Cal Joyner, Regional Forester

333 Broadway Blvd. SE

Albuquerque, NM 87102

Re: Magdalena RD Travel Management Proposal Protest

Dear Mr. Joyner:

Please accept this correspondence of the protest/appeal of the Trail Preservation Alliance with regard to the Magdalena Travel Plan (“the Proposal”). Prior to addressing the specific concerns on the Proposal, TPA believes a brief summary of the Organization is necessary. The Trail Preservation Alliance (“TPA”) is a 100 percent volunteer organization whose intention is to be a viable partner, working with the United States Forest Service (USFS) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to preserve the sport of trail riding. The TPA acts as an advocate of the sport and takes the necessary action to insure that the USFS and BLM allocate to trail riding a fair and equitable percentage of access to public lands.

Executive Summary.

TPA has participated in a huge number of Ranger District level travel management plans and is very concerned regarding the limited analysis provided in the Proposal’s EA. It has been TPA experience that an EIS is the standard level of analysis relied on for district level plans in order to insure a legally sufficient analysis of issues is provided on what is always a difficult and contentious issue for the USFS to address. This is again proven true on the Magdalena as the overwhelming basis for public comment on the draft was the closure of routes. While the vast amount of public comment was related to limiting closures of routes, the Proposal failed to address many basic flaws in the draft EA on the underlying research, such as failing to fully explore current management, failing to provide a full range of alternatives on contested issues and failing to meaningfully address economic impacts from the Proposal.

TPA submits that given this overwhelming public input seeking to maintain current levels of multiple use access to the area, which is consistent with credible input from a wide range of partners, there is clearly unresolved conflicts about alternative uses of available resources. This conflict mandates a full, complete and meaningful review of these issues as a matter of law under NEPA.

TPA submits that two alternatives are available that satisfy the purpose and need of the proposal and do not close 40% of the routes in the planning area. The first alternative that is available and never addressed is simply recognizing the existing routes in the area and placing them on an MVUM. As the purpose and need is clearly identified as the need for the Magdalena RD to comply with the Travel Management Rule, this alternative has frequently been used by the USFS to achieve this goal. TPA submits that many ranger districts facing budget issues frequently identify existing routes in the district on their MVUM and simply do not close any routes. This decision has been frequently litigated and the USFS has been highly successful in defending these decisions. The second alternative that was simply never addressed would be the determination that existing roads could be designated as trails and allowed to remain open for access to recreational opportunities, as the Mount Taylor Ranger District of the Cibola NF recently determined was a viable means to achieve the goals and objectives of the Proposal. TPA would note that the purpose and need of the Mount Taylor project and the Proposal are almost exactly the same, and as a result this management clearly represents an alternative that was not explored. TPA submits this comparison is highly relevant as the Mount Taylor Ranger District is immediately adjacent to the Magdalena District in the Cibola NF. Why the alteration of roads to the lower trail level of classification was not explored remains unresolved and entirely unclear in the final EA and related documents. TPA vigorously submits that the analysis provided to date artificially limits the scope of alternatives provided in violation of NEPA.

Agency determinations regarding the need for closures of approximately 40% of the routes in the planning area are never analyzed or reviewed and fall well outside alternatives which could fulfill the purpose and need of the project. TPA submits there are clearly two management options to comply with the TMR, additional analysis must be provided to address the need to close an additional 40% of routes in the planning area as is the preferred alternative of the Proposal. After an extensive review of the EA, this analysis simply cannot be located as no reasons for closures, such as resource impacts, Endangered Species concerns or limited USFS budgets are even mentioned.

TPA submits that development of all alternatives for usage of current resources simply has not occurred and has compounded failures to meaningfully address the economic impacts to local communities from the Proposal. Rather than meaningfully preparing an EA, the complete lack of information on economic impacts from altered recreational usage is noted and the EA simply moves forward. TPA submits this falls well short of the hard look at issues required by NEPA.

The only non-recreational economic activity that is identified in the Proposal as possibly being impacted by the Proposal is firewood gathering. This position simply lacks any factual basis as USFS documentation identifies that firewood gathering is 17th on the list of reasons people visit the planning area. TPA vigorously asserts that motorized access plays a critical role in the other 16 activities higher on the list of reasons people visit the area, and no reason is given for why possible impacts to these 16 other activities are not addressed.

Each of these issues is a per se violation of NEPA requirements and mandate the Proposal be overturned and returned to the district in order for an accurate economic analysis to be performed and all alternatives be explored.

2a. The sufficiency of the scope of an EA is subject to a DeNovo standard of review as this is a question of law.

TPA submits that there are three issues to be reviewed in this appeal. Two of these issues are subject to a “de Novo” standard of review, mainly economic analysis determinations and the compliance with federal planning requirements, and one issue is subject to an review under the arbitrary and capricious standard. TPA submits that a detailed statement of high quality information simply has not been provided to justify the closure of approximately 40% of routes on the Magdalena RD, when the purpose and need of the project can be achieved by simply adopting existing routes and publishing their MVUM. TPA further submits that admitting there is no user information to allow for review of the economic impacts of alternatives is a violation of the NEPA requirements that all alternatives be given a hard look at in order to address unresolved conflicts regarding usage of existing resources .

TPA commends the Ranger District is attempting to streamline the NEPA review process as mandated by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act1 and TPA does not contest that an EA analysis is not required to comply with high levels of detail provided in an EIS. TPA vigorously asserts that at no point is an EA level of analysis allowed to move forward when there are critical gaps in data being relied on and a full range of alternatives has not been provided as directly evidenced by the complete lack of a baseline alternative for many issues.

CEQ regulations address the sufficiency of EA level analysis of the range of alternatives and impacts under an Environmental Assessment as follows:

“Environmental assessment: …. (b) Shall include brief discussions of the need for the proposal, of alternatives as required by section 102(2)(E), of the environmental impacts of the proposed action and alternatives, and a listing of agencies and persons consulted.2

§102(2)(E) of NEPA specifically states the scope of review for contested issues under an EA is as follows:

“(E) study, develop, and describe appropriate alternatives to recommended courses of action in any proposal which involves unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources;”3

Relevant Court rulings applying section 102(2)(E) have specifically stated:

“This Court . . . has not construed section 102(2)(E) narrowly to apply only to agency actions that propose an identifiable use of a limited resource like park land or fresh water. Instead, we have ruled that federal agencies have a duty under NEPA to study alternatives to any actions that have an impact on the environment, even if the impact is not significant enough to require a full-scale EIS.” 4

TPA submits that there are clearly unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources and that the current road and trail network in the planning area represents an available resource. These types of projects are exactly the type of federal actions where the impacts to the human environment were to be fully analyzed. The sufficiency of the conflict resolution is subject to the heightened De Novo standard of review as a result of the critical importance to comply with this basic legal mandate.

TPA submits that the unresolved conflict regarding existing road and trail resources involves the determination by the Ranger District that none of the roads and trails could be subjected to lower levels of management and maintenance, Such limited management would continue to allow the high quality recreational opportunities to be provided and minimize any negative economic impacts to local communities that could result from loss of these opportunities. The nature of this conflict was directly evidenced by the fact that access to the Magdalena RD was the single largest issue that arose in the public comment process and that the Mount Taylor Ranger District pursued exactly this plan in their recent Travel Management Plan, which had an identical purpose and need as the Proposal.

The issue of limited access to public lands has also been identified as an ongoing conflict regarding existing resources in a wide range of documents from the USFS, it planning partners such as the Western Governors Association and the New Mexico Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan(“SCORP”) and reports from various federal agencies. TPA submits that the decision to move forward with the Proposal without addressing the lack of economic analysis and an illegally narrow scope of alternatives that did not address conflict regarding access to existing routes was done at the peril of the planners. The complete lack of a baseline alternative for many facets of the EA was the basis of a wide range of comment from an exceptionally diverse range of users during the comment period. The decision to move forward with the insufficient baseline of analysis and range of alternatives has resulted in an EA that suffers from many flaws and facial violations of NEPA which can only be addressed by returning the EA to the district for additional analysis and alternatives may be developed to comply with NEPA requirements.

2b. The standard of review for economic analysis is a de novo standard as the Courts have consistently substituted their judgment regarding the accuracy of economic analysis.

Courts have consistently held agencies to a much tighter level of review of economic analysis when compared to other issues within the agency expertise in the NEPA process as the court makes their own conclusions regarding the accuracy of review without deference to agency findings. Relevant court rulings addressing economic analysis in NEPA have concluded:

“an EIS serves two functions. First, it ensures that agencies take a hard look at the environmental effects of proposed projects. Second, it ensures that relevant information regarding proposed projects is available to members of the public so that they may play a role in the decision making process. Robertson, 490 U.S. at 349, 109 S.Ct. at 1845. For an EIS to serve these functions, it is essential that the EIS not be based on misleading economic assumptions.” 5

The Court then discussed the significance of economic analysis in planning as follows:

“Misleading economic assumptions can defeat the first function of an EIS by impairing the agency’s consideration of the adverse environmental effects of a proposed project. See, South La. Envtl. Council, Inc. v. Sand, 629 F.2d 1005, 1011-12 (5th Cir.1980). NEPA requires agencies to balance a project’s economic benefits against its adverse environmental effects. Calvert Cliffs’ Coordinating Comm. v. United States Atomic Energy Comm’n, 449 F.2d 1109, 1113 (D.C.Cir.1971). The use of inflated economic benefits in this balancing process may result in approval of a project that otherwise would not have been approved because of its adverse environmental effects. Similarly, misleading economic assumptions can also defeat the second function of an EIS by skewing the public’s evaluation of a project.” 6

The level of accuracy of the hard look at economic analysis applied by the Court in the Hughes River decision is significant as the Hughes River Court invalidated an EIS based on an error in economic contribution calculations of approximately 32%. 7 TPA submits that creation of the comparison between current usage and usage after implementation of the EA simply is not possible directly evidencing a violation of the Hughes River decision. No baseline of visitation to the area is provided to attempt to apply economic analysis of recreational usage that is commonly available. In the Proposal, economic analysis simply identified the insufficiency of information as follows:

“Insufficient information exists to accurately estimate changes in recreation use that would occur under implementation of the action alternatives analyzed in this report.” 8

Given this statement, TPA submits that the economic analysis of the EA is facially insufficient and the determination that there will be no impacts to recreational spending as a result of the proposal simply lacks any factual basis. TPA submits that this failure to provide even basic information is a per se violation of NEPA as there is a large range of user spending profiles and a wide range of recreational activities relying on the network of routes in the planning area to achieve their recreational objectives. These issues were raised in the comment period from a wide range of users and the EA never attempts to resolve this issue but rather dismisses recreational impacts and only identifies all other activities that might be impacted as firewood gathering. This position is a per se violation of NEPA and the Hughes River decision.

2c. The mandated hard look of NEPA at issues simply has not occurred in the Proposal.

TPA believe a brief summary of the arbitrary and capricious standard of review that are applied by Courts reviewing the hard look of an agency in NEPA analysis is relevant to this appeal/protest, as the courts have consistently directly applied the NEPA regulations to EIS review. As a general review standard, Courts have applied an arbitrary and capricious standard of review for agency actions within their expertise under NEPA. This standard is reflected as follows:

“…it required only that the agency take a “hard look” at the environmental consequences before taking a major action. See, Kleppe v. Sierra Club, 427 U. S. 390,427 U. S. 410, n. 21 (1976). The role of the courts is simply to ensure that the agency has adequately considered and disclosed the environmental impact of its actions, and that its decision is not arbitrary or capricious. See generally, Citizens to Preserve Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe, 401 U. S. 402, 401 U. S. 415-417 (1971).” 9

The CEQ regulations note that a detailed statement of high quality information is a significant tool to be relied upon in the public comment process required for all NEPA actions. These regulations clearly state this relationship as:

“NEPA procedures must ensure that environmental information is available to public officials and citizens before decisions are made and before actions are taken. The information must be of high quality. Accurate scientific analysis, expert agency comments, and public scrutiny are essential to implementing NEPA.” 10

TPA vigorously asserts that while the majority of the issues raised in this appeal are subject to the heightened scrutiny of a de Novo review, much of this analysis is so deficient as to fail to satisfy the hard look standard. The fact that the EA recognizes that there is no data regarding recreational visitation to the planning area directly undermines any assertion of a hard look at possible impacts and utilization of existing resources. TPA submits that a hard look at issues is more than recognizing a lack of data and making no effort to resolve the lack of information.

3a. The EA fails to review basic alternatives that achieve the purpose and need of the Proposal.

TPA must express significant concern that the Proposal determines that a detailed analysis “no action alternative” is not necessary. While the TPA agrees that the no action alternative of an EA may be somewhat more limited than an EIS, the TPA is simply unaware of any authority that provides for a basic failure to address current management under an EA. TPA vigorously asserts that undertaking a district level travel plan and only preparing an EA is highly unusual to start with. The determination to prepare an EA with numerous faults that are recognized during the original comment period but never resolved directly evidences the failure to comply with NEPA regulations. The overwhelming number of Ranger Districts doing similar projects chose to fully review all issues and prepare an EIS. TPA vigorously asserts that choosing only to prepare an EA has allowed alternatives to be overlooked and faulty analysis to be provided to the public as the review was only an EA.

TPA believes that a review of relevant standards for an EIS range of alternatives is highly relevant to the preparation of an EA as an EA is allowed to undertake a slightly lower level of analysis when compared to an EIS. At no point is there any authority that allows an EA to simply skip issues on the basis that the agency has not compiled the necessary information. As noted by numerous experts, the rational decision-making process of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is compromised when agencies consider only a limited range of alternatives to their proposed projects.11 When reviewing ranges of alternatives provided in a NEPA analysis, the courts have consistently held:

“The alternative section is ‘the heart of the environmental impact statement,’ 40 C.F.R. 1502.14; hence, ‘[t]he existence of a viable but unexamined alternative renders an environmental impact statement inadequate.” 12

When determining if an EIS has provided a satisfactory range of alternatives, the standard of comparison is to the purpose of the rulemaking and EIS. The courts have consistently held:

“[E]nsure that federal agencies have sufficiently detailed information to decide whether to proceed with an action in light of potential environmental consequences, and [to] provide the public with information on the environmental impact of a proposed action and encourage public participation in the development of that information.” 13

While an EA has a slightly reduced mandatory level of analysis when compared to an EIS, at no point in NEPA is there any authority that allows planners to recognize faults in analysis and move on. When the CEQ regulations and relevant federal laws for preparation of an EA are consolidated to a single standard, the conflict of the limited scope of the Proposal is immediately apparent. The combined single standard would be as follows:

Environmental assessment: …. (b) Shall include brief discussions of the need for the proposal and study, develop, and describe appropriate alternatives to recommended courses of action in any proposal which involves unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources of the environmental impacts of the proposed action and alternatives, and a listing of agencies and persons consulted.

As previously noted, a no action alternative must be provided when there is “unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources.”14 NEPA also finds that a full range of alternatives must be provided when there is conflict regarding the usage of existing resources. TPA submits that there can be no factual argument that the existing road and trail network is an existing resource and there is conflict over the future of these resources and as more extensively discussed in subsequent portions of this document, there are numerous alternatives for developing an MVUM that are available that are simply never mentioned and certainly not analyzed.

3b. Alternatives to the Proposal are clearly available that simply have never been addressed.

TPA must vigorously object to the artificially limited scope of the Proposal in terms of alternatives that have been provided to the public for at best weak comparisons of impacts. Two alternatives are frequently utilized by the USFS to achieve the objective of creating an MVUM but for reasons that are not clear simply The limited range of alternatives and failure to address the no action alternative was the basis of a large number of public comments during the comment period. Many USFS Ranger Districts have simply moved all existing routes onto the MVUM in order to comply with the travel management rule, and then moved to a designated routes system on the district MVUM after sufficient information has been collected to allow for a full and complete review of impacts from any closures. TPA submits that this process is so common that a citation to a particular plan is totally unnecessary. Clearly this represents an alternative to the Proposal which was not explored as the no action alternative simply is never meaningfully developed in the Proposal.

TPA submits that the recently finalized Mount Taylor Ranger District Travel Plan provides an example of another alternative for developing a travel management plan for the ranger district. The Mount Taylor District chose embrace the recreational usage of the district and to make large scale movements of existing roads to a variety of width of trails in order to maintain access. This decision is HIGHLY relevant to the Magdalena RD process given the geographic proximity of the two districts and the similarity in the timing of these processes. TPA also submits that the viability of this proposal as an alternative to the proposal is directly evidenced by the fact that the purpose and need of each of these plans is functionally identical. The purpose and need of the travel management plan on Mount Taylor Ranger District is as follows:

“Purpose and Need – There is a need to comply with 36 CFR 212.51(a), which requires the forest to designate motor vehicle use on National Forest System roads, trails, and areas by vehicle class, and if appropriate, by time of year. There is also a need to comply with the Travel Management Rule, 36 CFR 261.13, which requires that forests prohibit motor vehicle use off the system of designated roads, trails, and areas, and motor vehicle use that is not in accordance with the designations.” 15

The purpose and need of the Magdalena RD travel plan is as follows:

“Purpose of and Need for Action – There is a need for improving the management of motorized vehicle use on National Forest System lands within the Magdalena Ranger District of the Cibola National Forest and National Grasslands in accordance with the provisions of the Travel Management Rule at 36 CFR parts 212, 251, and 261. The Travel Management Rule requires the district to provide for a system of NFS roads, NFS trails, and areas on NFS lands designated for motor vehicle use. There is a need to comply with the Travel Management Rule, 36 CFR 261.13, which prohibits motor vehicle use off the designated roads, trails, and outside designated areas. There is a need to amend the Forest Plan to be compliant with the Travel Management Rule (see Appendix A).” 16

TPA submits that the purpose and need of these two planning processes is functionally identical and as a result of the geographic proximity and similarity of timing of these processes the Mount Taylor proposal clearly represents an alternative for management of the Magdalena RD routes that was simply never addressed for reasons that are not clear. TPA submits that any assertion to the contrary would lack factual and legal basis and that there are clearly two alternatives available to the Magdalena RD to develop an MVUM without the proposed closures. At no point is there any analysis of why these alternatives were found to be unacceptable.

3c. The failure to accurately address economics in the planning process will lead to significant management issues with the implementation of the Proposal.

The failure to address the no action alternative and a full range of alternatives compounds facial failures in economic analysis of the Proposal. Concerns regarding the critical role that economic analysis plays in NEPA have been raised by a wide range of highly credible third parties and were again the basis of extensive concern in the public comment process. Rather than address the critical nature that tourism and recreation play to the New Mexico economy, the Proposal provides following information on impacts to recreational usage that might result from the Proposal:

“Insufficient information exists to accurately estimate changes in recreation use that would occur under implementation of the action alternatives analyzed in this report.” 17

TPA is completely unable to identify any statutory basis or case law that allows NEPA to proceed at the Ranger District level and simply state there is a lack of information and move on. All case law and regulations require all impacts to the human environment to be meaningfully analyzed, not just those where information is easily available. Understanding the recreational visitation to the planning area is a critical component to developing a full and accurate review of the economic impacts to local communities that would result from the Proposal. It is beyond argument that recreational tourism has consistently identified as a critical component to these communities basic existence.

TPA is very concerned that the faulty economic analysis prepared in the Proposal have led to an allocation of resources in a manner that simply does not reflect user demands and will rapidly become unsustainable when the Proposal is implemented. TPA is not alone in their concerns regarding impacts of management decisions based on inaccurate economic analysis. The Western Governors’ Association released its Get Out West report in conjunction with its economic impact study of recreation on public lands in the Western United States which specifically identified that proper valuation is a significant management concern as follows:

“Several managers stated that one of the biggest challenges they face is “the undervaluation of outdoor recreation” relative to other land uses.” 18

The Get Out West report from the Western Governors’ Association also highlighted how critical proper valuation of recreation is to the development of good management plans based on multiple use principals. The Get Out West report specifically found:

“Good planning not only results in better recreation opportunities, it also helps address and avoid major management challenges – such as limited funding, changing recreation types, user conflicts, and degradation of the assets. Managers with the most successfully managed recreation assets emphasized that they planned early and often. They assessed their opportunities and constraints, prioritized their assets, and defined visions.” 19

TPA concerns regarding the Proposal and those expressed in the Western Governor’s Get Out West report virtually mirror each other. This concern must be addressed in order to avoid increases to many other management issues that were sought to be minimized with the creation of the Proposal. There can simply be no factual argument made that recreation has not been significantly undervalued as directly evidenced by the fact that no user or visitation information was obtained as part of the creation of the Proposal and that the only other usage of the planning area is firewood gathering.

4a. There is a wide range of credible research from the USFS that generally identifies a dispersed trail network as vital to small communities.

TPA is deeply concerned with the lack of consistency of the Proposal both in terms of recreational analysis and understanding the wide range of recreational activity that is dependent on the roads and trails for access with research that has been performed by other Federal agencies, State agencies and user groups regarding the specific levels of recreational spending and employment in the New Mexico area. TPA must note that the only other activity that is identified as possibly being impacted by the Proposal is firewood gathering. This position simply makes no sense as firewood gathering is identified as the 14th highest level of activity for the Cibola NF by the USFS. Many of the other more important usages of the existing road and trail network are simply never addressed as possible impacts from implementing the Proposal.

TPA is also deeply concerned that the limitations on access provided in all alternatives of the Proposal are inconsistent with more general statements regarding the economic importance of recreational access to rural communities from many of these same agencies and partners. TPA does not contest that site specific information may not be available for the planning area but TPA vigorously asserts there is a wide range of information on the issue available, none of which supports the basic direction of the Proposal. TPA believes that the fact that the Proposal is directly conflicting with information from these sources is an entirely different issue for NEPA analysis than asserting there is a complete lack of information.

The Forest Service has clearly identified the economic benefits that can accrue to a local community as the result of a multiple use trail network as follows:

“RECREATION AND TOURISM ARE VITAL TO MOST RURAL COMMUNITIES: This is true for virtually all rural communities but especially important to counties with high percentages of public land. Actions by public agencies to reduce or limit access to recreation on public lands have a direct impact on the local economy. Limiting access by closing roads, campgrounds, RV parking, and trails impact the surrounding communities. Visitors to public lands utilize nearby communities for food, lodging and support facilities. Interests include hiking, photography, horseback riding, biking, climbing, backpacking, birding, hunting, sport fishing, and many more. Public land agencies’ communication with community businesses is essential to job creation and stable rural communities.” 20

The Proposal also conflicts with a wide range of local planning efforts, such as the Catron County strategic plan which identifies the following as a management priority:

“a. Purpose The primary purpose of this Comprehensive Plan is to: • Maintain existing economic structures of mining, timber, ranching, and recreation while seeking new opportunities that are not in conflict with the existing economic structure.” 21

Clearly the basic direction of the Proposal and the fact that no change is noted in the economic contributions from recreation on the planning area despite loss of almost 40% of the access to the area conflicts with these statements from Catron County and the USFS. In addition to conflicting with landscape level analysis from the USFS regarding multiple use access to public lands, the Proposal conflicts with management priorities that are identified in numerous local planning documents.

4b. More specific analysis from the USFS identifies the huge role of recreational activity to the Cibola NF and the critical role understanding this usage plays in economic analysis.

Throughout the Proposal, isolated references are made varying types of usages existing on the Ranger District. TPA submits that these statements directly evidence the lack of factual basis relied on in the development of the Proposal and that insufficient information was available to address alternatives available and possible impacts from each alternative. The Proposal provides the following summary of overall uses in its recreation and scenic resources report:

“Recreation use on the Magdalena Ranger District is growing, partly because of the overflow of recreationists from the Albuquerque metropolitan area. Recreation use on the Magdalena Ranger District is primarily overnight use with the main users being hunters, campers, backpackers and rock climbers. The Day Use activities on the District include hunting, biking, pleasure driving, horseback riding, gathering forest products, rock climbing, and short day hikes. Hunting is a popular recreation activity throughout the district.”22

TPA is concerned that no basis is provided for this breakdown of usages and that at best only a limited attempt is made to reconcile impacts to these activities with the proposed changes in management. The basis for these assertions entirely lacks consistency with positions taken at other times that insufficient information is available to allow for meaningful economic analysis of the Proposal. This type of conflict in a detailed statement of high quality information is a direct violation of NEPA.

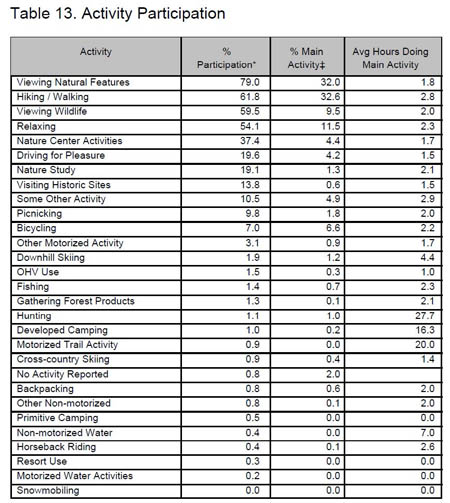

TPA would note that many of the activities identified in the Proposal as alternative uses of these areas are identified as some of the smallest primary uses of the planning area in relevant USFS NVUM research for the Cibola NF. TPA asserts that the large scale conflict between NVUM research and the limited and often conflicting information in the Proposal directly indicates the hard look of NEPA has not been complied with. The USFS NVUM research for the Cibola NF indicates recreational visitation as follows:

23

The complete lack of factual basis in the assertion of only two jobs being related to motorized usage of the planning area is further brought into question when the activities on the Cibola are reviewed. TPA does not contest that hiking ranks highly on the NVUM analysis, TPA is aware that motorized access is a huge factor in how the public utilizes hiking opportunities. While driving for please is 5th on that list, the motor vehicle is a primary method the public uses to view natural features and wildlife, hike, relax from daily stress and access their favorite hiking trailhead on the planning area. Each of these activities is a top five usage on the Cibola NF and the Proposal identifies that visitation to the planning area is primarily from the Albuquerque area. Clearly people are not walking from Albuquerque area to access these opportunities. The fact that every activity is directly related to motorized access and the Proposal asserts that only 2 jobs are related to this access is the type of conflict that directly evidences something other than the hard look of NEPA being relied on.

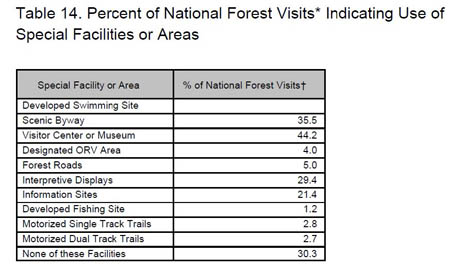

In addition to the above general summary of activities occurring on the Cibola, the NVUM research specifically identifies the primary facilities and developed sites that are used by the public when they are visiting the Cibola NF. This information is provided as follows:

24

Again these usage profiles do not support the position that only 2 jobs are related motorized access as the top 5 sites being visited are directly related to motorized usage.

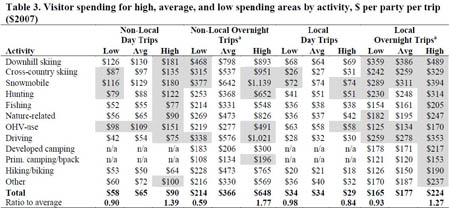

As part of the NVUM process, the USFS has also developed specific spending profiles for a wide range of recreational activities. This research provides the following information for planners to rely on in the development of local travel plans:

25

TPA submits that nationally the USFS recognizes a range of spending for an individual user on recreational activities from $20 per day to more than $1,000 per day. This wide range of spending should create a basic relationship between certain users and spending and that accurately measuring recreational visitation to a planning area is a critical component of developing meaningful economic analysis of any planning effort. A small change in a high spending user group would be difficult to offset with replaced visitation by users on the lower end of the spending spectrum. TPA submits that the economic impacts of the wide diversity in recreational spending is simply never addressed in the Proposal, which notes:

“Insufficient information exists to accurately estimate changes in recreation use that would occur under implementation of the action alternatives analyzed in this report.”26

The Proposal asserts that the following summary accurately reflects economic contributions of recreation as follows:

“Alternative 1. Proposed Action Employment and Income: Approximately 55 jobs and $1,454,773 in labor are supported by recreation. Two of these jobs and $37,015 in labor income are due to motorized uses.” 27

How these conclusions regarding recreational spending and possible impacts from the range of alternatives are reached in light of the admitted insufficiency of information is never explained in the EA. This is simply a violation of NEPA and leads to more questions on economic impacts from recreation than it ever could resolve. These questions include that any assertion that only two jobs in the Proposal area are related to motorized usage completely lacks factual basis as each of the top 5 usages of developed facilities is related to motorized access to the area. Any proposition that access a visitor center or interpretive site is only achieved via foot access simply lacks factual or logical basis, especially given the remote nature of the planning area and large visitation from the Albuquerque area. Motorized access is a critical component of these experiences. TPA is vigorously opposed to the fact that the estimate of economic impacts simply never changes for any of the alternatives and that based on these levels of spending in the EA, it is functionally impossible to achieve spending levels anywhere near 6 billion dollars spent on recreation and tourism at the state level that has been identified by a wide range of highly credible sources.

Predominately, the only secondary usage consistently identified in the EA as possibly being negatively impacted by the preferred alternative of Proposal is firewood gathering. On a 1.6 million acre forest this simply lacks any factual basis and directly conflicts with the visitor data that is available in the USFS National Visitor Use Monitoring research for the Cibola NF. Firewood gathering is 16th on list. In addition to the lack of credibility in such a position, this position directly contradicts the usages found by the USFS as part of their NVUM process. Given the facial conflict between these analysis, TPA must question the basic accuracy of any economic impacts from even the limited number of alternatives that are provided. TPA further submits that this conflict explains why there was no attempt made to summarize the no action alternative. The necessary information simply was never obtained, forcing TPA to question the decision to move forward with the Proposal without addressing this foundational issue. Such a decision is arbitrary and capricious and fails to meet NEPA requirements regarding accurate economic analysis.

4c. The New Mexico SCORP identifies the huge economic contributions to the state from recreation and the critical role that roads and trails play in delivering this experience.

While the Proposal failed to develop a meaningful baseline for economic analysis of impacts from management changes in the alternatives, TPA believes that establishing an accurate baseline for comparison of outside analysis to the Proposal is critical both to developing a quality plan and satisfying the hard look of NEPA. This type of landscape comparison also provides a meaningful reality check on the conclusions that are reached in local planning efforts. When expanded to the state level, local economic contributions should roughly correlate to state level conclusions. TPA submits that this correlation cannot be made when economic analysis in the Proposal is compared to state level analysis.

In addition to failing to provide any analysis of possible recreational impacts both in terms of quality of recreational opportunities and economic impacts to local communities, the only other usage identified as possibly impacted is firewood gathering. This simply makes no sense and again fails to address the fact that a multiple use route network is a huge component of providing a high quality recreational activities to almost every user of public lands in the Country. People simply are not hiking to the Magdalena RD in order to hike on the District.

The Outdoor Industry Association and Western Governors Association have combined to publish an extensive review the economic importance of recreation on public lands throughout the Western Unites States. This research concluded that outdoor recreation in New Mexico is a $6.1 Billion Dollar a year industry and results in 68,000 jobs in the State 28. Tourism has been identified as the largest or second largest economic driver in the State of New Mexico for literally decades. 27.3% of NM residents directly participate in OHV related activities.29 Third party research directly states that the dispersed road and trail network provides access for a wide range of activities.

The State of New Mexico has an extensive Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (“SCORP”) as required by the Land and Water Conservation Fund program. This document provides a wide range of information on the importance of recreation to the state’s economy and the critical role that trails provides in this experience. The SCORP clearly states the economic contributions of what has always been a critical component of the New Mexico economy as follows:

Economic Impact of State Parks and Outdoor Recreation

- Visitors to the New Mexico State Parks have been steadily increasing since 2005.

- Forty percent of New Mexico’s state residents participate in wildlife.associated recreation, both inside and outside New Mexico.

- Outdoor recreation supports 47,000 jobs across New Mexico and generates:

- $184 million in annual New Mexico state tax revenue.

- $3.8 billion in annually to New Mexico’s economy.

- $184 million in annual New Mexico state tax revenue.

- The outdoor recreation industry:

- Produces $2.75 billion annually in retail sales and services across New Mexico – accounting for 4.6% of gross state product.

- Provides sustainable growth in rural communities.

Except for those with direct economic interests, people often fail to consider the importance that outdoor recreation holds for local economies. In parts of New Mexico, outdoor recreation and tourism have long played an important economic development role. Many of New Mexico’s smaller and more rural communities are “gateway communities” that are located near an access point to an outdoor recreation site such as the national forest, a reservoir, ski area or historic site and usually derive a good measure of their community income from supporting outdoor recreation activities through lodger’s taxes, gross receipts taxes, and employment in businesses that sell supplies or provide hospitality services.” 30

As directly evidenced by the scope of these comments, there is a wide range of highly credible economic information available that could have been relied on to analyze the impacts to recreational usage and general tourism that would have resulted from the range of alternatives in the Proposal. TPA agrees that there is insufficient information to support the Proposal, but that does not mean there is no information. As directly evidenced by this Protest, the information simply does not support the Proposal. It does not mean that this information may simply be overlooked.

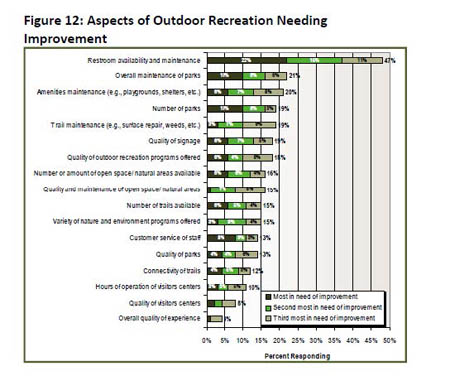

The New Mexico Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan further identifies that a lack of trails and low levels of trail maintenance and lack of associated facilities like bathrooms is a major concern for many residents in New Mexico. The SCORP clearly states:

TPA vigorously asserts that these findings are equally applicable throughout the state of New Mexico lands and would submit that there is no criteria identified in the SCORP that supports the basic direction and intent of the Proposal. Again, TPA would submit that the fact that research does not support the Proposal is very different than the complete lack of research that is asserted to exist in the Proposal. The conflict of the Proposal and existing research directly evidences the arbitrary and capricious nature of the Proposal and its failure to comply with NEPA requirements regarding both the range of alternatives and basic analysis of economic impacts that is required.

4c. The desirability of recreational hunting will significantly decline under the Proposal.

TPA has many members who are actively licensed hunters or fisherman and utilize a wide range of areas in these pursuits and fully utilize OHVs as part of their hunting experience, and often these visitors to the planning area are overlooked by groups allegedly advocating for hunting interests. Throughout the Proposal there are general allegations made that management changes are being undertaken to improve hunting opportunities in the Proposal areas. Recently, the National Shooting Sports Foundation in partnership with the USFWS and 20 different state wildlife agencies performed a national review of the issues that are impacting the hunting community and declining hunter participation rates in the US and what agencies can do to maintain hunter involvement in the wildlife management process. The NSSF research specifically concluded:

“Difficulty with access to lands for hunting has become not just a point of frustration, but a very real barrier to recruiting and retaining sportsmen. Indeed, access is the most important factor associated with hunting participation that is not a time-related or demographic factor—in other words, the most important factor over which agencies and organizations can have an important influence….” 31

The importance of hunting usage and access for funding of wildlife management activities, a significant issue that is directly related to hunting usage is overwhelming. This funding impact is summarized as follows:

“Hunters are avid conservationists who donate more money to wildlife conservation, per capita, than do non-hunters or the general population as a whole in the United States (Responsive Management/NSSF, 2008a). Hunting license fees and the excise taxes paid on sporting goods and ammunition fund state fish and wildlife agency activities and provide Federal Aid monies…. In fact, sportsmen, as a collective group, remain the single most important funding source for wildlife conservation efforts. Consequently, decreased interest and participation in hunting activities may have the unintended effect of reduced funding for important wildlife and habitat conservation efforts.” 32

The importance of motorized access to the retention of hunters is immediately evident when the means of access for hunting activity are identified.Hunters overwhelmingly use motorized tools for accessing hunting areas as cars and trucks are used by 70% of hunters, and ATVs are used by 16% of hunters. By comparison, only 50% of hunters identified walking as their access method of choice.33 The significance of closures on public lands is also specifically identified in this research, which identified that 56% of hunters specifically cited restrictions on motorized access and 54% identified closures of public lands by government agencies as significant issues for hunters.34

The funding streams secondarily impacted by hunters and suitability decisions are specifically of concern as hunting participation has been declining significantly over the recent few years and removing factors that were contributing to the declining participation was the basis of the entire NSSF report. This report specifically concluded that a lack of access to hunting opportunity was the largest addressable issue for land managers to address and improve hunter retention. Significant closures to multiple use routes in the Proposal area in the manner proposed will not improve access for hunters, and will over the long term reduce funding available for wildlife management. Reducing access to areas which are suitable for multiple use will only compound the changes and impacts to these secondary management issues. The conflict between this report and the EA basic direction are simply never addressed and again directly evidence the insufficiency of the EA in addressing both the range of alternatives and economic impacts of the proposal.

5b. Merit of a “close it and they will come” standard in economic analysis of recreational changes from Proposal.

Given the complete lack of analysis of visitation to the Proposal area or possible economic impacts from changes to the recreational opportunities on the Proposal area, TPA must address the possibility that closures to access were seen as an economic driver as part of the Proposal. This would be based on an assumption that there was a large number of users who were seeking a non-motorized experience with a high degree of solitude. It has not been TPA experience that closures result in increased visitation to areas, rather closures result in decreased visitation to areas even by groups that are seeking a dispersed recreational opportunity with a high degree of solitude.

For purposes of this document, this recreational experience will be referred to as wilderness, although TPA is aware there is only a small amount of Congressionally designated Wilderness in the Proposal area and those areas are outside the scope of the Proposal. While motorized recreation is the user group most directly impacted by a wilderness designation or management attempt, many other user groups such as the timber industry, hunters, fisherman and camping users are directly impacted as the most common means of accessing these areas for other forms of recreation are prohibited as well. Compounding the risks of negative economic impacts from the Proposal, Forest Service research indicates the total size of the wilderness hiker user group is rapidly getting smaller.35 This situation must be taken into account when addressing economic impacts of the Proposal, as the Forest Service has found:

“Trends in backcountry and wilderness use indicated rapid growth in the 1950’s and 1960’s, often exceeding 10 percent annual increases. Growth slowed in the late 1960’s and 1970’s to 3 to 5 percent average annual increases. Indeed, by 1976, overnight stays in national park wilderness and backcountry had peaked, and 1986 use was only 62 percent of that highest use year.” 36

In addition to the overall trend in usage declining, the Forest Service has found that other user groups which would be the target market for wilderness areas do not utilize the opportunities in wilderness type settings. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Research Station has found:

“Fishing (where possible), photography, nature study, and swimming (particularly in the Southeast and California) follow hiking as the most common activities in wilderness. Hunting is prevalent in some areas, but is always less than what might be expected. Even in such hunting hot spots as the Bob Marshall and the Great Bear wildernesses, just over 30 percent and 40 percent, respectively, of the sampled visitors hunted. Even in the fall hunting season, most visitors are not hunters.In a study of activity trends in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, hiking, fishing, and photography remained important across 1970 and 1982 users (Lucas 1985). Of these, only fishing declined, and that only slightly. Hunting was the only activity with a substantial change, and it dropped sharply in percent of total visitation.” 37

The Research Station’s study also addressed recreational usage trends for wilderness and clearly concluded:

“First, the need for additional wilderness allocation on the basis of recreational use demand is dropping. Use has stabilized or dropped in recent years. Population demographics suggest that use may decline even further….. Second, the benefits of wilderness recreation use accrue primarily to individuals in the region immediately surrounding the wilderness, People do not travel far to wilderness.” 38

Given these trends in wilderness area usage, TPA must object to any attempts to classify a wilderness type management standard as an economic benefit. Targeting any forest management proposal at a user group that is rapidly diminishing in comparison to total user numbers and that does not utilize existing opportunities makes little sense and would be a policy destined to fail. Maintaining access for user group that spends, on average, twice as much as the user groups and is steady or growing as a segment makes sound economic sense. Attempting to create positive economic impacts with any other type of planning simply makes little sense and would not be a good utilization of resources.

7. Conclusion

TPA has participated in a huge number of Ranger District level travel management plans and is very concerned regarding the limited analysis provided in the Proposal’s EA. It has been TPA experience that an EIS is the standard level of analysis relied on for district level plans in order to insure a legally sufficient analysis of issues is provided on what is always a difficult and contentious issue for the USFS to address. This is again proven true on the Magdalena as the overwhelming basis for public comment on the draft was the closure of routes. While the vast amount of public comment was related to limiting closures of routes, the Proposal failed to address many basic flaws in the draft EA on the underlying research, such as failing to fully explore current management, failing to provide a full range of alternatives on contested issues and failing to meaningfully address economic impacts from the Proposal.

TPA submits that given this overwhelming public input seeking to maintain current levels of multiple use access to the area, which is consistent with credible input from a wide range of partners, there is clearly unresolved conflicts about alternative uses of available resources. This conflict mandates a full, complete and meaningful review of these issues as a matter of law under NEPA.

TPA submits that two alternatives are available that satisfy the purpose and need of the proposal and do not close 40% of the routes in the planning area. The first alternative that is available and never addressed is simply recognizing the existing routes in the area and placing them on an MVUM. As the purpose and need is clearly identified as the need for the Magdalena RD to comply with the Travel Management Rule, this alternative has frequently been used by the USFS to achieve this goal. TPA submits that many ranger districts facing budget issues frequently identify existing routes in the district on their MVUM and simply do not close any routes. This decision has been frequently litigated and the USFS has been highly successful in defending these decisions. The second alternative that was simply never addressed would be the determination that existing roads could be designated as trails and allowed to remain open for access to recreational opportunities, as the Mount Taylor Ranger District of the Cibola NF recently determined was a viable means to achieve the goals and objectives of the Proposal. TPA would note that the purpose and need of the Mount Taylor project and the Proposal are almost exactly the same, and as a result this management clearly represents an alternative that was not explored. TPA submits this comparison is highly relevant as the Mount Taylor Ranger District is immediately adjacent to the Magdalena District in the Cibola NF. Why the alteration of roads to the lower trail level of classification was not explored remains unresolved and entirely unclear in the final EA and related documents. TPA vigorously submits that the analysis provided to date artificially limits the scope of alternatives provided in violation of NEPA.

Agency determinations regarding the need for closures of approximately 40% of the routes in the planning area are never analyzed or reviewed and fall well outside alternatives which could fulfill the purpose and need of the project. TPA submits there are clearly two management options to comply with the TMR, additional analysis must be provided to address the need to close an additional 40% of routes in the planning area as is the preferred alternative of the Proposal. After an extensive review of the EA, this analysis simply cannot be located as no reasons for closures, such as resource impacts, Endangered Species concerns or limited USFS budgets are even mentioned.

TPA submits that development of all alternatives for usage of current resources simply has not occurred and has compounded failures to meaningfully address the economic impacts to local communities from the Proposal. Rather than meaningfully preparing an EA, the complete lack of information on economic impacts from altered recreational usage is noted and the EA simply moves forward. TPA submits this falls well short of the hard look at issues required by NEPA.

The only non-recreational economic activity that is identified in the Proposal as possibly being impacted by the Proposal is firewood gathering. This position simply lacks any factual basis as USFS documentation identifies that firewood gathering is 17th on the list of reasons people visit the planning area. TPA vigorously asserts that motorized access plays a critical role in the other 16 activities higher on the list of reasons people visit the area, and no reason is given for why possible impacts to these 16 other activities are not addressed.

Each of these issues is a per se violation of NEPA requirements and relevant court decisions and mandate the Proposal be overturned and returned to the district in order for an accurate economic analysis to be performed and all alternatives be meaningfully explored and those that are not pursued are clearly discussed with the public in any supplemental documentation that might be provided. Please feel free to contact Scott Jones at 518-281-5810 or by mail at 508 Ashford Drive, Longmont, CO 80504 for copies of any documentation that is relied on in this appeal or if you should wish to discuss any of the concerns raised further.

Respectfully Submitted,

Scott Jones, Esq.

TPA Authorized Representative

Don Riggle

Director of Operations

Trails Preservation Alliance

1 See, Pub. L. No. 111-5, § 3, 123 Stat. 115, 115-116 (2009).

2 See, 40 CFR 1508.9

3 See, 42 USC 4332 (2)(E)

4 See, City of New York v. DOT, 715 F.2d 732 (2d Cir. 1983) at pg 741

5 See, Hughes River Watershed Conservancy v. Glickman; (4th Circ 1996) 81 F3d 437 at pg 442; 42 ERC 1594, 26 Envtl. L. Rep 21276.

6 See, Hughes River Supra note 2 at pg .

7 See, Hughes River, Supra note 2 at pg

8 See, Magdalena Travel Plan Socio-Economic Specialist Report (July 3, 2013) at pg 30.

9 See, Baltimore G& E Co v. NRDC; 462 US 87 (1983) at pg 98.

10 See, 40 CFR 1500.1(b)

11 See, Allen et al; Does not provide a range of alternatives to satisfy NEPA…..NEPA Alternatives Analysis: The Evolving Exclusion of Remote and Speculative Alternatives; 2005 25 J. Land Resources & Envtl. L. 287.

12 See, Citizens for a Better Henderson v. Hodel, 768 F. 2d 1051, 1057 (9th Cir. 1985).

13 See, Kunzman, 817 F. 2d at 492; see also Citizens for a Better Henderson, 768 F. 2d at 1056.

14 See, 40 CFR §1508.9 and 42 USC §4332(2)(E).

15 See, USFS- Mount Taylor Ranger District of the Cibola NF- August 2010 at pg 5.

16 See, USFS Magdalena RD travel Plan at pg 5.

17 See, Magdalena Travel Plan Socio-Economic Specialist Report (July 3, 2013) at pg 30.

18 See, Western Governors Association; Get Out West Report; Managing the Regions Recreational Assets; June 2012 at pg 3. Hereinafter referred to as the “Get Out West” report.

19 See, Get Out West Report at pg 5.

20 See, USDA Forest Service – Office of Rural Development; Dr. Glenda Humiston; Jobs, Economic Development and Sustainable Communities Strategizing Policy Needs and Program Delivery for Rural California; Feb 2010 at pg 48

21 pg 1.

22 See, USFS Magdalena Ranger District – Recreation and Scenic Resource Specialist Report – Magadalena Ranger District Travel Management Project; at pg 1.

23 See, USFS National Visitor Use Data: Round 2 report for the Ciobla National Forest at pg 21.

24 See, NVUM report pg 22

25 See; White and Stynes; Updated Spending Profiles for National Forest Recreation Visitors by Activity; Nov 2010 at pg 6.

26 See, Magdalena Travel Plan Socio-Economic Specialist Report (July 3, 2013) at pg 30.

27 See, Magdalena Travel Plan Socio-Economic Specialist Report (July 3, 2013) pg 12.

28 See, Outdoor Industry Association, The Outdoor Recreation Economy; New Mexico Report 2012 – full copy of this report is available here. https://outdoorindustry.org/images/ore_reports/NM-newmexico-outdoorrecreationeconomy-oia.pdf

29 See, USFS ; Off-Highway Vehicle Recreation in the United States and its Regions and States: An Update National Report from the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment (NSRE) This is a RECSTATS Research Report in the IRIS Series1 February, 2008 at pg 22.

30 See, New Mexico SCORP 2010-2014 at pg 23.

31 See, National Shooting Sports Foundation; 2011; Issues relate to hunting access in the United States: Final Report; Accessed December 4, 2013; http://www.nssf.org/PDF/research/HuntingAccessReport2011.pdf at pg 7. (hereinafter referred to as “NSSF report”)

32 See, NSSF Report at pg 3-4.

33 See, NSSF report at pg 56.

34 See, NSSF report at pg 113.

35 See, Roggenbuck and Watson; Wilderness Recreation Use; The Current Situation; INT 4901 #191.

36 Roggenbuck and Watson; at pg 347.

37 Roggenbuck and Watson; at pg 353.

38 Roggenbuck and Watson; at pg 354.