BLM Grand Junction Field Office

ATTN: Palisade Plunge Trail

2815 H Road

Grand Junction, CO 81506

GMUG National Forest

Att: Scott Armentrout

2250 Highway 50

Delta, CO 81416

Dear Katie and Scott;

Please accept this correspondence as the comments of the above referenced Organizations opposing The Plunge Trails Project, hereinafter referred to as “the Proposal”. The Organizations must oppose this Proposal as it directly conflicts with national trail guidance from the US Forest Service, BLM, IMBA and Colorado Parks and Wildlife, all of which clearly identify that there is a critical need for maintenance considerations to be addressed in the development of ANY trail project. The Organizations submit that these types of landscape considerations only work if everyone is held to the same standards, and the Organizations are aware that initial adoption of these types of landscape concerns can be difficult especially when efforts are overly focused on a single trail. The Organizations are becoming very frustrated that we are being forced to raise national maintenance guidance on so many projects throughout the state, as recently exemplified by this Proposal, Mad Rabbit, Burn Canyon, West Magnolia, and Signal Peak Mtn. Bike proposals. The motorized community has been the single largest partner of land managers for decades but application of varying levels of implementation of national guidance by user group or project is not acceptable to the motorized community as we are now the target of unnecessary conflict for asking questions of how this project conforms to the national guidance on the issue.

Many of these concepts regarding trail maintenance were institutionalized with the motorized community through the development of the voluntary adopted OHV registration program decades ago. The Organizations vigorously assert that while we were the FIRST ones to institutionalize maintenance efforts for the greater good, we never signed up to be the ONLY ones working for the greater good of the trails community. This program and partners now provide 10 maintenance crews in the northern end of the Grand Valley, and we are aware that agency money is leveraged in these efforts. When unsustainable projects are developed, the agency match to these efforts it put at risk, which is unacceptable to us especially when the unsustainable project benefits only a small portion of the trails community.

Prior to addressing our specific concerns, a brief summary of each Organization is needed. The Colorado Off-Highway Vehicle Coalition (“COHVCO”) is a grassroots advocacy organization advocating for the approximately 200,000 registered OSV and OHV vehicle users in Colorado seeking to represent, assist, educate, and empower all OHV recreationists in the protection and promotion of off-highway motorized recreation throughout Colorado. COHVCO is an environmental organization that advocates and promotes the responsible use and conservation of our public lands and natural resources to preserve their aesthetic and recreational qualities for future generations.

The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to ensure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands. For purposes of these comments, TPA and COHVCO will be referred to as “the Organizations”.

1a. The Organizations collaborate on a wide range of issues throughout the State.

Prior to addressing the Organizations specific concerns around the Proposal, the Organizations believe it is important to explain our history and background working on tough recreational issues with a diverse range of interests and public land managers throughout the State. A list of a few of these examples includes:

-

SB17-100 passage – The Organizations spearheaded passage of this state Legislation that significantly reduced the liability for all clubs performing stewardship projects on public lands in Colorado. While this legislation protected all not for profit organizations, the only group that showed up to testify in support of these efforts was The Nature Conservancy;

-

CPW LEAN Event – This project was the result of almost one year of collaborative efforts from the Organizations and CPW, the State Treasurers Office and numerous other groups regarding how to achieve more timely integration of grants from the trails program and as a result of these efforts all grants are now available to applicants almost 1 year earlier than before the LEAN event, and while these efforts again benefitted all grant applicants there was not support or input from any other user group;

-

Tenderfoot Mountain Project on Dillon Ranger District – the multimillion dollar Tenderfoot Trail project was constructed to benefit a wide range of interests including motorized and mechanized users with improved wildlife habitat being the goal of the collaborative effort after years of abuse of the area by a wide range of interests;

-

Bear Creek Trails Project on the Pikes Peak Ranger District – the Bear Creek Trail was moved and rebuilt from scratch to address possible impacts to genetically pure cutthroat trout habitat in the area; this project was more than 4 years of effort and the major source of funding was the OHV grant program;

-

Hermosa Watershed Legislation outside Durango – This was a first of its kind federal legislation addressing landscape management standards resulting from years of collaborative interests ranging from water, ranching, local government, snowmobile, summer motorized and mechanized and the Wilderness Society that took almost a decade;

-

Badger Flats Campground project on South Park Ranger District – the Organizations collaborated with the Wilderness Society, campers, land managers, local property owners and other interests to renovate a poorly managed area into a regional trails hub and camping facility with an extensive multiple use trails network;

-

Bangs Canyon SMA outside Grand Junction – another collaborative spanning more than a decade on the GJFO where again a diverse range of interests collaborated to develop a multiple use area that also improved wildlife habitat and protected cultural resources for more than a decade;

-

667 Trails Project on Pikes Peak Ranger District – restoration of a heavily used trail network lost in the Hayman Fire and then heavily impacted by flooding that resulted from almost 20 years of effort;

-

Hartman Rocks area of Gunnison Field Office – a multiple use area where ongoing efforts longer than a decade and have leveraged OHV resources to develop a unique trails-based recreation area that has been highly successful;

-

Canadian Lynx management research with USFWS – a project CSA partnered with the USFWS to facilitate targeted lynx research by providing resources and expertise to researchers working to understand the relationship between lynx habitat and recreation. This support ranged from removing snowmobiles that are broken or stuck in the backcountry during blizzards with CSA grooming equipment to oil and gas for basic operation to educating researchers on how to ride and operate equipment in the backcountry.

The Organizations are proud of the history of collaborative projects that have developed across often wide interest groups with benefits for all parties involved. In these efforts, often laying the groundwork has been very slow and often verging on shaky but throughout these efforts a strong foundation was important in uniting groups and interests as the projects moved forward and resulted in quality projects being developed and being successful in the long run.

The Organizations would also note that even where other groups could have been excluded from benefits of collaborative efforts because of their failures to become involved in any manner in the discussions or efforts (Such as SB 17-100; CPW LEAN; Lynx Research etc.) these groups have not been excluded from the scope of benefits. It is unfortunate that collaborative effort has not been displayed in more projects in the State, such as the passage of the lodging tax in Steamboat and related implementations that has been the driving force in this discussion. The Organizations submit that if such an open and collaborative effort had been pursued much earlier in the process for the Plunge development, BLM staff would not have been in the situation we are now facing.

1b. OHV/OSV funding to the CPW Trails Program benefits all users.

In addition to the above collaborative projects, the Organizations have supported the development and implementation of the voluntary registration programs for both summer and winter motorized recreation that is coupled with a small amount of funding from the Federal Recreational Trails Program. Similar discussions of voluntary registration programs have simply been dead on arrival when discussed with other trail user groups. It is important to note that the small amount of funding available to non-motorized programs through RTP has overwhelmingly provided to the mtn. bike community over the years. The voluntary OHV funding provides almost $8 million annually(or $1.25 for every resident of the State) per years for trails of all kinds, and this funding has been provided by the motorized community for more than 20 years. This funding maintains routes for the benefit of all users, as all motorized trails are open to all other forms of recreation and is essential to providing basic access and maintenance.

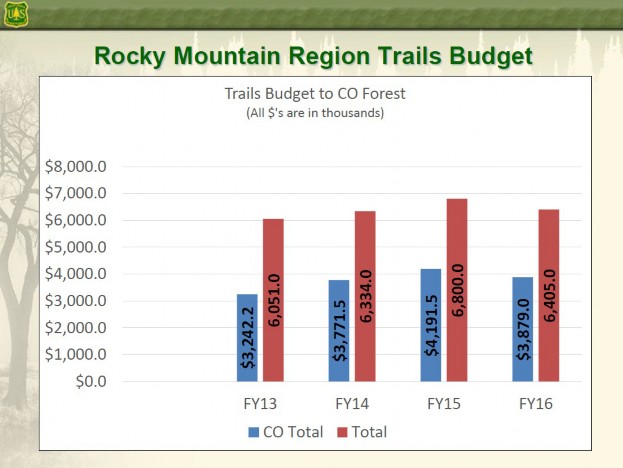

The lion’s share of this program funding is directed towards basic maintenance of existing facilities for a variety of reasons. The importance of just the $4.3 million in OHV funding to the entire recreation community is displayed in the following slide from the USFS presentation of Scott Haas at the 2015 OHV workshop:

The Organizations have attached the CPW summary of the 2018 OHV funding grants for your reference, and avoid any discussion around possible inaccuracy of our summary of the program. While we are aware that this graphic is based on USFS budgets and spending, the Organizations have to believe the relationship is similar in terms of funding for the BLM. Furthermore the $4.3 million in OHV funding is leveraged with an additional $1.1 million dollars for winter recreation route maintenance and almost $2.4 million in funding for maintenance for non-motorized recreation. In addition to providing a massive portion of the funding for basic recreational funding in the State, motorized community has also been repeatedly identified as the largest single source of volunteer support for trails in the State of Colorado in annual VOC reports.

While the State Trails Program is the largest funding source in the State, the Organizations can say with absolute certainty, that this Program simply does not go far enough in terms of maintenance even with the support of the motorized community. The limited scope of benefit for this funding results in the desire to leverage the OHV program funding with all outside funding to provide basic maintenance of facilities, which we have generally come to summarize as “The rising tide floats all boats”.

The Organizations are also intimately familiar with the limited benefit that can be achieved with any outside funding to the program, which gives significant concern for the Proposal, especially when the Proposal is based in an area where basic maintenance will be expensive due to the steep angles of the route, highly erodible soils and remote nature of the project. The Organizations must ask that if there is truly funding available to support projects like this from outside sources, why would this funding not be used to support all recreational interests?

1c. What the motorized community does for maintenance in the Northern portions of the Grand Valley.

As previously noted, the CPW trails program is a strong partner with land managers in providing basic maintenance of recreational opportunities for all at the landscape level. The value of this program to both USFS and BLM land managers in the Grand Valley is almost $2 million per year, and directly benefits all recreational users of public lands. These support projects include:

- 6 good management crews in the Northern Grand Valley region;

- GFJO GM Crew;

- DENCA GM Crew;

- Grand Valley GM crew;

- Statewide Heavy crew on an as needed basis;

- UFO GM Crew; and

- West slope ATV Maintenance Crew.

- 4 winter grooming maintenance crews in northern Grand Valley;

– Delta; Grand Junction, Rifle and Hotchkiss winter grooming programs that support hundreds of miles of groomed winter routes in the valley that are open to all free of charge; and - Extensive direct funding for projects on an as needed basis;

– this has provided motorcycles, rental of mini-excavators, rock breakers and trailers to leverage the efforts of maintenance crews and other volunteers.

The Organizations have embraced the maintenance needs of land managers and have been consistently informed that partnering in this manner is the single most effective manner to keep trails and opportunities open on public lands. The Organizations are aware that this partnership has resulted in multiple maintenance teams being available for most offices and are highly effective at leveraging agency resources. No other partner group comes close to this level of support. The difference that this funding has made to on the ground efforts is reflected in the fact that while most land managers have lost their trail maintenance crews in other parts of the country over the last 20 years, Colorado managers have expanded access to crews and equipment when compared to 20 years ago. Almost all of this funding and equipment has come from the voluntary registration program that embraced maintenance efforts more than a decade ago.

While the Organizations have provided a strong partnership with land managers for the benefit of all recreational users of public lands in Colorado, there is clearly a need for additional partner funding. The allocation of this partner funding is often concerning when projects are moved forward where there is not a mentality of the rising tide floating all boats or where large sums of money are used for the benefit of a small user group. This type of single minded proposal places undue stress on existing efforts to benefit all users, as for a rising tide type model to be successful, all users must be working towards the same goals. Additional stress is placed on these types of partner models when projects are moved forward and there is no model of maintenance for the project once it is completed. This is a double loss in the eyes of the Organizations as:

- Funding was allocated to the project originally and has been lost for maintenance; and

- Existing maintenance demand is expanded to keep unsustainable and expensive projects open and maintained, which draws maintenance money away from other efforts.

The Organizations must vigorously assert that when the rising tide model is not adopted for all projects, this puts the Organizations in the situation where new trails for multiple use are not being built while other groups are creating trails for the benefit of themselves. The situation where the motorized community would not be able to build trails, despite maintaining roads and trails used to access the area, while other users are allowed to build trails without addressing the basic maintenance of routes and trailheads used to access those trails is simply and foundationally unacceptable to the motorized community. This is where the partnership with land managers is needed, to encourage other users to help float the greater boat.

2a. The Plunge fails basic questions provided in national BLM/IMBA Guidance on trail construction.

The sustainability of any remote steep route, that is on highly erodible soils that sees high levels of visitation is a major hurdle for development of the route both in terms of basic planning and the need for ongoing maintenance. Even with the best designs, trails with these parameters simply need maintenance. The failure to recognize this in the EA for the Proposal is troubling. Rather than meaningfully addressing this issue, the EA simply asserts as follows:

“Long-term Maintenance

Long-term maintenance would be the responsibility of the respective land management agencies (BLM and Forest Service) and their partners (e.g., COPMOBA) and would include repair of erosion control features, culverts, and corridor clearing (brush and tree removal or trimming) as needed. The land managers and their partners would maintain the trail to meet the trail management objectives, specifications, and user experiences described above, and in the EA for the Palisade Rim Trail (DOI-BLM-CO- 130-2010-0047-EA). Short reroutes, within 20 ft of the original designated route, would be authorized if a natural event (e.g., flash flood, rock slide) substantially alters the usability of the route, and standard maintenance is not practical. The BLM and Forest Service would monitor the trail at least once annually and more frequently following intense high rainfall precipitation events to determine which areas require maintenance. The BLM and Forest Service would also use other landowner, user, and partner reported maintenance needs to help determine priority areas and timing for maintenance.”1

It has been the motorized community experience that many of these basic maintenance challenges are far more easily resolved with funding but there is no similar funding stream for other trail communities in Colorado even though many of these same challenges were highlighted in new guidance from the BLM on developing successful mountain bike projects. The identification of funding to address maintenance issues identified above are major challenges for any trail project and were a driving force for the motorized community to establish the OHV program in Colorado. We simply cannot understand how these costs are not more meaningfully addressed in the Proposal.

These types of basic maintenance challenges are consistently identified as major planning issues by all land managers, and the Organizations believe these national statements speak for themselves. The BLM national guidance created in partnership with advocates for the interests now seeking to develop the Proposal (IMBA) outlines these concerns as follows:

“Three components of trail sustainability

- Environmental sustainability – Will the Trail provide for resource protection?This is the definition that is commonly used when referring to what does or does not provide for a sustainable trail.

- Social sustainability- this is frequently overlooked in the trail development process. Evidence of the failure to meet desired user outcomes (experiences and associated benefits) are everywhere: Overcrowded trails; trails with little use; trail users who feel pushed out by other users and unauthorized routes

- Economic sustainability – Can the land managers and local community bear the long terms costs of maintaining a trail? If it provides a valuable experience, is it likely worth the investment, but this must be weighed against shrinking maintenance budgets” 2

The economic sustainability challenges are more extensively detailed in subsequent portions of these comments but the social and resource sustainability questions must not be overlooked as well. Social sustainability concerns are based on the fact that the project fails to address the rising tide floating all boats and resource sustainability will be a major issue given the steep terrain, highly erodible soil, remote nature of the project and high-speed nature of the trail. The direct and vigorous user conflict between ourselves and the mountain bike community that has resulted from the motorized community asking questions such as those posed in these comments is direct evidence of the negative social sustainability around the Proposal.

The environmental sustainability concerns simply will have to be addressed as the project moves forward , even if there is no funding for these issues and they have not been addressed in the EA. The critical need to identify the environmental concerns for the projects, and how they will be mitigated, is a major concern for the Proposal given that a significant portion of the trail is located in BLM management areas where the goals are for Wildlife Habitat. The site-specific challenges resulting from a project of this size in a remote area, on highly erodible soils with a large number user on an exceptionally steep slope are addressed in subsequent portions of these comments.

2b. The Plunge has major conflicts with USFS trail sustainability goals.

As the Organizations have noted above, significant volunteer efforts and direct funding of land manager efforts for decades has been directed towards the basic sustainability of the motorized portions of the trail network throughout the state of Colorado. Again, the Organizations must stress that every mile of route maintained is available to ALL types of usages. The need for expansion of this model of management and sustainability was highlighted in 2016 when the USFS issued the US Forest Service National Strategy for sustainable trails system, which expanded the model that has been so successful in Colorado as national programmatic goals and objects for trails management moving forward.

This strategy highlights the basic need to form maintenance and sustainability partnerships with the following reasoning as follows:

“Achieving a sustainable trail system presents several challenges. With limited funding, compounded by the rising cost of wildfire operations and the associated decrease of nearly 40 percent in nonfire personnel, the Forest Service faces a lack of capacity for managing trails on the ground and for building partnership synergies within the trails community.”3

The Sustainable Trail initiative continues on how the challenges faced by the Agency as a result of the declines in budgets as follows:

“A generation ago, nearly every ranger district had its own trail crew, but that is no longer the case. The Forest Service will overcome a significant reduction in field staff by moving from a model of “doing it all” to a model of shared stewardship in order to achieve mutual goals and receive shared benefits.”4

Colorado can vigorously stand as a complete variation from this norm, as every ranger district and field office has access to a crew and almost every ranger district and filed office has a dedicated motorized trails crew on the district as a result of the OHV program. There are six of dedicated summer crews on the Northern end of the Grand Valley planning area and another 4 winter crews. The Organizations must ask why other groups are not seeking to leverage these relationships and experiences?

The critical need for land managers to lead partners on the need for sustainable trails and recreational opportunities is also highlighted in the USFS Sustainable Trails efforts as follows:

“Sustainable Change: Leader-led change is often initiated with a high level of impact that may wane over time. Grassroots-led change often grows slowly, yet must be adopted by leadership to achieve lasting results. Sustainable change is cultivated where leader intent meets grassroots initiative and both are infused with regular feedback and support.”5

It is interesting to note that the high levels of impacts may result from USFS efforts to instill this type of grassroots model for recreation trails is specifically identified in the 2016 but for reasons these impacts have often been simply avoided, sparing applied and then avoided again after perceived impacts were expressed.

The USFS Sustainable trails initiative further highlights the seven core values of the partnerships as follows:

“Core Values

At the Forest Service, we are embracing seven core values and invite our partners, volunteers, and friends to join us in adopting these values to guide our collective efforts. By adopting the following core values, we lay the foundation together for making sustainable trail systems a priority and ensuring pathways to public lands remain—for all people, for many generations to come.

Safety—We value the safety of trail users, volunteers, partners, and employees and are dedicated to performing our work safely and providing safe trail opportunities for all.

Sustainability—We value the land and will steward a trail system that is relevant to a changing society, is ecologically viable, and that can be sustained by current and potential partner, volunteer, and agency resources.

Commitment—We value the strong traditions, skills, and dedication of our partner, volunteer, and employee workforce and will foster continued growth through training and leadership opportunities.

Access—We value the ability of everyone to connect to the outdoors and are committed to providing quality access through a variety of trail settings and opportunities.

Inclusion—We value everyone—trail users, partners, volunteers, employees, and friends, regardless of age, ability, or cultural background.

Communication—We value the exchange of information that is up-to-date, accurate, widely available in multiple formats, and relevant to both trail users and those involved in sustainable trail planning, design, and maintenance.

Relationships—We value collaborative relationships and are committed to working across jurisdictional and cultural boundaries to maximize diverse skillsets and generate innovative approaches.”6

With the passage of the National Trail System Stewardship Act in 2016, Congress memorialized many of the goals and objectives of the USFS Sustainable Trails Strategy into law.7 As a result, not only is some of the foundationaldecision-makingtroubling the Organizationsaround the Proposal, it is a violation of the USFS Strategy and now could be a violation of federal law.

While the Organizations have strived to achieve these common values and goals of the National Policy well before the National Policy was formalized, many other groups have not been as proactive. The Organizations must question why the National Policy has not been raised in these planning efforts by the district. That has highly frustrated the Organizations as we are now being forced to address these National Goals and Objectives of the Agency alone.

2c. The Plunge conflicts with the 2017 CPW Trails Master Plan.

The Organizations must that CPW has developed a Statewide Master Plan for Trails, and the Proposal also conflicts with the requirements of this plan as well. The CPW statewide plan provides as follows:

“4. Emphasize responsible stewardship for all phases of trail development and use.

4.1 Accentuate the importance of natural resources conservation, including wildlife and habitat, in conjunction with trail recreation, in the design, construction, maintenance, and enjoyment of trails.

4.2 Prioritize trails development and maintenance that is sustainable and sensitive to the environment, while complementing other land uses (e.g., people can use trails to commute to work or school as well as recreation).”8

The high level of consistency across these three planning agencies and documents should not be overlooked or minimized regarding the need for maintenance and sustainability for any opportunities. Despite this the Proposal simply transfers monitoring and most managing expenses to the land managers, but this type of allocation is exactly the type of decision making that national guidance from all relevant land managers have clearly and directly identified as a major planning goal.

2d. Basic sustainability of any trail project is a major challenge.

As noted above the motorized community has institutionalized funding of basic maintenance in partnership with land managers throughout the state and as a result is now able to identify the rock star trail maintenance crews and those projects and areas where basic maintenance needs are not being met. From this location, a systemic failure to understand the basic needs of the trails community regarding the ongoing maintenance needs from certain user groups has resulted in the collapse of some trail networks in the state already. Mainly this has resulted from situations where users have pledged to support trail expansions, managers are then subjected to intense public pressure to build the trail network and then users are unable to provide basic maintenance, seasonal closure resources and educational materials as pledged.

A few examples of these collapses are exemplified by the following projects:

- Shavano to Gateway Project – City of Montrose is now being brought in to manage an area previously expanded and maintained by users after there was a complete failure of seasonal closures and basic maintenance;

- Several trail expansion projects in the Grand Valley area where a failure of maintenance in the area was identified in the recently released RMP but users continue to push for expansions of routes after local communities have pledged maintenance resources;

- Steamboat City Park System maintenance- Another situation where an expanded trail network has been developed and then users are failing to maintain that system;

- Vail Valley Expansion- This project outside Avon Colorado was the result of systemic failures to enforce seasonal closures and for mtn. bikers to stay on designated routes.

The challenges faced by partner driven projects for land managers has also been highlighted in numerous articles in local papers. BLM managers addressed the Oil Well Flats area outside Colorado Springs as follows:

“the success of the Oil Well Flats is a proud sight for Leonard, who personally designed the network and lead the coalition of volunteers, cycling enthusiasts and trail groups that built it…..though some of the areas admirers might find it hard to swallow, adding miles to Oil Well Flats would pose an undue strain on the area, which has no toilets and can only support so much dispersed camping….. It is a situation that has become familiar at the climbing areas along Shelf Road to the North. There the BLM has struggled to keep up with demand for campsites, toilets and access trails….. BLM is working on addressing the growing pains at the Oil Well Flats, including the top concern: Managing human waste.”9

These challenges are not limited to the Oil Well Flats area as the Durango Herald recently published a detailed article about the challenges that are facing land managers in the Durango area from illegal trail building, failures of users to obey use restrictions and impacts from the lack of partner maintenance. A copy of this article is included with these comments. While these types of articles have become common place in Colorado and these are issues where the Organizations have partnered effectively to address these challenges for multiple use areas, the Organizations submit this model of successful trail projects must be applied to all projects regardless of the types of usage. Ignoring these problems will not make them go away but it will reduce the amount of funding that can be leveraged for the benefit of all users of public lands.

In addition to the direct request for funding to the State Trails Program, other indications are often noted and concerning around the long-term sustainability of any trail program. These would include numerous requests for maintenance grants from various land managers to third parties, and the CPW trails program has been the recipient of an alarmingly large number of these after the fact types of grants the last several years. what has become a systemic issue mainly that grant applications identifies the critical shortfall that already exists on routes outside those maintained by the motorized crews. Often some of the largest management and maintenance challenges that are presented are unrelated to a project, such as recreational shooting, trash removal and basic upkeep of facilities such as toilets. These are issues that also must be addressed in the Plunge as it is significant to note that CPW was not able to fund any of these after the fact grants in the last several cycles as non-motorized money is super competitive, often has high match amounts and is not matched with any voluntary user type registration monies.

These types of systemic problems are a major concern for the Plunge as several of the partners in developing the Proposal have already pledged to maintain thousands of miles of trails in the Grand Valley. The results of these pledges on the ground have been mixed as partners are basing the ability to maintain on positions that simply lack factual basis. Thousands of miles of trails cannot be maintained with a few volunteers and hand tools and is concretely exemplified by the fact the average good management crew can only maintain 100-200 miles of routes a year. The Organizations are aware that many of these partners have made extensive commitments across numerous land management agencies and offices in the Grand Valley and often land managers are unable to determine a total commitment from the that partner because of these land management boundaries and agencies. The Organizations would ask that before any project moves forward that any partner in the maintenance of the project be thoroughly vetted to fully address commitments made already, resources that have been identified, the previous successes or failures of that partner and clearly identifying new resources that will be provided for the new route. The Organizations would note that these types of concerns from land managers are exactly why the OHV grant program developed in the manner it did.

Given the Organizations decades of involvement in the State Trails program, the Organizations are aware of the level of resources and dedicated staff that is necessary to maintain this mileage of routes. Full time employees, such as the good management crews, that are well equipped is a bare minimum and access to heavier mechanized equipment is a critical component of a successful maintenance program. Plunge development partners simply don’t have access to these types of resources and any assertion that the levels of maintenance can be done with hand tools and volunteers on the weekend simply lacks any factual basis. When projects are developed but not maintained, land manager resources are removed from partnerships where the rising tide is floating all boats and are reallocated to try and avoid failure of poorly developed projects and this negatively impacts all recreational access in the planning area and further more results in negative environmental impacts to the area. These type of impacts are a major black eye for all trails users.

2e. Funding to even construct the Plunge is weak.

The Organizations are aware that the Proposal is one of the Governor’s 16 in 16 or Colorado the Beautiful Proposals. When the 16 was developed there was a pledge of $10 million raised from partners to develop these projects. This partner funding has resulted in less than $2 million for construction. This is not a major hurdle to be overlooked for mere construction of the route but this results in larger issues for the long-term maintenance of the route. Where does this leave maintenance? On the shoulders of the land managers is the answer.

Unfortunately, this is not the only time when pledged partner funding for projects simply failed to materialize. When the Tenderfoot project on Dillon Ranger District was in initial stages, significant portions of funding was alleged to be available from unspecified sources from the non-motorized interests. This funding simply never developed at levels close to the assertions and the motorized program and land managers bore the lions share of costs to remediate a multiple use area. Similar experiences have also occurred on the Bear Creek project on the Pikes Peak Ranger District. Large amounts of user passion are simply not a replacement for an identifiable funding source for development and maintenance of projects. Projects simply cannot move forward with unsubstantiated assertions of abilities of partners. Projects must be based on a demonstrated ability of a partner to continue to maintain what they have and the new network that is being asked for. Often partners cannot maintain what they have.

3a. The Plunge is a huge project and will need constant maintenance.

Whatever the Plunge project looks like when completed, it will need significantbasic maintenance for the foreseeable future due to the steep terrain, erodible soils, levels of usage and remote location of the route. Insuring that is funded by the users supporting that project is critical to insuring that limited land manager funds are not directed away from the current maintenance backlog to address new trails used by a small portion of the trails community. There will need to be trees cut off trails, facilities maintained, trash removed, users educated about route locations and the need to stay on the trail, seasonal gates installed and used that will remain ongoing. Compounding these challenges is the fact that other easier routes currently exist in the planning area that will continue to need maintenance and upkeep even after the Plunge is opened.

Generally, the social sustainability of the Plunge is a serious question given the small target audience that will be using the Plunge. This is simply not a route that can be used by the average bicycle rider as most will not seek out a one way only trail of more than 30 miles in length. Even for those that seek out the opportunity, most simply will not be able to traverse the highly technical 30-mile route and will seek to end their ride well before the end of the trail. This is an issue as there are no bailouts for riders who want to exit early in the Proposal, and as a result unauthorized trails will explode as people simply seek to end their recreational experience on the Plunge. Any assertion of value to any other user groups simply lacks factual basis given the high-speed nature of gravity biking that will be occurring on the Plunge. People simply will not hike on this trail.

The economic sustainability of the Plunge is also a major concern as under most planning guidelines for trails, the Plunge simply would not be constructed. The Proposal is simply too steep, soils are too erodible and the distance covered is simply too long. Even providing basic maintenance for the route will be a major challenge as equipment will have to travel over long distances on steep and rocky loose terrain to perform basic maintenance. You simply cannot get mechanized equipment over the step terrain and even transporting a chainsaw to cut trees will be difficult. Given the steep nature of the Plunge, maintenance of even a properly designed trail will have to occur on a weekly basis. In this section of our comments, we desire to provide concrete examples of the lack of social and economic sustainability around the project. This is by no means exhaustive but it rather intended to clearly establish the basis for our concerns on the Proposal.

With regard to economic sustainability, throughout out the Proposal, administrative and operational costs are simply overlooked or transferred to land managers without discussion. The EA simply provides as follows:

“Long-term Maintenance

Long-term maintenance would be the responsibility of the respective land management agencies (BLM and Forest Service) and their partners (e.g., COPMOBA) and would include repair of erosion control features, culverts, and corridor clearing (brush and tree removal or trimming) as needed. The land managers and their partners would maintain the trail to meet the trail management objectives, specifications, and user experiences described above, and in the EA for the Palisade Rim Trail (DOI-BLM-CO-130-2010-0047- EA)…. The BLM and Forest Service would monitor the trail at least once annually and more frequently following intense high rainfall precipitation events to determine which areas require maintenance.”10

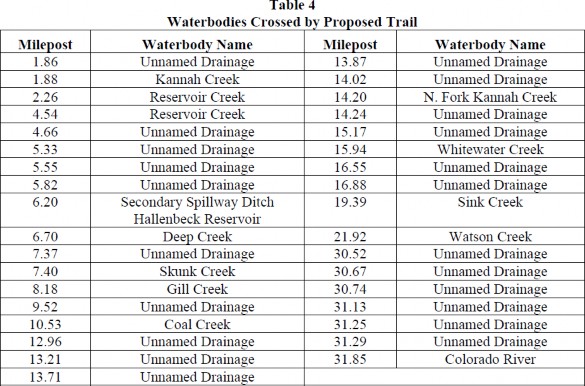

The draft EA for the Proposal clearly identifies the route will cross no less than 18 waterbodies 11, which are identified as follows:

As previously noted, the Proposal asserts that the primary maintainer and monitor of these 18 water crossings would be the land managers. These are the kind of basic maintenance and monitoring that the motorized community has worked hard to assist in addressing. It is unacceptable that other users would now be allowed to transfer this type of basic maintenance cost to land managers without clearly identifying how it will be paid for. This is not a rising tide floating all boats.

Unfortunately, water crossings are not the only time that specific management costs are never addressed or badly underestimated, such as the 14 different locations that signage will be necessary. The Proposal asserts that signage will simply be provided on an as needed basis for the Proposal as follows:

“The BLM and Forest Service may place trail markers at 1-mile intervals if monitoring indicates that this is necessary. Possible locations for long-term signage, gates, and kiosks, and limiters are:”12

The expectations of this signage are aggressive to say the least as the EA states:

“Long-term signage would be installed to help users have a better trail experience, to provide for safety on the trail, and to provide educational information. The signs would include trail name signs and maps within the trail system and trailhead signs at trailheads and/or major intersection points. The frequency of trail markers would be based upon monitoring of trail users.”13

Clearly the EA is expecting something significantly more than carsonites with stickers for designations, which has been the norm on public lands for decades. These may not be the prettiest signs but they are cost effective and easily replaced. Developing and maintaining signage such as that expected in the Proposal is hugely expensive compared to carsonites. Signage is an issue the OHV community is intimately familiar with as we are aware that even carsonites are expensive and often have a short lifespan and need to be replaced, especially in the early stages of a project, or when closing social routes. Signage is again basic operational costs that the motorized community has born for decades outside the good management programs through the OHV program at levels approaching $100,000 per year. It is simply unfair to move these types of costs over to land managers. Some type of identified funding source for these signs must be identified and clearly incorporated in the EA. Simply expecting it to happen is unrealistic and exactly the type of maintenance costs that national guidance seeks to have clearly identified.

Social trails are another issue where costs of management are simply never addressed. This will be a major concern as many users who start the Plunge trail will probably be overwhelmed quickly by the high-altitude nature of the trail and high levels of expertise needed. Rather than seeking to finish the 30-mile one-way trail, these riders will look for a way out of the trail, regardless of the designation of the route. These escape routes will be problematic given the fact that significant portions of the Plunge are in Hookless Cactus and designated wildlife habitat areas. Rather than addressing the ongoing nature of this challenge, the EA asserts this mitigation will only be occurring on the front end of the project. Hookless cactus issues are of serious concern to the motorized community as a result of the fact that anytime there is litigation on any ESA plant issues, all trails are immediately challenged and land managers are often forced to close all routes until the litigation is resolved. This was recently again highlighted in the PSI litigation against the USFS by defenders of Wildlife and others. In addition to reducing partner funding, motorized trails would be put at risk direct risk of loss if this management fails.

The Organizations believe a brief discussion regarding the hazard tree situation on the district highlights the need for an expansion of basic maintenance efforts with partners. The following pictures represent daily situations where trees have fallen across designated routes and have fallen in a location that creates a basic safety concern for the public. Situations like this must be resolved in a timely manner to avoid safety concerns for trails users and insure that the public does not reroute the trail footprint to continue use of these routes.

It has been the Organizations experience that this is the type of basic maintenance that can only be effectively done with a dedicated crew in a timely manner, despite a large number of these issues being simply addressed by the public when encountered. Often these issues are simply removed by a maintenance crew that is using the trail to get to a larger worksite. While probably entirely unnecessary to state, these maintenance issues are entirely unrelated to the trail design and layout as trees are going to fall for decades no matter how the trails are laid out.

While informal partner groups might be able to address smaller hazard tree related issues, as a result of the poor forest health on the district trails and routes are now being subjected to major blowdown events that involve hundreds of trees over an extended length of trail. In the picture below, the designated route runs directly through the center of the blowdown.

The Organizations are intimately aware that resolving blowdown situations such as those above can take a professional crew utilizing modern equipment weeks to resolve. Any assertion that an informal maintenance program can deal with challenges of this scale simply lacks factual basis and should not be overlooked in a rush of public interest to build trails. The Organizations submit that failure to address the growing scale of maintenance needs will result in limited land manager resources being drawn away from existing maintenance crew efforts that we know are still not going far enough on existing trails.

3b. Education of users at the landscape level will be an important component of the Proposal.

The Organizations are also aware that there are extensive wildlife concerns around the plunge Proposal, which have been compounded by the recent significant expansions of trails in the in the Grand Valley for the benefit of the mountain bike community. This is another issue that the Organizations are very concerned about as once an area is at capacity in terms of wildlife habitat, it has been our experience that no new trails or other facilities are allowed. Developing an understanding of what that capacity across this area really looks like will be a significant issue moving forward for species such as elk and deer. These are issues that simply are not addressed in the Proposal. This is another area where meaningfully addressing maintenance and education of users regarding seasonal closures and other management tools will be critical to the success of any trail expansions. The motorized community is concerned about the success of any trail expansion, as has been shown on the PSI, litigation will pull all trails users into the matter, regardless of if the specific trails are involving that group or not.

In what has become an interesting issue, the basic need for a stay the trail or tread lightly type ethic program for all users of public lands in addition to the maintenance and monitoring previously addressed has become very apparent as research indicates that:

“Outdoor recreation has the potential to disturb wildlife, resulting in energetic costs, impacts to animals’ behavior and fitness, and avoidance of otherwise suitable habitat. Mountain biking is emerging as a popular form of outdoor recreation, yet virtually nothing is known about whether wildlife responds differently to mountain biking vs. more traditional forms of recreation, such as hiking….Few studies have examined how recreationists perceive their effects on wildlife, although this has implications for their behavior on public lands…..Approximately 50% of recreationists felt that recreation was not having a negative effect on wildlife. In general, survey respondents perceived that it was acceptable to approach wildlife more closely than our empirical data indicated wildlife would allow. Recreationists also tended to blame other user groups for stress to wildlife rather than holding themselves responsible.”9

This situation was very interesting to the motorized community as everyone has blamed motorized usage for decades for every issue on public lands. Here we have a situation where motorized impacts are irrelevant but the need for many of the same guidance and educational materials is equally as important to the success of the project as they have been for motorized usage and there are no provisions made for these types of materials.

3c. Seasonal closures are completely unrealistic.

Another example of the complete lack of basis for the Proposal involves the winter closures, which will need to actually be enforced as the Plunge is immediately adjacent to a wildlife concentration area and is habitat for numerous amphibians. It has been the Organizations experience that any areas where amphibians are present is to be seasonally closed during the breeding season to avoid contact between recreational usage and the toads. It has also been our experience that when populations decline motorized is blamed despite the fact that they may not be the issue. Despite these concrete concerns for seasonal closures the EA merely states:

“Winter Closure

Winter closure (December 1 through May 1) for mountain biking would be in effect from MP 11.6 on NFS lands to the eastern boundary of and through the BLM Rapid Creek Wildlife Emphasis Area ending at the intersection with the southern Palisade Rim Connector trail near MP 30.4. The BLM would use adaptive management to provide flexibility for the location of the western extent of the big game winter closure (e.g., specific dates may be adjusted annually based on weather conditions and coordination with CPW). Mountain bike riders would be allowed to use the trail from the intersection near MP 30.4 to eastern boundary of the Rapid Creek Wildlife Emphasis Area near MP 27.48 as long as BLM monitoring indicates that trail cyclists are not continuing to the south past MP 27.48 during the winter closure period.

If BLM monitoring indicates that any cyclists are riding to the south past MP 27.48, then the BLM would enforce the closure point at the trail intersection near MP 30.4. The BLM would consider moving the closure location as far west as MP 30.4 if there are any violations of the winter closure point at MP 27.48. Big game winter range closures may also include pedestrian travel (e.g., hikers and runners) if the BLM determines that this additional use restriction is necessary to reduce disruption to big game during the winter season. The BLM may adjust seasonal limitation periods annually based on coordination with CPW (e.g., mild winters, late hunting seasons, etc.). Proper gates and signage would be installed to ensure adherence to the winter closure. Trail segments on other portions of NFS lands would “self close” in the winter due to winter conditions.”14

The number of assertions that are made in that winter closure standard is astonishing and directly evidences the complete lack of understanding of how to implement a winter closure. Variable dates of closure are impossible to educate any user group regarding and clear dates are the only way to address trail access for summer recreation. Without the prohibition of the hard dates, people will assume the route is open. When people have traveled to the top of the trail, they are going to use it. Seasonal closures are most effective when they are consistent so users can travel to other locations to recreate and can be provided to users before they reach the trailhead.

The Organizations would also note that the assumption that BLM will monitor the area is immediately made along with the assumption of installation of gates and BLM will be available to open and close these gates on an as needed basis. Again these are costs and management issues that are not addressed and should be in order to develop a successful project and avoid impacts to existing funding and not putting other users routes at risk when management of the issue fails. These are the basic management challenges that resulted in the good management program being created by the motorized community and have been the downfall of many of the non-motorized trail projects in the state previously addressed.

4. Economics contributions from the Proposal are simply unrealistic.

The Organizations are also concerned that one of the major benefits to local communities and economies is tragically overestimated and simply never even addressed in the EA. This overestimate is concerning as there are clearly expansive costs for the development and maintenance of the project that are not meaningfully addressed. According to supporters of the Proposal the Proposal would result in an estimated $5 million a year in spending for the planning area.15 No basis for the estimation is provided, so unfortunately this is an issue the Organizations are forced to address with general information on the issue.

In 2014, Mountain bike researchers concluded that those using backcountry mountain bike trails in the Squamish areas outside Whistler BC ski areas spent $37 for visitor per day.16 These conclusions are reasonably consistent with both USFS and BLM conclusions regarding the spending of the mtn. bike community utilizing backcountry opportunities. In order to generate $5 million annually the Plunge would need to generate more than 136,000 plus visitor days or more per year. That would be more than 11,000 visitors per day on average for the 7-month period the Plunge is expected to be open. Such a high level of visitation is again basis for questions about basic maintenance of the Trail.

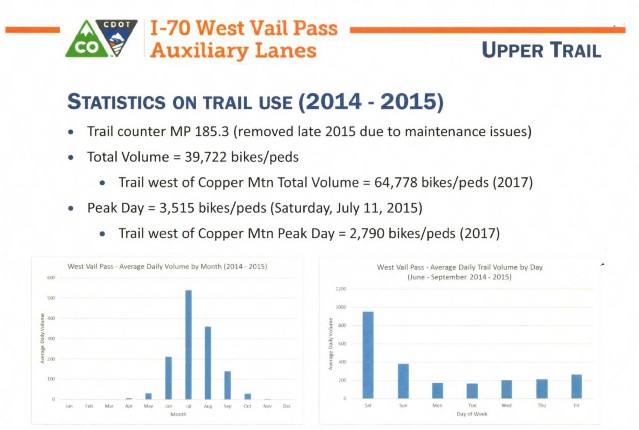

There is simply no basis in fact or reality for such levels of visitation to the Plunge and rather much easier trails in the area are simply not seeing anywhere near this level of visitation. The Organizations have been actively involved in discussions around possible impacts to the Vail Pass National Recreation Trail from lane expansions on I70 between mile markers 180 and 190 in Summit and Eagle Counties. The Vail Pass National recreation trail sees high levels of visitation to the area, both from the general public and permittees due to the proximity to I70, as the trail weaves in, under and around I70 in this area. This is an easily accessible paved trail that is nationally recognized. Despite this ease of access and broad appeal, USFS estimates visitation at levels of only 1/3 of the visitation that is projected for the Plunge.

While the economic contribution of the Vail Pass National Recreation, trail was not estimated in the I70 project, the USFS was able to provide detailed information on visitation, which is as follows:

Given the disparity or Proposal estimates when compared to detailed high-quality information from other sources, the Organizations must seriously question the accuracy of the information used to calculate these benefits. These types of failures are even more concerning given the systemic failure to address basic operational costs of the Project.

Conclusion.

The Organizations must oppose this project as it directly conflicts with national trail guidance from the US Forest Service, BLM, IMBA and Colorado Parks and Wildlife, all of which clearly identify that there is a critical need for maintenance considerations to be addressed in the development of ANY trail project. The Organizations submit that these types of landscape considerations only work if everyone is held to the same standards, and the Organizations are aware that initial adoption of these types of landscape concerns can be difficult especially when efforts are overly focused on a single trail. The Organizations are becoming very frustrated that we are being forced to raise national maintenance guidance on so many projects throughout the state, as recently exemplified by this Proposal, Mad Rabbit, Burn Canyon, West Magnolia, and Signal Peak Mtn. Bike proposals. The motorized community has been the single largest partner of land managers for decades but application of varying levels of implementation of national guidance by user group or project is not acceptable to the motorized community as we are now the target of unnecessary conflict for asking questions of how this project conforms to the national guidance on the issue.

Many of these concepts regarding trail maintenance were institutionalized with the motorized community through the development of the voluntary adopted OHV registration program decades ago. The Organizations vigorously assert that while we were the FIRST ones to institutionalize maintenance efforts for the greater good, we never signed up to be the ONLY ones working for the greater good of the trails community. This program and partners now provide 10 maintenance crews in the northern end of the Grand Valley, and we are aware that agency money is leveraged in these efforts. When unsustainable projects are developed, the agency match to these efforts it put at risk, which is unacceptable to us especially when the unsustainable project benefits only a small portion of the trails community.

Please feel free to contact Scott Jones, Esq. if you should wish to discuss any of the issues that have been raised in these comments further. His contact information is Scott Jones, Esq., 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont Colorado 80504; phone 518-281-5810; email Scott.jones46@yahoo.com

Respectfully Submitted,

Scott Jones, Esq.

COHVCO/TPA Authorized Representative

Don Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

Enclosures

1 See, DOI BLM Preliminary Environmental Assessment for the Palisade Plunge Trail; March 2018 at pg. 24.

2See, DOI Bureau of Land Management and IMBA; Guidelines for a Quality Trail Experience; Mountain Bike Trail Guidelines; January 2017 at pg. 4.

3See, USDA Forest Service; National Strategy for A Sustainable Trail System; December 30, 2016 at pg. 3. Hereinafter referred to as “USFS strategy”.

4 See, USFS Strategy at pg. 3.

5 See, USFS Strategy at pg. 4.

6 See, USFS Strategy at pg. 5.

7 See, PUBLIC LAW 114–245—NOV. 28, 2016.

8 See, CPW; 2016-2026 Statewide Strategic Trails Plan; 2017 @ page 3.

9 A complete copy of this article is enclosed with these comments for your reference.

10 See, DOI – BLM; Preliminary Environmental Assessment for the Pallisade Plunge Trail; March 2018 @ pg. 25.

11 See, DOI – BLM; Preliminary Environmental Assessment for the Pallisade Plunge Trail; March 2018 @ pg. 15.

14 See, DOI BLM Preliminary Environmental Assessment for the Palisade Plunge Trail; March 2018 at pg. 25.

15 See, https://eplanning.blm.gov/epl-front- office/projects/nepa/80546/137873/169617/Palisade_Plunge_Preliminary_EA_News_Release.pdf

16 A complete version of this research is available here – https://www.mbta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Squamish-EI-Report-April-3-2017.pdf