fact is furthered by the decision of the Canadian government that dispersed recreation is of such low threat to the species as to not even warrant analysis.

4(a) There is a staggering lack of information on the species including basic population estimates and agreement on population trends in the Proposal.

The arbitrary nature of the Proposal is again evidenced by the wide range of population estimates that have been involved in the management of wolverines. The wide range of estimates regarding the population of wolverines in the lower 48 states result in problematic application of population estimates and asserted declines in Canada. This is concerning as establishing some type of baseline of existing population is necessary before any assertion of a possible decline in the population could be made. The immense ambiguity of population estimates in the contiguous 48 states is concerning as this range is outlined as follows:

“The precise size of the wolverine populations in the contiguous United States are currently unknown but may be small due in part to their large territories and the limited amount of available habitat in the contiguous United States. Estimates based on extrapolations of densities and suitable habitat suggest there could have been approximately 318 wolverines (95 percent CI = 249–926) in the contiguous

United States more than a decade ago (Inman et al. 2013, p. 282). The best available estimates of effective population size of wolverines in the contiguous U.S. portions of the Northern Rocky Mountains and North Cascades are likely fewer than 50 combined (Schwartz et al. 2009, p.3226).”[42]

Again, this assertion of the Proposal is problematic as most states are not providing population estimates for wolverines in their boundaries. The lone state providing populations estimates is the state of Idaho, which provides a summary that is in direct conflict with an assertion of population collapse, is as follows:

“Wolverines naturally occur in low densities across their global range. Current western U.S. population estimates range from 250 to 318 individuals, reflecting the estimated population prior to European settlement. These levels suggest that wolverines have reclaimed large expanses of their historical range in the contiguous U.S. after historical lows or local extirpations in the early 1900s. This pattern is evident in Idaho, where wolverines have been reported in 34 of 44 (77%) counties and presently occur in most, if not all, historically occupied habitat in Idaho. This resurgence is likely attributed to the important refugia provided by Idaho’s large wilderness areas and the wolverine’s status as a state-protected species since 1965. The wolverine is recognized as an Idaho Species of Greatest Conservation Need in the Idaho State Wildlife Action Plan based on low rangewide populations and lack of state population trend information.”[43]

The immediate and complete conflict of this research with the conclusions in the Proposal cannot be overstated. Similar more generalized sentiments were displayed by the State of Washington on the stability of the wolverine population in the Cascades, as Washington Fish and Game concluded in 2020 as follows:

“The occupancy estimate of 43% for the survey area in Washington indicates that nearly half of the suitable habitat available in Washington was used by wolverines during the survey. Given the substantial amount of suitable habitat in the Washington Cascades, this finding suggests that the wolverine population is sufficiently large and widely distributed to be unlikely to suffer extirpation in the immediate future. Give the limitations of our data, we cannot provide reliable projections for population persistence over longer time periods.”[44]

While Washington does not provide specific population numbers, this information would indicate their conclusions are an upward trend for populations in the State. Again, this is far from the collapse that the Service is asserting as occurred. Similar positive trends for wolverine populations were provided by the State of Wyoming which clearly stated their findings in 2020 as follows:

“The survey, planned to be repeated at five year intervals confirmed the broad distribution of wolverines across the region and documented population recovery above their historic lows. For the first time ever, wolverines were detected in the Gros Ventre Mountains and the southern Wind River Range.”[45]

Again, this is far from the collapse of populations of wolverine that the Service is asserting is occurring. In 2022 Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Department provided the following conclusion on populations of wolverine in Montana as follows:

“Wolverines were detected in the same number of cells during each study, although there was a slight shift in detections from Montana to Idaho. The significance of these spatial differences in detections will be discussed in the manuscript that is currently being drafted by Lukacs et al. Wolverines continue to be detected throughout the extent of their known range and have also been recently detected in areas previously thought to be outside of their normal distribution. ”[46]

This published peer reviewed position falls well short of the collapse in populations that the Service is asserting based on research entirely outside the DPS. The direct conflict of the Service conclusions with all state information regarding the wolverine causes us significant concern that the Proposal has only selectively applied new research. Research noted in conclusion is more than 15 years old making any assertion of new information for the listing impossible to defend. This is a problem that must be resolved if any assertion of new research being the basis for applying the 2013 listing is to be found factually accurate.

4(b) Factual uncertainty of wolverine with changes in Canada regulations.

The Organizations are aware that there are questions about the status of the wolverine populations in Canada generally. Canadian wolverine in the far north of Canada appears to be highly sustainable, despite the unregulated operation of dispersed motor vehicles and their unrestricted trapping. The Canadian government and Alberta provincial governments are both looking at revising regulations for wolverine trapping as over trapping appears to be the basis for decline. As the Organizations have noted throughout, we are very concerned that the entire Proposal is horribly predecisional. The Service has chosen to blindly move ahead with listing rather than waiting to see what the Canadian response is in terms of trapping regulations and the benefits of addressing the primary threat to the species. This simply makes no sense as US regulations will never solve a Canadian issue.

The challenge that is again presented by the predecisional making in the Proposal is the fact that if we accept the 2013 listing and its conclusion that southern 48 United States was a DPS based on the different regulatory processes and standards for the species, we must question if Canadian regulations are heightened is the 2013 conclusion on the DPW still even valid. Again, these are foundational questions that must be resolved.

The predecisional nature of the decision to not address Canadain government responses to wolverine population changes also allows managers to avoid other foundational questions. Another question that the decision to simply move the 2013 listing forward is the fact that the 2022 Barrueto research is addressing wolverine population in an area outside the area researched by Aubry in 2008. Again, we are unable to align these decisions and research efforts as they are not even addressing populations of wolverine in generally the same areas. This is simply nowhere near best available science but is simply an attempt to create a worst case scenario for the species to support the preordained decision of the listing, mainly that the species would be listed and motorized recreation was the primary threat.

5. Significant new research and management documentation have found that snow compaction is a natural process.

The relationship of dispersed winter recreation and wildlife has been the topic of some of the most theoretical and speculative analysis in the listing of species possible. Again, this is a theory that we continue to be told has never been researched, despite the fact it has been researched extensively. The failure of the Proposal to accurately reflect threats to the wolverine is further evidenced by additional research that has been published and concludes that snow compaction at the landscape level is a natural process. This research again found the presence or lack of snow as the single largest factor impacting wolverines based on three years of site-specific tracking of a large number of animals. [47] At no point are factors such as recreation or human activity even mentioned in this research. Even more troubling is this research is again not mentioned in the Proposal.

These conclusions are buttressed by the fact that 41% of wolverine habitat in the lower 48 is in Congressionally designated Wilderness or National Parks, where the large-scale use of what is asserted to be a primary threat simply does not occur. This research calls into direct question any assertion that human activity can possibly compact snow to such a level as to impact the species. This type of a concern has been woven throughout the discussion of possible concerns around human recreational activity in all forms compacting snow and providing a competitive advantage to other species.

The snow compaction concern has been present with wolverine questions since original proposals and research on the species started. This research coincided with concerns about lynx being possibly impacted by snow compaction, which was highlighted in the astonishingly speculative and theoretical 201Lynx Conservation Assessment and Strategy. In the decade following this document, sufficient research was performed to allow the 2013 LCAS for the southern Rockies to remove snow compaction as a threat to the lynx. The most recent update for the lynx has completely removed dispersed recreation and snow compaction as threats to the Lynx. The Organizations must question how two species that were at one point almost identical in research and management concerns could have taken such hugely different courses in management decisions over the same period of time. This Glass research is not addressed in the Proposal before it concludes that recreation is a threat despite researcher’s conclusions on compaction not even being addressed in either document.

6. The Organizations support the Proposal determination that critical habitat for wolverine cannot be determined.

While the Organizations have serious concerns with the basis of the Proposal, we do support the decision to not designate critical habitat for the species at this time. While the Organizations support this determination, we would be remiss if we did not recognize that the conflict between lacking information to designate critical habitat and asserting there is sufficient research to identify recreation as a primary threat is immense. The Proposal outlines the decision not to identify critical habitat as follows:

“Therefore, due to the current lack of data sufficient to perform required analyses, we conclude that the designation of critical habitat for the DPS is not determinable at this time in accordance with 50 CFR 424.12(a)(2)(i). The Act allows the Service an additional year to publish a critical habitat designation that is not determinable at the time of listing (16 U.S.C. 1533(b)(6)(C)(ii)).”[48]

The Organizations are intimately familiar with the significant economic impacts that could result to western communities as a result of critical habitat designations for the wolverine. We have specifically not addressed issues such as economic analysis and other information to be addressed in a critical habitat designation based on the specific identification that this designation was not happening. Public comment must be provided on this issue and designation of critical habitat without this public comment is entirely inappropriate.

While we support the decision that critical habitat cannot be designated at this time, we are concerned that numerous other factors must be addressed in the designation of critical habitat for any species. Given the huge amount of uncertainty around threats to the wolverine issues such as what is necessary for the survival of the species. The recent Weyerhaeuser Supreme Court decision provides a standard that would be problematic on this issue which is outlined as follows:

“Even if an area otherwise meets the statutory definition of unoccupied critical habitat because the Secretary finds the area essential for the conservation of the species, Section 4(a)(3)(A)(i) does not authorize the Secretary to designate the area as critical habitat unless it is also habitat for the species.”[49]

Given the high level of mobility that has been well documented by the species, the Organizations must question how habitat for the species could be identified. Additional determinations must made regarding if the best interests of the species was furthered by such designation under the ESA. This is clearly identified as follows: